Coastdat.eu

Final Draft

of the original manuscript:

Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Almasy, L.; Garamus, V.M.; Zou, A.;

Willumeit, R.; Fan, S.:

Preparation and characterization of 4-dedimethylamino

sancycline (CMT-3) loaded nanostructured lipid carrier

(CMT-3/NLC) formulations

In: International Journal of Pharmaceutics (2013) Elsevier

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.021

Preparation and characterization of 4-dedimethylamino sancycline

(CMT-3) loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (CMT-3/NLC)

Xiaomin Yang1a Lin Zhao1c Laszlo Almasyd Vasil M. Garamusb Aihua Zoua Regine Willumeitb Saijun Fanc

State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering and Institute of Applied Chemistry, East China University of

Science and Technology, Shanghai 200237, PR China,

Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht: Centre for Materials and Coast Research, Institute of Materials Research,

Max-Planck-Str. 1, D-21502 Geesthacht, Germany

School of Radiation Medicine and Protection, Soochow University Medical College, Suzhou 215123, PR

Research Institute for Solid State Physics and Optics, HAS, Konkoly-Thege Miklós út 29-33, 1525 Budapest,

* To whom correspondence should be addressed. Tel/Fax.: +86-21-64252063.

E-mail:

[email protected].

East China University of Science and Technology.

Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht.

Soochow University Medical College

Abstract

Chemical modified tetracyclines (CMTs) have been reported to have strong

inhibition ability on proliferation and invasion of various cancers, but its application is

restricted for its poor water solubility. In present study, hydrophilic CMT-3 loaded

nanostructured lipid carrier (CMT/NLC) was produced by high pressure

homogenization (HPH). The physical properties of CMT/NLC were characterized by

dynamic light scattering (DLS), high efficiency liquid chromatography (HPLC),

atomic force microscopy (AFM), Scan electron microscopy (SEM), Small-Angle

Neutron Scattering (SANS), small angle and wide angle X-ray scattering (SAXS and

XRD) The lipids and surfactants ingredients, as well as drug/lipids (m/m) were

investigated for stable and sustained NLC formulations. In vitro cytotoxicity of

CMT/NLC was evaluated by MTT assay against HeLa cells. The diameter of

CMT/NLC increased from 153.1±3.0 nm to maximum of 168.5±2.0 nm after 30 days

of storage while the entrapment efficiency kept constant at >90 %. CMT/NLC

demonstrated burst-sustained release profile in release mediums with different pH,

and the 3-dimension structure of CMT/NLC was suspected to attribute this release

pattern. The results of cell uptaking and location indicated that NLC could arrive at

cytoplasm and NLC makes CMT-3 entering HeLa cells easier. All results showed that

NLC was important to CMT-3 application not only in lab research but also in clinical

field. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report on CMT/NLC.

Key words: Nanostructured lipid carriers; CMT-3; SANS&SAXS; XRD; in-vitro

release; cytotoxicity

1. Introduction

Chemically modified tetracyclines (CMTs) are analogs of tetracycline (Fig 1),

which is used clinically as an antibiotic agent. Golub and co-workers first investigated

and described that CMTs lack antimicrobial properties but still inhibit matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Golub et al., 1991). Since then, numerous in vivo and in

vitro studies have demonstrated that CMT-3, also known as COL-3, is the most

promising anti-tumor molecular compared to other CMTs (Lokeshwar et al., 2002).

CMT-3 has been shown to have strong inhibition ability on proliferation and invasion of

various cancer, such as E-10, MDA-MB-468 human breast cancer cells, COLO 205

colon carcinoma cells, and DU-145, TSU-PR1, and Dunning MAT LyLu human

prostate cancer cells (Gu et al., 2001; Lokeshwa, 1999; Lokeshwa et al., 1998;

Lokeshwar et al, 2001; Lokeshwar et al, 2002; Meng et al., 2000). The anti-metastatic

effect of CMT-3 also has been assessed in the bone metastasis model of MAT LyLu

human prostate cancer cells in rats and the lung metastasis model of C8161 human

melanoma cells in SCID mice (Seftor et al., 1998; Selzer et al., 1999). Though CMT-3

had significant effect on inhibiting tumor metastasis and had several potential

advantages over conventional tetracyclines, the adverse effects included nausea,

vomiting, liver function tests abnormalities, diarrhea, mucositis, leukopenia, and

thrombocytopenia were observed in clinical trials (Syed et al., 2004). The main reason

may attribute to CMT-3's hydrophobic and lipophilic ability, which make it

concentrate in high fatty tissue and produce toxic effects. Because of the poor

water-solubility, the drug is hard to be absorbed into human blood and interstitial fluid,

and it is difficult to be transported into the target human body or abnormal tissue and

organ effectively. On the other hand, because CMT-3 can't be dissolved totally in

saline, the injection manner of giving drug may be forbidden in clinical usage. So, the

improvement of CMT-3 water-solubility has great importance in its clinic application.

Fig 1. The structures of doxycycline (upper) and CMT-3 (lower).

Over the past several decades, much interest has focused on the design of more

efficient drug delivery systems to address problems such as low drug solubility. The

particulate delivery systems address a number of characteristics including appropriate

size distribution, high drug loading, prolonged release, low cellular cytotoxicity and

cellular targeting. The nanostructured lipid carrier was first developed by Prof. Rainer

H. Müller during the late 1990s (Eliana et al., 2010). NLC is composed of mixture of

solid and liquid lipid compounds such as triacylglycerols, fatty acids, steroids, and oil

(Rainer et al., 2007). NLC is attractive for its combination of advantages of many

other drug carriers (solid lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, liposomes and

emulsions) (Rainer et al., 2004). NLC can be produced on a large scale using lipids

and surfactants that are already accepted, and long-term stability NLC formulations

have been reported for various applications (Khalil et al., 2011; Medha et al., 2009).

