Nickelridge.ca

Multiple daily administrations of low-dose

sublingual immunotherapy in allergic

rhinoconjunctivitis

Vasco Bordignon, MD,* and Samuele E. Burastero, MD†

Background: Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) is an efficacious treatment for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.

Objective: To investigate whether the number of daily administrations of SLIT can affect its efficacy.

Methods: In an open study, 64 patients with allergic seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis to grass or birch pollens were assigned to

the following 2-year daily treatment schedules: "3–3" group, 1 drop 3 times daily for 2 years; "2–3" group, 1 drop twice dailyin year 1 and 1 drop 3 times daily in year 2; "1–3" group, 1 drop once daily in year 1 and 1 drop 3 times daily in year 2; andcontrol group, no treatment. One fifth of the allergen concentration recommended by the manufacturer as maintenance treatmentwas used throughout the study. Patients were monitored for skin reactivity to the allergen used for SLIT using an end pointdilution technique and for drug use.

Results: No treatment-related adverse effects were observed. Skin reactivity to allergen decreased compared with controls in

the first treatment year only in the "3–3" group and in all treated patients in year 2. Drug use decreased in the first treatment yearin the "3–3" and "2–3" groups vs controls. This outcome extended to "1–3" patients in treatment year 2. Antihistamine usedecreased significantly compared with baseline in year 1 in "3–3" and "2–3" patients and in all treated patients in year 2. Nochanges were observed in controls.

Conclusion: The number of daily administrations seems to correlate with the efficacy of SLIT.

Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:158–163.

that caution should be maintained in attributing a critical role

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) is a safe and efficacious

to SLIT doses to achieve clinical efficacy and that dedicated

treatment for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.1,2 The efficacy of

studies should instead be focused on the effect of the fre-

SLIT has been reported with a wide range of treatment doses,

quency of immunotherapy administration.

5 to 375 times those used for subcutaneous immunotherapy(SCIT).3,4 It is unclear whether a dose-response relationship

MATERIALS AND METHODS

exists with efficacy, although at least 1 study5 directly sug-gests that this is indeed the case. Furthermore, different

Study Design

weekly schedules are still used (3 times a week, every other

We conducted a 3-year open study of 64 patients (age range,

day, and so on).6 It was previously observed that patients

4 –50 years) with allergic seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis to

treated according to a daily allergen administration schedule,

grass or birch pollens. Patients underwent an accurate anam-

despite a lower cumulative dose, showed a higher reduction

nesis and clinical examination, including rhinologic exami-

in drug intake than patients treated with 3 weekly allergen

nation with the evaluation of anatomical problems (such as

administrations.7 These data suggest that the frequency of

nasal septum deviation), the nature of symptoms (rhinorrhea,

SLIT administration could be crucial to its efficacy and

nasal obstruction, associated ocular problems, cough, or

possibly more so than the absolute amount of the adminis-

asthma), and the seasonality, if any, of each symptom. A

tered dose. To evaluate the relevance of this assumption, we

daily immunotherapy schedule was given, which was started

used markedly low-dose SLIT to evaluate whether this treat-

before the pollen season in the first treatment year (in De-

ment is still efficacious when administered in protocols im-

cember 2000 and February 2001 for patients allergic to birch

plying different numbers of daily dosages. We found a strik-

and grass, respectively) without a build-up phase. Immuno-

ing correlation between the number of daily dosages and both

therapeutic treatment lasted 2 years.

the clinical efficacy and the reduction in skin reactivity to

allergen after only 1 year of SLIT. These results were con-

Patients were enrolled as volunteers after having been in-

solidated in the second treatment year. These data suggest

formed in full detail about the methods and aims of the trial.

Patients or their parents signed an informed consent form.

The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical

* Bassano del Grappa (VI), Italy.

standards of the responsible institutional committee on hu-

† Department of Biotechnology, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

man experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of

Received for publication December 21, 2005.

Accepted for publication in revised form February 27, 2006.

1975, as revised in 1983.

ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA & IMMUNOLOGY

The study inclusion criteria were as follows: allergic sea-

the diagnostic extract prepared in sterile solution immediately

sonal rhinoconjunctivitis (without asthma) for at least 2 years;

before the assay. Saline solutions and histamine hydrochlo-

sensitization limited to either grass or birch pollens, as eval-

ride (ALK-Abello ) were used as negative and positive con-

uated by means of skin prick testing and serum specific IgE

trols, respectively. All the skin tests were performed by the

measurement; living in northern Italy; and only partial control

same individual (V.B.).

of allergic symptoms, never complete and satisfactory to the

To avoid any interference due to exposure to the relevant

patient, with the use of antihistamines (either cetirizine or

environmental allergen, the skin end point test was performed

loratadine). The study exclusion criteria were as follows:

outside the pollination period of the sensitizing species (ie, in

asthma or nasal polyps or obstructive nasal septum deviation;