NLC can enhance lipophilic drug solubility by virtue of its lipids core and aqueous

shell. Enhances solubility is significant because a great number of drug candidates are

poorly soluble. Also, the solid matrix provides NLC with sustained release properties,

as the degradation or erosion of the lipid matrix releases the incorporated drugs from

NLC. Finally, the nanosize of NLC increases its therapeutic efficacy and reduces

toxicity. In this study, CMT-3 was incorporated into a NLC made up of biodegradable

and biocompatible fatty acids and triacylglycerols. The aim of this study was to

design long-term stable water soluble CMT/NLC formulations with proper size, high

drug loading and sustained release profiles. Cellular uptake and cellular location were

investigated using rhodamine B as a probe for these high efficiency antitumor

formulations. To our knowledge, this is the first repot on CMT/NLC, and there has no

evidence showing CMT-3 loaded other nanoformulations so far. The results in this

study imply that this CMT-3 loaded nanocarrier may significantly improve the

effectiveness of CMT-3 in clinical applications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

4-dedimethylamino sancycline (CMT-3, CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals Inc,

Newtown, Pennsylvania); Steric acid (SA, LingFeng Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd,

China ); monoglyceride (MGE, Aladdin Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd, China ); oleic

acid (OA, Aladdin Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd, China); capric/caprylic triglycerides

(MCT, Aladdin Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd, China); Cremophor EL(Aladdin Chemical

Reagent Co. Ltd, China); Pluronic F68 (Adamas Reagent Co. Ltd, China); freshly

prepared double distilled and ultra purified water; trehalose (Aladdin Chemical

Reagent Co. Ltd, China); 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium

bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), D2O (Sigma, Germany).

2.2. Preparation, particle sizes and size distribution of NLCs

NLC were prepared by high pressure homogenizer (HPH). In brief, aqueous

phase which consisted of double distilled water and one or two surfactants

mixture(1/1, m/m) and oil phases (lipid mixtures, including SA, MGE, OA and MCT)

were separately prepared. Desired oil phase were maintained at 70 °C to prevent the

recrystallization of lipids during the process, then CMT-3 was added to the oil phase

which was stirred until completely dissolved. The same temperature aqueous phase

was added to the oil phase with intense stirring (10000 rmp for 1 min; Turrax T25,

Fluko, Germany). These dispersions were processed through an HPH (ATS

Engineering, Canada) with five homogenization cycles at 600 bar. The

nanodispersions were cooled overnight at room temperature to obtain the

nanostructure lipid carrier.

All samples were lyophilized for long stability. Appropriate amounts of trehalose

(3% w/v in water) were used to dilute the NLC dispersions. The samples were frozen

at -78 °C for 10 h before being lyophilized for 36 h. The freeze-dried powders were

rehydrated with phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4) for later experiments.

The mean particle size and polydispersity of NLCs were measured by dynamic

light scattering at 25 °C using Nano-ZS90 system (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK)

with a measurement angle of 90 °.

2.3. Entrapment efficiency (EE) and drug loading (DL)

To determine the amount of CMT-3, methanol was added to CMT/NLC

formulations to destroy the NLC structure and dissolve the CMT-3 that was released.

The content of CMT-3 was determined by HPLC (Wufeng, China) using the following

experiment conditions: Diamond C18 column (150 nm×4.6 nm i.d, pore size 5µm; A

yi te, China), the mobile phase MeOH: H2O (0.5% TFA, v/v) = 30:70 (v/v), flow rate:

1 mL/min, and wavelength: 360 nm. The calibration curve of CMT-3 concentration

against peak area was C=8.86793*10-7A+0.00248 (R2=0.9999). All the experiments

were conducted at room temperature (25 °C). The drug loading (DL%) and

entrapment efficiency (EE%) were calculated by the following formulas:

DL% = the weight of CMT-3 encapsulated in the NLC / the total weight of CMT/NLC

EE% = the calculated DL / the theoretical DL ×100.

2.4. NLC morphology study

The surface morphology of NLCs was examined by Nanofirst-3100 AFM

(Suzhou Hai Zi Si Nanotechnology Ltd, China). Samples for AFM were prepared by

placing a drop of freshly prepared unloaded blank-NLC and CMT/NLC on the mica

sheet and drying by spin coating.

Scan electron microscopy (SEM, Auriga 40, Zeiss, Germany) was used to study

the internal structures of blank-NLC and CMT/NLC. Before scanning, the samples

were placed on the conductive double-sided sticky tape and then coated with gold in

an argron atmosphere.

2.5. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering

SANS measurements were performed on the Yellow Submarine instrument at the

BNC in Budapest (Hungary) (Rosta L, 2002). The overall q-range was from 0.03 to 1

nm-1. The samples were filled in Hellma quartz cells of 2 mm path length and placed

in a thermostated holder kept at 20.0±0.5 °C. The raw scattering patterns were

corrected for sample transmission, room background, and sample cell scattering. The

2-dimensional scattering patterns were azimuthally averaged, converted to an absolute

scale and corrected for detector efficiency dividing by the incoherent scattering

spectra of 1 mm thick pure water. The scattering from PBS buffer prepared in D2O

was subtracted as the background. Fourier Transformation (IFT) was applied in this

study to analyse the scattering pattern.

2.6.

Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering

The SAXS measurements were performed at laboratory SAXS instrument

(Nanostar, Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). Instrument includes IμS

micro-focus X-ray source with power of 30 W (used wavelength Cu Kα) and

VÅNTEC-2000 detector (14×14 cm2 and 2048×2048 pixels). Sample to detector

distance is 108.3 cm and accessible q range from 0.1 to 2.3 nm-1.

2.7. Wide-Angle X-ray powder diffraction

The crystalline structure of CMT-3, unloaded blank-NLC and CMT/NLC were

investigated by D/MAX 2550 VB/PC X-ray diffractometry (Rigaku, Japan). Aqueous

blank-NLC and CMT/NLC were lyophilized before the XRD measurement.

Diffractograms were obtained from the initial angle 2 θ = 10 ° to the final angle 60 °

with a Cu Kα radiation source. The obtained data were collected with a step width of

0.02 ° and a count time of 1 s.

2.8. In vitro release of CMT-3

The in vitro release of CMT-3 from CMT/NLC was conducted by dialysis bag

diffusion (Xu et al., 2009). 5 mL fresh prepared CMT/NLC solution (100 μg/ml) was

placed into a pre-swelled dialysis bag with 7 KDa MW cutoff. The dialysis bag was

incubated in release medium (PBS, pH 7.4 VS pH 5.5; 20 mL) with 0.5 % of Tween

80 to enhance the solubility of released free CMT-3 and to avoid its aggregation at

37 ℃ under horizontal shaking. At predetermined time points, the dialysis bag was

taken out and placed into a new container containing fresh release medium (20 mL).

The content of CMT-3 in release medium was determined by HPLC as described by

section 2.3. The release rates of CMT-3 were expressed as the mass of CMT-3 in

release medium divided by time.

2.9. Cell morphology

HeLa cells were seeded in 6-well plate after 0.25 % trypsin digestion at a density

of 3×106 per well. After 12 h, cells were exposed to 20 μM CMT-3, blank-NLC and

CMT/NLC for 6 h. The cell morphology was captured by digital camera (Olympus).