February and December for patients allergic to grass and

a clinical history of significant symptomatic perennial aller-

trees, respectively). The test was performed at the beginning

gic rhinitis or asthma caused by an allergen to which the

of the first (observational) year to evaluate baseline reactivity

patient was regularly exposed; a clinical history of significant

and was repeated in the same months after the symptomatic

recurrent acute sinusitis (defined as 2 episodes per year for

seasons of each treatment year. Positivity was expressed as

the past 2 years, all of which required antibiotic drug treat-

the highest dilution yielding a wheal diameter greater than 3

ment) or chronic sinusitis or chronic obstructive lung disease;

mm. Using this end point dilution skin test, all patients

and, at randomization, current symptoms of, or treatment for,

included in the study scored positive at the 1:64 dilution (or

upper respiratory tract infection, acute sinusitis, acute otitis

above) at baseline.

media, or other relevant infectious processes.

Patients who met the study criteria and who were willing to

participate in the study were consecutively assigned to 1 of 3

In each treatment group, mixed birch or grass allergen ex-

treatment schedules: "3–3" group (n ⫽ 18), 1 drop 3 times

tracts (ALK Abello ) were used at one fifth of the concentra-

daily for 2 years; "2–3" group (n ⫽ 18), 1 drop twice daily in

tion recommended by the manufacturer as maintenance ther-

year 1 and 1 drop 3 times daily in year 2; and "1–3" group

apy (ie, 200 standard treatment units/mL). For each

(n ⫽ 18), 1 drop once daily in year 1 and 1 drop 3 times daily

administration, a single drop of the extract at this concentra-

in year 2. Patients who met the inclusion criteria but who did

tion was used 1, 2, or 3 times a day, according to the

not want to perform immunotherapy served as untreated

experimental group. In the conventional immunotherapy pro-

controls (n ⫽ 10). Patients were not informed that different

tocol, this dose would have to be scaled up to 5 drops and

numbers of drops were prescribed to different patients to

followed by a further step to a dosage 5 times higher to reach

prevent the possibility that "the more the better" hypothesis

maintenance. The timing of immunotherapy administration

could affect the individual perception of the need for antihis-

was as follows: (1) 8 AM for the once daily schedule (the first

tamines. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

year of treatment in the "1–3" group), (2) 8 AM and 8 PM forthe twice-daily schedule (the first year of treatment in the

Skin Testing and Allergen Extracts Used for Diagnosis

"2–3" group), and (3) 8 AM, 2 PM, and 10 PM for the 3 times

The skin response to the sensitizing allergen was quantified

daily schedule (the first year of treatment in the "3–3" group

using skin prick tests with mixed grasses (

Poa pratensis,

and the second year treatment in all the treated groups).

Phleum pratense, Dactylis glomerata, Festuca pratensis, and

Lolium perenne) and mixed Betulaceae (

Betula alba, Alnus

Drug Use Score

glutinosa, and

Corylus avellana) commercial extracts (ALK

As stated, at enrollment, all patients had a history of at least

Abello , Milan, Italy) by means of an end point dilution

2 years of allergic symptoms, which required exclusively the

technique. Each allergen extract was prepared in a saline

administration of oral antihistamines. Drug use was quanti-

solution containing glycerol, 50% vol/vol, and phenol, 0.4%

fied as the number of days during which the antihistamine

wt/vol, and was preliminarily used undiluted to evaluate the

(cetirizine or loratadine) was taken in each symptomatic

monosensitization of the patient. Then, the previously de-

season. In the geographic area where patients were living, the

scribed end point technique was used.7 Briefly, this method

average duration of the allergic season is approximately 90

implied 12 consecutive half dilutions in a saline solution of

days for birch and grass pollens.

Table 1. Characteristics of 64 Patients With Allergic Seasonal Rhinoconjunctivitis to Grass or Birch Pollens*

Allergic patients, No.

Sex, M/F, No.

Age, mean (range), y

* See the "Patient Enrollment" subsection for definitions of the treatment groups.

VOLUME 97, AUGUST, 2006

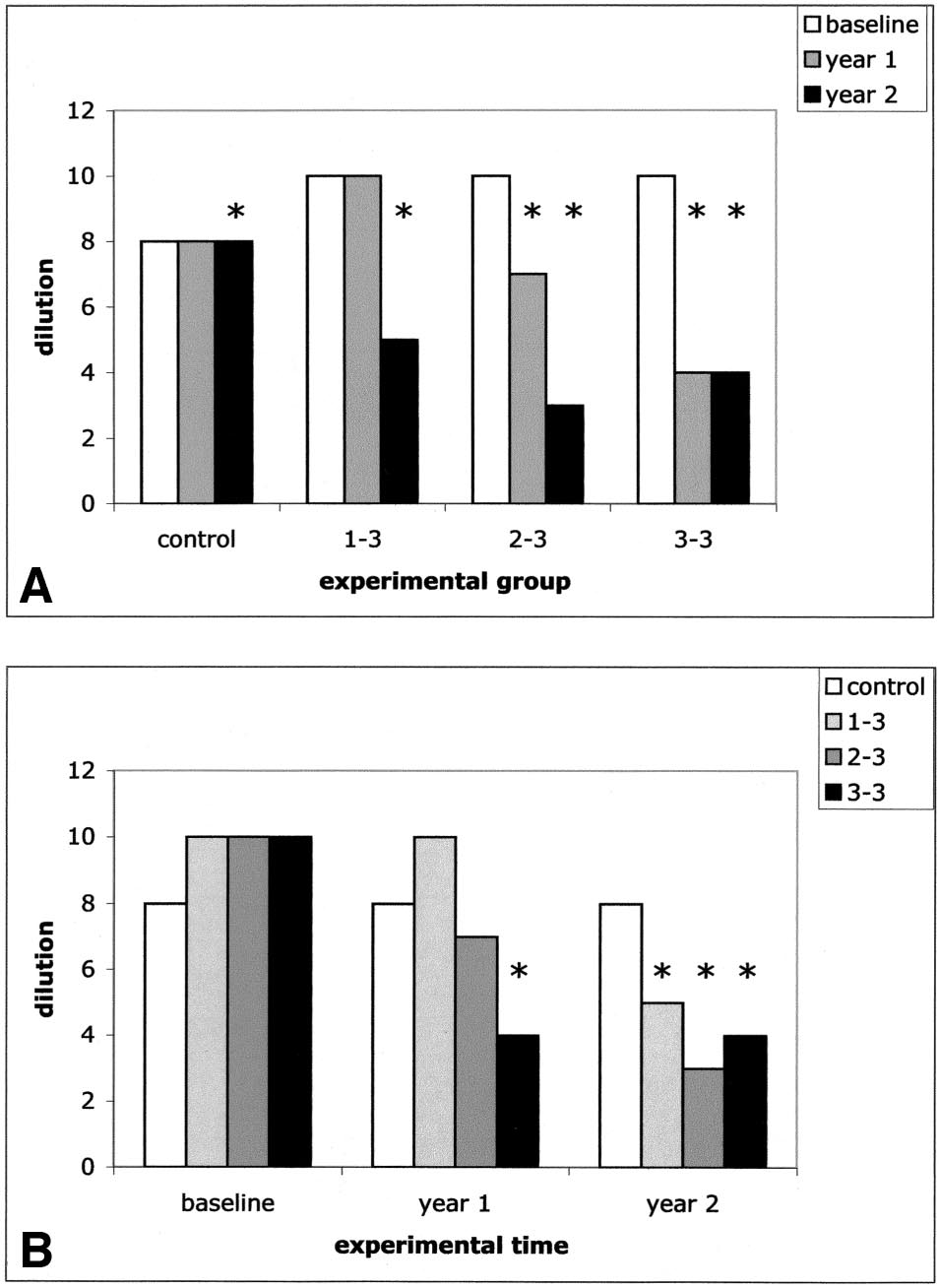

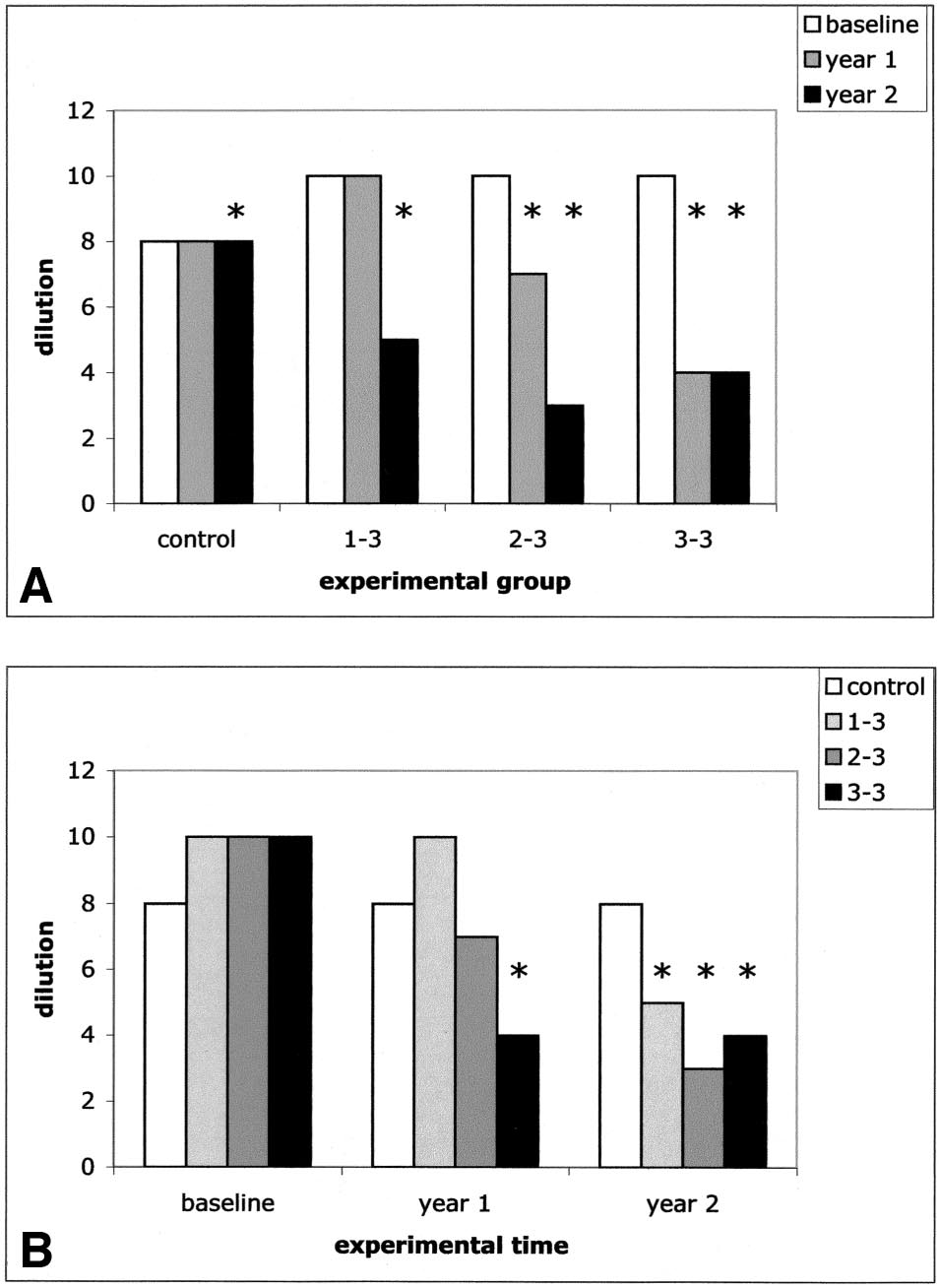

Skin Test Reactivity

Statistical analysis was performed by means of nonparametric

In the intragroup analysis, skin reactivity significantly de-

tests (the Wilcoxon test for intragroup comparison and the

creased compared with baseline in only "3–3" and "2–3"

Mann-Whitney test for intergroup comparison) because none

patients after the first treatment year (P ⬍ .001 and P ⫽ .002,

of the examined data could be considered for normal distri-

respectively) and in all treated patients after the second treat-

bution either directly or following common mathematical

ment year (P ⬍ .001) (Fig 1A and Table 2). In contrast, in the

transformations. The statistical analysis was performed using

control group, skin reactivity did not change in the first year

a software program (GraphPad; GraphPad Software, San

and increased compared with baseline in the second year of

Diego, CA). P ⱕ .05 was considered statistically significant.

follow-up (P ⫽ .03). In the intergroup analysis, values of skinreactivity to each sensitizing allergen were homogeneous in

the 4 experimental groups at baseline (Fig 1B). After 1 year

Adverse Effects

of treatment, skin reactivity decreased compared with con-

No SLIT-related adverse effects were observed in any of the

trols in the "3–3" group (P ⬍ .001) but not in the "2–3" and

treated groups. Although no build-up phase was performed at

"1–3" groups. After 2 years of treatment, skin reactivity

the beginning of the study, neither local (oral) adverse effects

decreased compared with controls in all the treated groups

nor systemic symptoms (rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, urti-

(P ⬍ .001) (Fig 1B and Table 2).

caria, or pruritus) were observed. No dropouts were observed.

Comparing skin reactivity in the "1–3" group vs the "2–3"

group, the "1–3" group vs the "3–3" group, and the "2–3"group vs the "3–3" group at baseline, no differences wereobtained, indicating a homogeneous level of allergen-specificsensitization at the recruitment of patients. At year 1, "2–3"and "3–3" patients reached a lower level of sensitizationcompared with "1–3" patients (P ⬍ .001). Furthermore, atyear 1, "3–3" patients lowered their sensitization comparedwith "2–3" patients (P ⬍ .001). At year 2, "2–3" and "3–3"patients reached a lower level of sensitization compared with"1–3" patients (P ⬍ .001), whereas no difference occurredbetween "2–3" and "3–3" patients.