2.10. Cell culture

The human cervical cancer cell line HeLa was purchased from American Type

Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were seeded into cell culture

dishes containing DMEM supplemented with 10 % new calf serum,

L-glutamine (5

mmol/L), non-essential amino acids (5 mmol/L), penicillin (100 U/mL), and

streptomycin (100 U/mL) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), at 37 °C in a humidified

5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.11. In vitro cellular cytotoxicity assays

Cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dipheny

ltetrazoliumbromide (MTT) assay. HeLa cells were plated in 96-well plates with 100

μL medium at a density of 8×103 per well. After 12 h, cells were exposed to various

concentrations of CMT-3, blank-NLC and CMT/NLC for 24 and 48 h. MTT solution

was directly added to the media in each well, with a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL

and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The formazan crystals were solubilized with 150 μL

DMSO. The absorbance was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

reader at 570 nm, with the absorbance at 630 nm as the background correction. The

effect on cell proliferation was expressed as the percent cell viability. Untreated cells

were taken as 100 % viable.

2.12. Cellular uptake of NLC formulations

Rhodamine B (RB, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was used as probe to study the

uptake and location of NLC in Hela cells. RB was encapsulated in NLC, and the free

RB was removed via dialysis bag (MW 7000). HeLa cells were seeded in Lab Tek

chamber slides (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) at the density of 2×104 and incubated

for 24 h. The real-time subcellular localization was determined using Cell'R Live Cell

Station (Olympus Company, Inc). The images were captured every 30 second and last

for 15 min. RB/NLC was added at equivalent rhodamine B immediately after the first

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation, particle sizes and distribution of NLCs

In this study, monoglyceride and stearic acid (solid lipids) and oleic acid and

capric/caprylic triglycerides (liquid lipids) were selected for their high ability to

dissolve CMT-3. The non-toxic, non-ionic surfactants, Cremophor EL and Pluronic

F68 were used to increase the stability of NLC.

Many methods have been reported for NLC preparation, including hot and cool

homogenization (Liu et al., 2010), microemulsion (Soheila et al., 2010),

ultrasonication (Wang et al., 2009), solvent emulsion and phase inversion. Among

these, hot homogenization and solvent emulsion have been widely applied, and given

the point that CMT-3 is easily dissolved in organic solvent, high pressure

homogenization (HPH) was used to prepare CMT/NLC for high entrapment

Table 1. Effects of lipid ingredients on mean particle size of blank-NLC.

Mean particle PDI*

Lmix-1 1113 557 415 415 190±3.2 0.30

Lmix-2 1113 557 593 237 150±5.0 0.14

Lmix-3 1074 596 553 277 148±1.9 0.15

Lmix-4 1074 596 593 237 138±4.2 0.20

SA (stearic acid) is a saturated fatty acid with an 18 carbon-chain length, and a

highly lipophilic character. It is often used as solid lipid for the production of NLC.

The selection of MCT as liquid lipid was for its thermodynamic stability, and high

solubility for many drugs (Patricia et al., 2011). In addition, its less ordered structure

is better for imperfect NLC, which is critical for high EE and DL. In fact, as indicated

in Table.1, formulas (Lmix-2 VS Lmix-1, and Lmix-4 VS Lmix-3) with high MCT

showed smaller sizes and more uniform dispersion, while the incorporation of OA

increased the particle size and PDI. This was mainly because the melting point of OA

is low and therefore OA increases the mobility of the internal lipids and fluidity of the

surfactant layer (Radheshyam and Kamla, 2011). Consequently, the ratios between

lipids were fixed as MGE/SA = 2/1, and CMT/OA = 2/1 (m/m).

Table 2. Effects of the concentration of surfactants on mean particle size and stability.

Total surfactant

Mean particle size (nm)

concentration (%)

The studies of surfactants are of great importance for the development of stable

NLC formulas. In addition, while moving through the vasculature, NLC interacted

with various components of blood. The hydrophilic of NLC avoid protein adsorption

on the surface and hence induce delayed immune clearance (Yoo. et al., 2011).

Cremophor EL is FDA approved, and already clinically used for intravenous injection.

In addition, F68 was chosen for its long PEG chains, and PEG chains are known for

providing a stealth character to nanocarriers and slow their elimination from the

bloodstream during intravenous injection (Delmas et al., 2010).

According to pre-experiments (surface tension studies, data are not shown) the

ratio between Cremophor EL and F68 was fixed as 1:1. The total surfactant

concentration was also studied. As can be seen from Table 2, the concentration of

surfactants had only slight effects on mean particle size, whereas increasing

concentrations of surfactant had significant influence on the stability of the dispersion.

This could be explained by the fact that high amount of surfactant make the oil phase

disperse more readily into aqueous phase. Also, the new lipid surface presented during

the HPH process was covered by high concentrations of surfactant, thereby providing

higher homogenization efficiency. Too much surfactant, however, lowered the

stability of NLC. Many factors may have contributed to this phenomenon. For

example, the long PEG chains of F68 can interact with each other by hydrogen

bonding, and surfactants may form large size micelles.

3.2. Entrapment efficiency and drug loading

Not only the stability, but also entrapment efficiency and drug loading are vital

for clinical application of CMT/NLC. In section 3.1, the type and concentration of

lipid ingredients and surfactants were investigated for stable and small size NLC

formulas, in this section the effects of the ratio between drug and lipids on entrapment

efficiency and drug loading was studied.

Table 3. The effects of lipids and CMT-3 content on mean particle size. Values are

mean ± SD (n=3)

Experiments Lipid CMT-3

Mean particle size Mean particle size

38.5 140.0±3.2 145.7±4.9

60.5 145.8±4.9 154.5±5.0

100.0 145.2±5.0 200.0±3.5

100.0 153.1±3.0 168.5±2.0

200.0 142.4±5.1 200.0±4.5

Fig 2. The effects of lipids and CMT-3 concentration on entrapment efficiency and

drug loading. *The labels of samples are the same as in Table. 3. Values are mean ±

The details of CMT/NLC formulas were shown in Table 3, and the mean particle

sizes were measured during 30 days. It was clear that the particle sizes of all formulas

were <200 nm during the storage period. Fig 2 illustrates that the amount of lipids

and CMT-3, and the storage time, had direct relationships with the entrapment

efficiency and drug loading. For the first day after preparation, the entrapment

efficiency and drug loading values of these CMT/NLC formulations (experiments 1 –

5) were in the range of 90 - 96 % and 4.2 - 10.6 %, respectively. It can be concluded

from the data for experiments 1, 2 and 3, that higher drug/lipid ratios didn't increase

the entrapment efficiency. When the amount of CMT-3 is close to its saturation

solubility in the lipid phase, cooling the nanoparticles leads to supersaturation of

CMT-3 in the liquid lipids and consequently to CMT-3 precipitation prior to lipid

precipitation, and therefore to lower entrapment efficiency (Sylvia and Rainer., 2004).