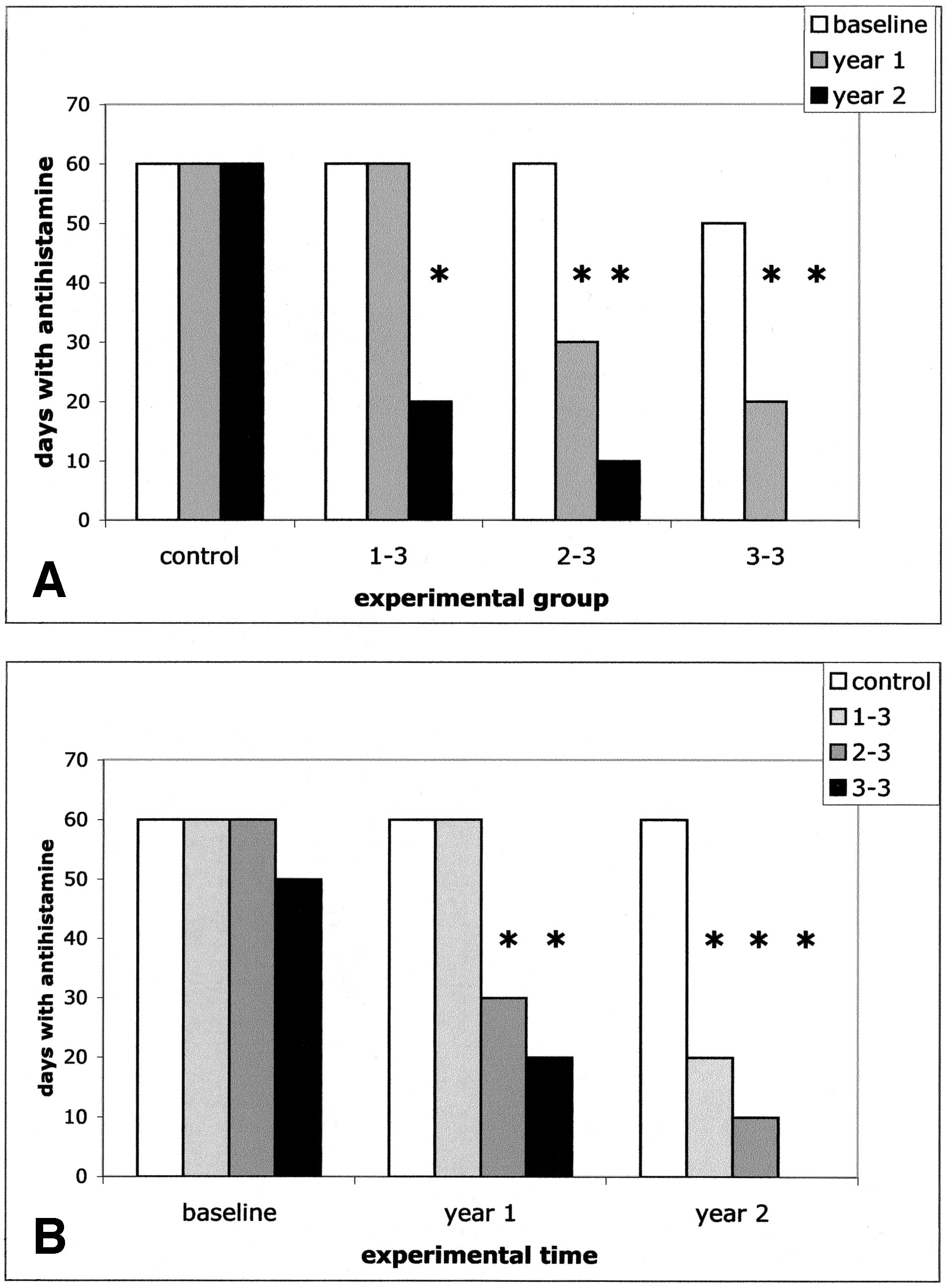

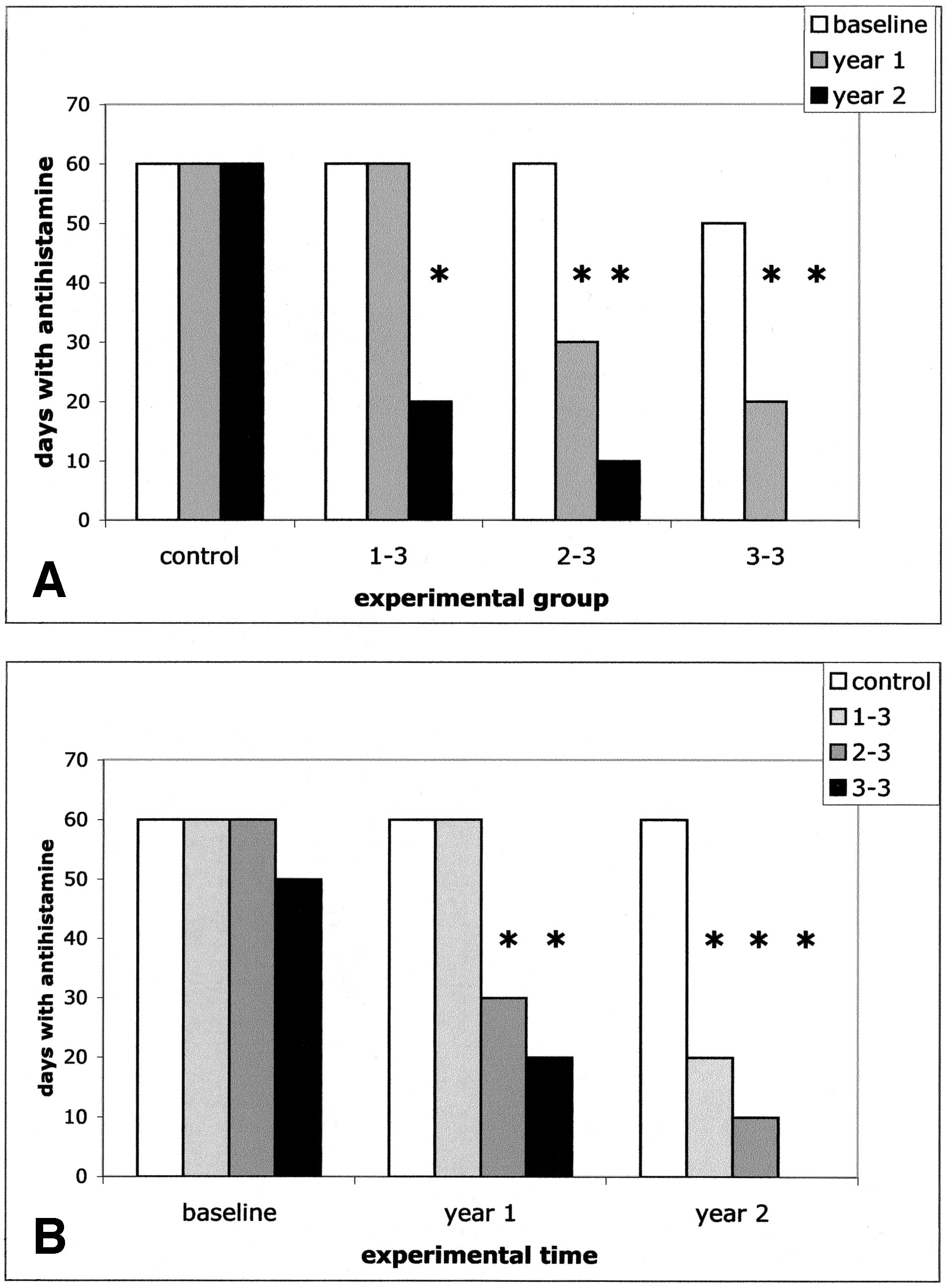

Drug UseIn the intragroup analysis, antihistamine use decreased sig-nificantly compared with baseline in the first treatment yearonly in the "3–3" and "2–3" groups but not in "1–3" patients(P ⬍ .001) and in all treated patients in the second treatmentyear (P ⬍ .001). No changes were observed in controls (Fig2A and Table 2). In the intergroup analysis, at baseline,treated patients were similar to controls regarding antihista-mine use (Fig 2B and Table 2). In contrast, in the first

Table 2. Skin Reactivity and Drug Use in the Experimental Groups*

Value, median (IQR)

Skin reactivity (reverse of dilution)

Figure 1. Median values of skin reactivity at the 3 considered experimen-

Drug use (days with antihistamine therapy)

tal times. The median values of the reverse of dilution yielding wheals with

a diameter greater than 3 mm are indicated for representative purposes. A,

The intragroup analysis shows the modification across time of skin reactivity

in each experimental group. B, The intergroup analysis shows the compar-

ison at each experimental time of skin reactivity in the 3 experimentalgroups. Asterisks indicate the significant differences of the considered values

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

compared with baseline values of the same experimental group (A) or

* See the "Patient Enrollment" subsection for definitions of the treat-

compared with time-matched values of controls (B).

ment groups.

ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA & IMMUNOLOGY

DISCUSSION

Sublingual immunotherapy is a safe and effective alternative

to injection immunotherapy for respiratory allergic diseas-

es.8–16 A rigorous meta-analysis1 of evidence-based studies

has recently established this conclusion. Herein, we confirm

the efficacy of SLIT, which induced the reduction of 2 end

points (skin reactivity to allergen and antihistamine use) in

monosensitized patients with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunc-

tivitis.

We found a direct correlation between the improvement of

end points and the number of daily administrations. To makeit unlikely that the slightly different allergen doses related tothe different number of daily dispensations could explain theresults, we administered an amount of allergen approximatelyone fiftieth of that recommended by the manufacturer(namely, 2%, 4%, and 6% of the daily recommended dose inthe first treatment year of "1–3," "2–3," and "3–3" patients,respectively). As a whole, the administered dose corre-sponded to 0.56, 0.37, and 0.18 times the cumulative monthlySCIT dose in the "3–3," "2–3," and "1–3" groups, respec-tively. The SLIT/SCIT ratio of dosages is an imperfect way toexpress the allergen dose, which should be accepted withsome caution until the content in recombinant allergen isprovided for all available extracts. However, these figures arefar below the lower value of the wide dose range (5–375times), which seemed efficacious in a meta-analysis3 of evi-denced-based SLIT studies with schedules implying singledaily administrations. Indeed, in a consensus document from

Figure 2. Median values of antihistamine use at the 3 considered exper-

the Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma group, effi-

imental times. The number of days with antihistamine use is indicated. A,

cacy was attributed to even higher SLIT doses, in the 50 to

The intragroup analysis shows the modification across time of drug use in

100 SLIT/SCIT ratio, or above.17 In contrast to these argu-

each experimental group. B, The intergroup analysis shows the comparisonat each experimental time of drug use in the 3 experimental groups. Asterisks

ments, with the extremely low doses we used, the impact of

indicate the significant differences of the considered values compared with

SLIT on skin reactivity to the relevant allergen and on the

baseline values of the same experimental group (A) or compared with

drug use scores was critically dependent on the number of

time-matched values of controls (B).

daily assumptions. Indeed, despite these remarkably lowdoses, a formally more appropriated experimental designwould have been to compare the usual once-daily dose with

treatment year, "3–3" and "2–3" patients reached lower drug

the same amount divided into 2 or 3 doses rather than simul-

use compared with controls (P ⬍ .001 and P ⬍ .02, respec-

taneously changing frequency and dose. However, the results

tively). The reduction in drug use compared with controls

suggest that in determining SLIT efficacy, allergen persis-

extended to "1–3" patients in the second treatment year (P ⬍

tence represents a far more relevant factor than its concen-

.001) (Fig 2B and Table 2).

Comparing the use of drugs in the "1–3" group vs the

Although this is an open study, the fact that such an

"2–3" group, the "1–3" group vs the "3–3" group, and the

objective end point as skin reactivity was modulated in par-

"2–3" group vs the "3–3" group at baseline, no differences

allel to drug use suggests that indeed the immune response

were observed, indicating a homogeneous level of clinical

mutated in response to the number of daily drops taken by

severity at the recruitment of patients. At year 1, "2–3" and

patients, bringing about the observed clinical consequences.

"3–3" patients decreased drug use compared with "1–3"

Furthermore, although symptom scores were not collected

patients (P ⬍ .001). Furthermore, at year 1, "3–3" patients

with daily diaries, a clear-cut improvement in "3–3" patients

had lower drug use compared with "2–3" patients (P ⬍ .002).

was observed after a single year of treatment compared with

At year 2, "2–3" and "3–3" patients had lower drug use

the previous season in terms of overall self-evaluation of

compared with "1–3" patients (P ⬍ .003 and P ⬍ .001,

symptoms and with respect to answers to questions about

respectively). Furthermore, at year 2, "3–3" patients used

quality of life. Furthermore, this improvement extended to the

fewer drugs than "3–3" patients (P ⬍ .04).

other groups when the "3–3" dosage was applied to them.

VOLUME 97, AUGUST, 2006

Recently, the dose-response dependence of the efficacy

would also lower the cost of treatment and avoid the induc-

and severity of adverse effects has been considered in 2

tion phase. This issue deserves to be investigated more ex-

dedicated studies,5,18 although within a narrow dose range,

tensively in double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of ho-

and in 1 meta-analysis.19 Furthermore, the possibility that

mogenous cohorts (ie, either adults or children with

precoseasonal treatment may be as efficacious as a perennial

sensitization to a single allergen). This approach should par-

treatment has been reported.6,20 However, the relevance of the

allel current efforts with high-dose regimens.5,18

number of daily administrations in obtaining efficacious clin-ical results has never been addressed directly. It was previ-

ously observed that patients treated according to a daily

1. Wilson DR, Lima MT, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy

allergen administration schedule, despite a lower cumulative

for allergic rhinitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Al-lergy. 2005;60:4 –12.

dose, showed a significantly greater decrease in skin reactiv-

2. Novembre E, Galli E, Landi F, et al. Coseasonal sublingual

ity, a higher rate of no use of any drug, and a more than 50%

immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children

reduction in yearly drug intake compared with patients

with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;

treated with 3 weekly allergen administrations.7 These data

114:851– 857.

were obtained as side results in a study focused on the

3. Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. Noninjection routes for immu-

modulation of skin reactivity to the allergen. Nevertheless, it

notherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:437– 449.

was indicating that the number of daily administrations of a

4. Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Allergic rhinitis

sublingual vaccine could be more critical in obtaining a

and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:

favorable modulation of immunity to allergens than the

amount of the administered allergen itself. The biological

5. Marcucci F, Sensi L, Di Cara G, et al. Dose dependence of

immunological response to sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy.