The entrapment efficiency of experiment 4 was higher than that of experiment 3; this

can be explained by the fact that high amounts of lipids increase the solubility of

CMT-3. According to the results from Table 3 and Fig 2, the experiment 4 was chosen

for further studied.

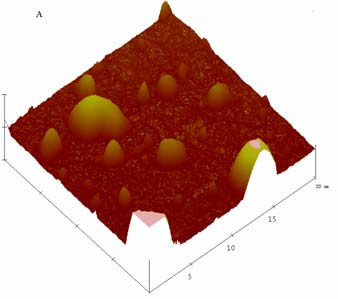

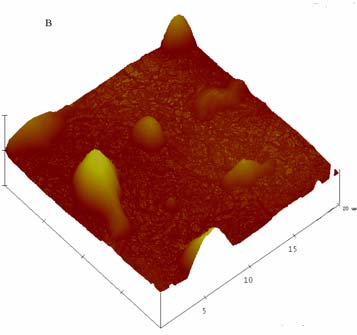

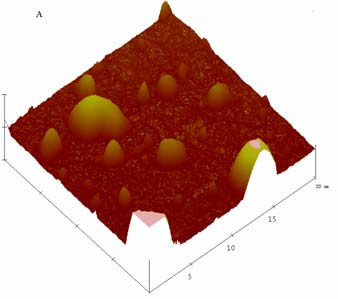

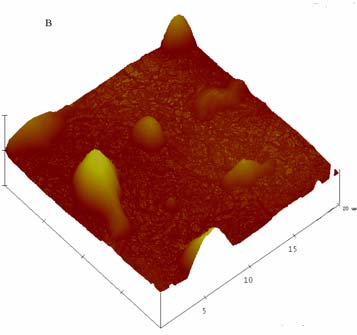

3.3. NLC morphology study

Given that the shape of NLC may affect important biological processes,

including biodistribution and cellular uptake, in drug delivery application

(Venkateraman et al., 2011), AFM was used to investigate the non-hydrated state of

NLCs. It can be seen from Fig 3 that both blank-NLC and CMT/NLC had irregular

morphology with smooth surface. Many factors may induce irregular morphology, for

example, i) the powerful mechanical force and shearing force during preparation, ii)

liquid lipids increase the mobility of lipid phase. But larger particles may result from

the NLC aggregation during spin coating.

Fig 3. AFM images of blank-NLC (A), and CMT/NLC (B).

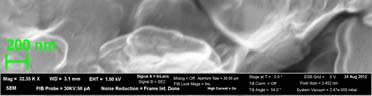

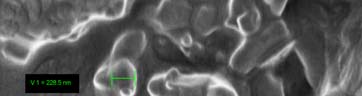

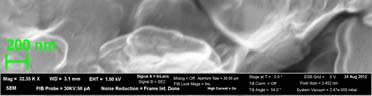

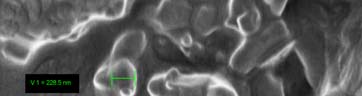

Fig 4 demonstrated the SEM results of unloaded NLC and CMT loaded NLC

after freeze-drying. Both the blank-NLC and CMT/NLC were located in the bulk and

grid structure formed by trehalose. The diameters of from SEM were larger than those

measured by DLS because of the coating before measurement. In addition, the shape

of unloaded NLC was almost spherical, but CMT/NLC was elongated. It was reported

that the elongated, flexible core-shell structures have demonstrated unique

visco-elastic and rheological properties (Ezrahi et. al., 2007; Dreiss, 2007) and the

importance of elongated particles in drug delivery applications has been realized with

the advent of pioneering works of Discher's lab (Geng et. al., 2007; Geng and Discher,

Fig 4. The SEM photographs of blank-NLC (A) and CMT loaded NLC (B).

3.4. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering

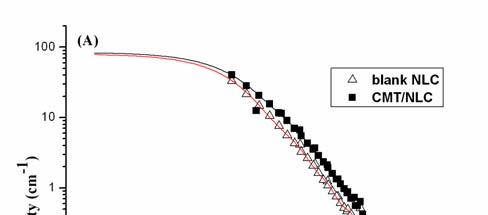

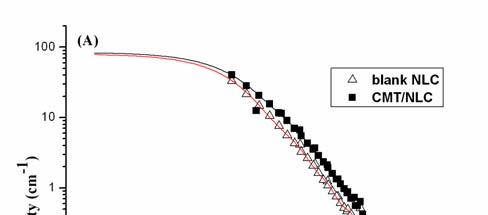

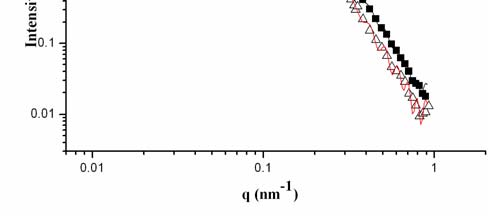

Fig 5. SANS spectra of NLC before and after loaded with CMT-3 in PBS (A); P(r)

function obtained from the corresponding scattering curves in A.

SANS was used to study the effect of CMT-3 on the NLC structure. Indirect

fourier transformation (IFT) method was applied in this study. This

model-independent approach needs only minor additional (model) information on the

possible aggregate structure (Glatter., 1977). The experimental data and the fitted

curve coincide very well for both blank NLC and CMT/NLC for all q ranges (Fig

The possible shape and diameter can be obtained from the pair distance

distribution p(r) function (Fig 5B). Blank NLC displayed almost spherical structure

(maximum of p(r) function is located near the middle of maximal size), while after

adding CMT-3 the maximum of p(r) moves to smaller r and it could be interpreted

that the shape became elongated. In fact, this result is agreement with that of SEM.

The particle size (mean diameter) obtained from Fig 5B was significantly smaller than

the data got from DLS. There were two reasons for this disagreement: i) due to

limited qmin SANS data point only on low limit of maximal size of aggregate, ii) DLS

observes hydrated size of particles (particles plus hydrated water) and SANS points to

It is important to obtain the direct information about the structure change from the

large q part of SANS measurements. At a q range, an evidence for fractals in the

submicrometer and nanometer scale can be conveniently derived from small-angle

scattering based on well-known dimensional analysis (Schmidt, 1995). The power law

of the scattering intensity I(q) can be described as I(q) q-α. This exponent indicates the

microscopic structure of scatter can be understood as mass fractals or surface fractals.

When the angular coefficient of the log I(q) versus log q plot is determined, its

relationship with the dimensions of mass and surface fractal, Dv and Ds is α=2×Dv-Ds.

In this study, the α values for blank NLC and CMT/NLC were 3.55 and 3.7,

respectively. It means that such particles have a dense core and rough surface, the core

has a Euclidean dimension, Dv=3, whereas the surface obey a relation Ds=6-α.

Decreasing of value of surface fractal dimension from 2.45 to 2.3 by adding drug to

NLC points on changes of surface of NLC which become smoother. It was in

qualitative agreement with SEM.

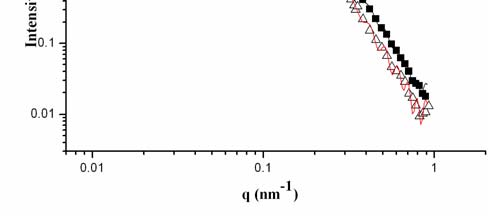

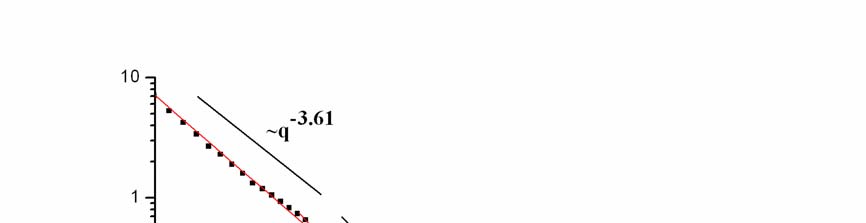

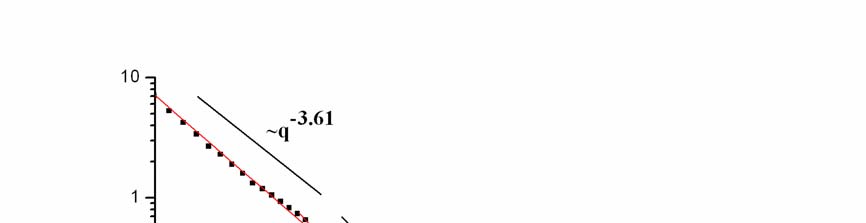

3.5. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering

Fig 6. SAXS curve for film freeze-dried blank-NLC and CMT/NLC at 25 °C.

The three-dimensional structures of freeze-dried CMT/NLC and blank NLC were

studied by SAXS. The evaluation of the X-ray spectra was got as reported before

(Seydel et al., 1989; Mariani et al., 1993). There are two peaks (Fig 6, q = 1.31 nm-1,

1.61 nm-1), which means that CMT/NLC is cubic in 3-dimensional structures

(Brandenburg et al., 1998). In fact, blank NLC had the same structures, thus the

adding of CMT-3 did not change the 3-dimensional structures. Low q part of SAXS

has been analyzed by dimensional analysis similar to SANS data obtained for solution

of NLC. Slope of I(q) vs q points to surface fractal structure and corresponds to

surface fractal dimension 2.39 similar to NLC in solution. For blank NLC, the slope

varied from 3.71 to 3.88 at q=0.48 nm-1(curve is not shown), which was coincided

with the rough surface that got from SANS. In the case of CMT/NLC we have also

observed crossover from slope of 3.61 to 4 (smooth surface) at q=0.43 nm-1 which

points on size of primary smooth aggregates forming fractal cluster around 2 nm.

3.6. Wide-Angle X-ray powder diffraction

Fig 7. X-ray diffraction analysis of CMT-3 formulations: X-ray powder

diffractograms of CMT-3 (A), freeze-dried unloaded blank-NLC (B) and freeze-dried

XRD was used to study changes of the microstructure in NLC. XRD analysis

makes it possible to assess the length of the long and short spacing of the lipid lattice.

In Fig 7, the intensities of several diffraction peaks characteristic of CMT-3 reduced in

freeze-dried CMT/NLC, and the diffraction intensity of CMT/NLC was clearly

stronger than that of unloaded blank-NLC. This phenomenon could be attributed to

crystal changes. Many factors can result in changes of crystal structure, for example,

the amount and state of CMT-3 in NLC (Veerawat et al., 2008). Also, the differences

in intensity between blank-NLC and CMT/NLC may be due to the less ordered

microstructure of blank-NLC in comparison to that of CMT/NLC (Lopes et al., 2012).

Thus, adding CMT-3 to imperfect NLC increases crystallinity of CMT/NLC.

3.7. In vitro release of CMT-3

The release experiment was conducted under sink conditions and the dynamic

dialysis was used to separate the CMT-3 that released from CMT/NLC. Fig 8

demonstrated the influence of pH on release profiles of CMT/NLC and release rate of

CMT-3 from CMT/NLC in PBS (0.5 % of Tween 80 in PBS, pH 7.4). It was

obviously that about 58 % CMT-3 released from NLC in PBS (pH 5.6), while for PBS

(pH 7.4) there was about 68 % CMT-3 released from NLC. Thus acidity seemed good

for prolonged release, and CMT-3 had burst release in both medium. But in the

following hours, CMT-3 showed prolonged release profiles. As for release rate (Fig

8B), the release rate of CMT-3 in PBS (pH 7.4) decreased sharply in the first 3 hours,

but after the first 3 hours, the release rate was almost constant (0.02 mg/h) in the

following 45 hours. Thus in both release medium, CMT/NLC exhibited a

burst-prolonged release profile. The solid matrix of NLC and location of CMT-3 in

NLC might attribute to this release pattern. It was reported that the drug can be

incorporated between fatty acid chains, between lipid layers or in imperfections

(Sylvia and Rainer., 2004). During the cooling process, solid lipids (SA and MGE)

rapidly solidified to form solid lipid core for their high melting points, and the rest

liquid lipids distributed randomly around solid lipid core. As liquid lipids had higher

solubility of drug, large amount of drug were loaded in outer lipid layer. In

vitro-release experiment, in the burst release stage, CMT-3 that loaded in shell

released easily and rapidly, while in the sustained release stage, the CMT-3 that

loaded in solid lipid core released by matrix erosion and degradation of lipid

components of NLC, which resulted in prolonged release manner. In addition, the

cubic structure of CMT/NLC protected CMT-3 from leaking from NLC, Other factors

contributing to the fast release are the large surface area, high diffusion coefficient of

nanoparticles, the low viscosity, and short diffusion coefficient of CMT-3 and

surfactant concentration (Zhigaltsev et al., 2010).

Time (hour)

Time (hour)

Fig 8. The in-vitro release study. Cumulative release of CMT-3 in different release

mediums: pH7.4 (A), and pH5.6 (B). Values are mean ± SD (n=3).

3.8. In vitro cellular cytotoxicity assays

In order to know the biological activity of CMT-3 loaded nanoparticles

(CMT/NLC), the cellular cytotoxicity was evaluated by MTT assay. As Fig 9 shows,

CMT-3 exhibits great inhibition effect on Hela cells growth in the given concentration.

For example, the viability of HeLa cells treated with 20 μM CMT-3 for 24 h or 48 h

was 70.9±7.5 % and 61.1±4.4 %, respectively. When treated with 20 μM CMT-3 for

24h, CMT/NLC had more inhibitory ability than CMT-3 (t=3.02, P<0.05, Fig 9A).

Compared to CMT-3, the inhibition effects of CMT/NLC was also remarkably greater

over concentration ranging from 2 to 20 μM when treated for 48 h (t=6.00, 4.40, 4.49,

25.55, P<0.01, Fig 9B), which means the sustained release properties of CMT/NLC

for its cubic structure. It should be pointed out that blank-NLC did not have any

obvious cytotoxicity on HeLa cells, even in high concentration and 48 h exposures.

Fig 9. In vitro cytotoxicity of CMT-3 and CMT/NLC against HeLa cells for 24 h (A)

or 48 h (B). Cell viability is expressed as the percentage of untreated controls. Data

are given as mean±SD (n=6). *p < 0.05 compared with CMT-3.

3.9. Cell morphology

In order to compare the morphology changes of HeLa cells treated with CMT

and CMT/NLC, we used the microscope and digital camera to observe the differences

between the groups. 20 μM CMT-3 exhibits no obvious effect to HeLa cells'

morphology for 6 h (Fig 10B), and the same phenomenon was observed when cells

were treated with blank-NLC (Fig 10C), the volume of which was the same as

CMT/NLC. But, CMT/NLC make cells' morphology changes a lot. As Fig 10D shows,

cell condensation and fragmentation as well as cell shrinkage were observed. The

results indicated that CMT/NLC was easier in leading to cells' toxicity compared to

CMT-3 at the same concentration.

Fig 10. HeLa cells were treated with different medium for 6 h: A. control, without any

treatment; B. 20 μM CMT-3; C. blank-NLC (same volume with CMT/NLC); D.

CMT/NLC (CMT concentration is 20 μM). Cells were captured by digital camera

3.10. Cellular uptake of NLC formulations

We observed the changes of HeLa cells' morphology after treated with RB/NLC.

After HeLa cells were exposed to RB/NLC for 2 h (Fig 11 row 1B shows), it was

clearly that some white pellets appeared around the cells, it was assumed to be

RB/NLC. The control group without CMT/NLC treatment (Fig 11 row 1A shows) has

no this phenomenon.

In order to observe the intracellular distribution of NLC, Cell'R Live Cell Station

was used to capture Hela cells after treatment with RB/NLC every 30 second. As time

went on, the intensity of fluorescence was increasing in cytoplasm in HeLa cell. As

shown in Fig 11 rows 2 - 3, the fluorescence of rhodamine B became obvious at 9 min

when treated with RB/NLC. These demonstrated that RB/NLC can enter into cell's

cytoplasm quickly. In fact, it is realized that many therapeutics (e.g. anti-cancer drugs,

photosensitizers and anti-oxidants) and biotherapeutics (e.g. peptide and protein drugs,

DNA and siRNA) have to be delivered and released into the cellular compartments

such as the cytoplasm or cell nucleus, in order to exert therapeutic effects (Torchilin.,

2006; Nori et al., 2005).

Fig 11. R1(A): control, without RB-NLC treatment; R1(B): HeLa cells were treated

with RB-NLC for 2 h; R2, 3: Red fluorescence from Rhodamine B, where the Hela

cells incubated with RB/NLC at the time of 0, 3, 6, 9,12, 15 minutes, respectively.

All images were captured by Cell'R Live Cell Station (×60).

4. Conclusion

A system of the NLC, i.e. nanostructured lipid carrier, was successfully

developed in this study for controlled and sustainable delivery of anticancer drugs

with CMT-3 as a model drug. The ratios between lipids, drug and surfactants and lipid

types, were studied for their effect on long term stability and uniformity of

nanoparticles size distribution. The NLC particle size (diameter) was about 150 nm

during the 30 days observation period with about 90% encapsulation efficiencies.

SANS showed that CMT/NLC owns smoother surface than blank NLC. And the

shapes of CMT/NLC become elongated, which coincided to SEM result. The

3-dimensional structures of CMT/NLC and blank NLC were cubic according to the

results of SAXS, which was suspected to attribute the burst-sustained release model of

CMT/NLC. The in vitro cellular cytotoxicity assay (MTT) data suggested that NLC

was not cytotoxic to HeLa cells under test conditions, but that CMT/NLC was more

cytotoxic than CMT at the same drug concentration. The increased toxicity of

CMT/NLC was attributed to the increased solubility of CMT-3, a hydrophobic

anticancer drug, in the CMT/NLC formulation. More time exposures resulted in

higher cellular cytotoxicity was agreement with the sustained release properties of

CMT/NLC. Moreover, the possible location of NLC at cytoplasm should also be

favorable to the cytotoxicity improvement of CMT-3. Of course, the exploration of

nano-material carrier to fit CMTs still has a lot of work to do, which will be our next

further research plan.

We would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Leonard I Wiebe for thoughtful

discussions. A. Z. gratefully acknowledges the support of this work by the Alexander

von Humboldt Foundation. We gratefully acknowledge the support of this work by

Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (201003047) and Fundamental

Research Funds for the Central Universities (WK1014024). SANS measurements

have been performed under the support of the European Commission (Grant

agreement N 226507-NMI3). Laszlo Almasy is acknowledged for help during SANS

measurements. Daniel Laipple is acknowledged for help during SEM measurements.

References

Brandenburg, K., Richter, W., Koch, M.H.J., Meyer, H.W., Seydel, U., 1998.

Characterization of the nonlamellar cubic and HⅡ structures of lipid A from

Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota by X-ray diffraction and freeze-fracture

electron microscopy. Chem.Phys.Lipids. 91, 53-69.

Delmas, T., Couffin, A.C., Bayle, P.A., Crecy, F., Neumann, E., Vinet, F., Bardet, M.,

Bibette, J., Texier, I., 2011. Preparation and characterization of highly stable lipid

nanoparticles with amorphous core of tuneable viscosity. Colloid Interface Sci. 360,

Dreiss, C. A., 2007. Wormlike micelles: Where do we stand? Recent developments,

linear rheology and scattering to techniques. Soft Matter. 956-970.

Eliana, B.S., Rainer, M.H., 2010. Lipid Nanoparticles: Effect on Bioavailability and

Pharmacokinetic Changes. Drug delivery. 115-134.

Ezrahi, S., Tuval, E., Aserin, A., 2006. Properties, main applications and perspectives

of worm micelles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 77-102.

Geng. Y., Discher. D. E., 2005. Hydrolytic degradation of poly(rthylene

oxide)-block-poly(caprolactone) worm micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.12780-12781.

Geng. Y., Dalhaimer. P., Cai. S., Tsai. R., Tewari. M., Minko. T., Discher. D.E., 2007.

Shape effects of filaments versus spherical particles in flow and drug delivery. Nat,

Nanotechnol. 249-255.

Glatter. O., 1977. A new method for the evaluation of small-angle scattering data. J.

Appl. Cryst. 10, 415-421.

Golub, L.M., Ramamurthy, N.S., McNamara, T.F., Greenwald, R.A., Rifkin, B.R.,

1991. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown: new therapeutic

implications for an old family of drugs. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2, 297-321.

Gu, Y., Lee, H.M., Roemer, E.J., Musacchia, L., Golub, L.M., Simon, S.R., 2001.

Inhibition of tumor cell invasiveness by chemically modified tetracyclines. Curr

Med Chem. 8, 261–270.

Ji, J.G., Wu, D.J., Liu, L., Chen, J.D., Xu, Y., 2012. Preparation, characterization, and

in vitro release of folic acid-conjugated chitosan nanoparticles loaded with

methotrexate for targeted delivery. Polym. Bull. 68, 1707-1720.

Khalil, M., Ranjita, S., Sven, G., Cecilia, A., Rainer, M.H., 2011. Lipid nanocarrier for

dermal delivery of lutein: Prepartion, characterization, stability and performance.

Int J Pharm. 414, 267-275.

Patricia, S., Samantha, C.P., Eliana, B.S., Maria, H.A.S., 2011. Polymorphism,

crystallinity and hydrophilic-lipophilic balance of stearic acid and stearic

acid-capric/caprylic triglyceride matrices for production of stable nanoparticles.

Colloid and Surface B: Biointerfaces. 86, 125-130.

Lokeshwar, B.L., Selzer, M.G., Zhu, B.Q., Block, N.L., Golub, L.M., 2002. Inhibition

of cell proliferation, invasion, tumor growth and metastasis by an oral

non-antimicrobial tetracycline analog (COL-3) in a metastatic prostate cancer

model. Int J Cancer. 98, 297-309.

Lokeshwar, B.L., 1999. MMP inhibition in prostate cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 878,

Lokeshwar, B.L., Houston-Clark, H.L., Selzer, M.G., Block, N.L., Golub, L.M., 1998.

Potential application of a chemically modifiednon-antimicrobial tetracycline

(CMT-3) against metastatic prostate cancer. Adv Dent Res. 12, 97–102.

Lokeshwar, B.L., Escatel, E., Zhu, B., 2001. Cytotoxic activity and inhibition of

tumor cell invasion by derivatives of a chemically modified tetracycline CMT-3

(COL-3). Curr Med Chem. 8, 271–279.

Lokeshwar, B.L., Selzer, M.G., Zhu, B.Q., Block, N.L., Golub, L.M., 2002. Inhibition

of cell proliferation, invasion, tumor growth and metastasis by an oral

non-antimicrobial tetracycline analog (COL-3) in a metastatic prostate cancer

model. Int J Cancer.98, 297–309.

Lopes, R., Eleuterio, C.V., Goncalves, L.M.D., Cruz, M.E.M., Almeida, A.J., 2012.

Lipid nanoparticles containing oryzalin for the treatment of leishmaniasis. Eur J

Pharm Sci. 45, 442-450.

Liu, Y., Wang, P.F., Sun, C., Feng, N.P., Zhou, W.X., Yang, Y., Tan, R., Chen, Z.Q.,

Wu, S., Zhao, J.H., 2010. Wheat grem agglutinin-grafted lipid nanoparticles:

Preparation and in vitro evaluation of the association with Caco-2 monolayers. Int J

Pharm. 397, 155-163.

Mariani, P., Luzzati, V., Delacroix, H., 1993. Cubic phases of lipid-containing

systems. Structure analysis and biological implications. J. Mol. Biol. 204, 165-189.

Medha, D.J., Rainer, M.H., 2009. Lipid nanoparticles for parenteral delivery of

actives. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 71, 161-172.

Meng, Q., Xu, J., Goldberg, I.D., Rosen, E.M., Greenwald, R.A., Fan, S., 2000.

Influence of chemically modified tetracyclines on proliferation, invasion and

migration properties of MDA-MB-468 human breast cancer cells. Clin Exp

Metastasis.18, 139-46.

Nori, A., Kopecek, J., 2005. Intracellular targeting of polymer-bound drugs for cancer

chemotherapy. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 57, 609-636.

Nukolova, N.V., Oberoi, H.S., Cohen, S.M., Kabanov, A.V., Bronich, T.K., 2011.

Folate-decorated nanogels for targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Biomaterials. 32,

Radheshyam, T., Kamla, P., 2011. Nanostructured lipid carrier versus solid lipid

nanoparticles of simvastain: Comparative analysis of characteristics,

pharmacokinetics and tissues uptake. Int J Pharm. 415, 232-243.

Rainer, M.H., 2007. Lipid nanoparticles: recent advances. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 59,

Rainer, M.H., Cornelia, M.K., 2004. Challenges and solutions for the delivery of

biotech drugs-a review of drug nanocrystal technology and lipid nanoparticles. J of

Biotechnology. 113, 151-170.

Rosta L., 2002. Cold neutron research facility at the Budapest Neutron Centre. Appl

Phys. A. 74, S292-S294.

Schmidt, P. W., 1995. Some Fundamental Concepts and Techniques Useful in

Small-Angle Scattering Studies of Disordered Solids. In Modern Aspects of

Small-Angle Scattering; Brumberger, H., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: The

Netherlands, pp 1-56.

Seftor, R.E., Seftor, E.A. De, Larco, J.E., Kleiner, D.E., Leferson, J.,

Stetler-Stevenson, W.G., McNamara, T.F., Golub, L.M., Hendrix, M.J., 1998.

Chemically modified tetracyclines inhibit human melanoma cell invasion and

metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 16, 217-25.

Selzer, M.G., Zhu, B., Block, N.L., Lokeshwar, B.L., 1999. CMT-3, a chemically

modified tetracycline, inhibits bony metastases and delays the development of

paraplegia in a rat model of prostate cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 878, 678–682.

Soheila, K., Ebrahim, V.F., Mohsen, N., Fatemeh, A., 2010. Preparation and

characterization of ketoprofen-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles made from beeswax

and carnauba wax. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 6,

Seydel, U., Brandenburg, K., Koch, M.H.J., Rietschel, E.T., 1989. Supramolecular

structure of lipopolysaccgaride and free lipid Aunder physiological conditions as

determined by synchrotron small-angle X-ray diffraction. Eur. J. Biochem. 186,

Syed S, Takimoto C, Hidalgo M, Rizzo J, Kuhn JG, Hammond LA, Schwartz G,

Tolcher A, Patnaik A, Eckhardt SG, Rowinsky EK. A phase I and pharmacokinetic

study of Col-3 (Metastat), an oral tetracycline derivative with potentmatrix

metalloproteinase and antitumor properties. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;

Sylvia, A.W., Rainer, M.H., 2004. Solid lipid mamoparticles for parenteral drug

delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 56, 1257-1272.

Torchilin, V.P., 2006. Recent approaches to intracellular delivery of drugs and DNA

and organelle targeting. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 8, 343-375.

Veerawat, T., Prapaporn, B., Eliana, B.S., Rainer, M.H., Varaporn, B.J., 2008.

Influence of oil content on physicochemical properties and skin distribution of Nile

red-loaded NLC. J Control Release. 128, 134-141.

Venkateraman, S., Hedrick, J.L., Ong, Z.Y., Yang, C., Ee, P.L.R., Hammond, P.T.,

Yang, Y.Y., 2011. The effects of polymeric nanostructure shape on drug delivery.

Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 63, 1228-1246.

Wang, J.J., Liu, K.S., Sung, K.C., Tsai, C.Y., Fang, J.Y., 2009. Lipid nanoparticles

with different oil/fatty eater ratios as carrier of buprenorphine and its prodrugs for

injection. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 38, 138-146.

Xu, Z.H., Chen, L.L., Gu, W.W., Gao,Y., Lin, L.P., Zhang, Z.W., Xi, Y., Li, Y.P., 2009.

The performance of docrtaxel-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles targeted to

hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomaterial. 30, 226-232.

Yoo, J.W., Doshi, N., Mitragotri, S., 2011. Adaptive micro and nanoparticles:

Temporal control over carrier properties to facilitate drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv

Rev. 63, 1247-1256.

Zhigaltsev, I.V., Winters, G., Srinivasulu, M., Crawford, J., Wong, W., Amankwa, L.,

2010. Development of a weak-base docetaxel derivative that can be loaded into

lipid nanoparticles. J Control Release. 144, 332-340.

Figure Legends

Figure 1. The structures of doxycycline (upper) and CMT-3 (lower).

Fig 2. The effects of lipids and CMT-3 concentration on entrapment efficiency and

drug loading. *The labels of samples are the same as in Table. 3. Values are mean ±

Fig 3. AFM images of blank-NLC (A), and CMT/NLC (B).

Fig 4. The SEM photographs of blank-NLC (A) and CMT loaded NLC (B).

Fig 5. SANS spectra of NLC before and after loaded with CMT-3 in PBS (A); P(r)

function obtained from the corresponding scattering curves in A.

Fig 6. SAXS curve for film freeze-dried blank-NLC and CMT/NLC at 25 °C.

Fig 7. X-ray diffraction analysis of CMT-3 formulations: X-ray powder

diffractograms of CMT-3 (A), freeze-dried unloaded blank-NLC (B) and freeze-dried

Fig 8. The in-vitro release study. Cumulative release of CMT-3 from CMT/NLC in

different release mediums (A, Values are mean ± SD (n=3)), and average release rate

of CMT-3 from CMT/NLC in pH release medium (B).

Fig 9. In vitro cytotoxicity of CMT-3 and CMT/NLC against HeLa cells for 24 h (A)

or 48 h (B). Cell viability is expressed as the percentage of untreated controls. Data

are given as mean±SD (n=6). *p < 0.05 compared with CMT-3.

Fig 10. HeLa cells were treated with different medium for 6 h: A. control, without any

treatment; B. 20 μM CMT-3; C. blank-NLC (same volume with CMT/NLC); D.

CMT/NLC (CMT concentration is 20 μM). Cells were captured by digital camera

Fig 11. R1(A): control, without RB-NLC treatment; R1(B): HeLa cells were treated

with RB-NLC for 2 h; R2, 3: Red fluorescence from Rhodamine B, where the Hela

cells incubated with RB/NLC at the time of 0, 3, 6, 9,12, 15 minutes, respectively.

All images were captured by Cell'R Live Cell Station (×60).

Table legends

Table 1. Effects of lipid ingredients on mean particle size of blank-NLC.

Table 2. Effects of the concentration of surfactants on mean particle size and stability.

Table 3. The effects of lipids and CMT-3 content on mean particle size. Values are

mean ± SD (n=3)

Source: http://www.coastdat.eu/imperia/md/content/hzg/zentrale_einrichtungen/bibliothek/journals/2013/yang_30730.pdf

Control of Medical Journal Content: Suppressing the MBT Contamination Warning (Chapter 8, The Nurses are Innocent – The Digoxin Poisoning Fallacy, Dundurn Press, 2011) Key words: adverse reactions, Apotex, Avandia, benoxaprofen, deferiprone, drug companies, editorial interference, injection contamination, medical ethics, medical journals, MBT (mercapto-benzothiazole), Olivieri

Evaluations that make a Evaluations that make a difference-EN-20Sep15.indd 1 21/09/2015 13:14:17 Evaluations that make a difference-EN-20Sep15.indd 2 21/09/2015 13:14:18 extent possible, from the perspective The story of this project of the users and beneficiaries who have The issue of evaluation use is gaining been involved in the profiled evaluations