mechanisms that underlie SLIT efficacy are still largely un-

known and remain a matter of speculation.21 Thus, it should

6. Di Rienzo V, Puccinelli P, Frati F, et al. Grass pollen specific

not be surprising that dose-response rules cannot be applied

sublingual/swallow immunotherapy in children: open-

tout-court to the allergic response involving such an immune-

controlled comparison among different treatment protocols. Al-

privileged site as the oral mucosa. Indeed, our results can

lergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1999;27:145–151.

easily be integrated with the established knowledge on oral

7. Bordignon V, Parmiani S. Variation of the skin end-point in

allergen absorption in SLIT. In fact, a study from Bagnasco

patients treated with sublingual specific immunotherapy. J In-

et al22 demonstrated that when performing SLIT, only a

vestig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2003;13:170 –176.

minimal amount of allergen is absorbed orally, but this has to

8. Tari MG, Mancino M, Monti G. Efficacy of sublingual immu-

be considered critical to the efficacy of SLIT. In contrast, the

notherapy in patients with rhinitis and asthma due to house dustmite: a double-blind study. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr).

gastrointestinal absorption, which is prevalent in SLIT itself

and represents the exclusive modality of absorption in oral

9. Troise C, Voltolini S, Canessa A, et al. Sublingual immuno-

immunotherapy, is not associated with any clinical improve-

therapy in Parietaria pollen-induced rhinitis: a double-blind

ment.23–28 Along this line, the allergen persistence in the oral

study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1995;5:25–30.

mucosa may be a far more relevant factor for gaining efficacy

10. Sabbah A, Hassoun S, Le Sellin J, et al. A double-blind,

than allergen concentration. It would be interesting to exper-

placebo-controlled trial by the sublingual route of immunother-

imentally compare with radiolabeled allergens the amount

apy with a standardized grass pollen extract. Allergy. 1994;49:

that is actually absorbed through the oral mucosa when using

a dose as low as one fiftieth of the recommended one.

11. Clavel R, Bousquet J, Andre C. Clinical efficacy of sublingual-

We suggest that multiple daily doses may provide a much

swallow immunotherapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlledtrial of a standardized five-grass-pollen extract in rhinitis. Al-

greater impact on the overall allergen absorption through the

lergy. 1998;53:493– 498.

oral mucosa than the concentration of the allergen or its

12. Feliziani V, Lattuada G, Parmiani S, et al. Safety and efficacy

cumulative amount. In principle, it cannot be excluded that

of sublingual rush immunotherapy with grass allergen extracts:

extremely high concentrations of allergen used in some SLIT

a double blind study. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1995;23:

trials may also imply longer persistence of the extract in the

mouth. This increased persistence could be responsible for

13. Quirino T, Iemoli E, Siciliani E, et al. Sublingual versus injec-

relatively greater efficacy5 rather than the dose itself, but at a

tive immunotherapy in grass pollen allergic patients: a double

given point this would be achieved at the cost of many and

blind (double dummy) study. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996;26:

annoying oral and gastrointestinal adverse effects.3,29

In conclusion, these data indicate that SLIT is safe and

14. Passalacqua G, Albano M, Fregonese L, et al. Randomised

controlled trial of local allergoid immunotherapy on allergic

efficacious in patients with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis also at

inflammation in mite-induced rhinoconjunctivitis. Lancet.

a low-dose regimen. The number of doses seems to be far

1998;351:629 – 632.

more crucial for SLIT efficacy than the absolute amount of

15. Vourdas D, Syrigou E, Potamianou P, et al. Double-blind,

administered allergen. Two daily doses are necessary to

placebo-controlled evaluation of sublingual immunotherapy

achieve clinical improvement, which is more consistent with

with standardized olive pollen extract in pediatric patients with

3 doses. Adoption of the concentration used in this study

allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and mild asthma due to olive pollen

ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA & IMMUNOLOGY

sensitization. Allergy. 1998;53:662– 672.

grass pollen to hay fever patients: an efficacy study in oral

16. Bousquet J, Scheinmann P, Guinnepain MT, et al. Sublingual-

swallow immunotherapy (SLIT) in patients with asthma due to

25. Taudorf E, Laursen LC, Lanner A, et al. Oral immunotherapy in

house-dust mites: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Al-

birch pollen hay fever. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;80:

lergy. 1999;54:249 –260.

17. Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P. Allergic rhinitis and its impact

26. Oppenheimer J, Areson JG, Nelson HS. Safety and efficacy of

on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S1–S315.

oral immunotherapy with standardized cat extract. J Allergy

18. Andre C, Perrin-Fayolle M, Grosclaude M, et al. A double-blind

Clin Immunol. 1994;93:61– 67.

placebo-controlled evaluation of sublingual immunotherapy

27. Van Deusen MA, Angelini BL, Cordoro KM, et al. Efficacy and

with a standardized ragweed extract in patients with seasonal

safety of oral immunotherapy with short ragweed extract. Ann

rhinitis: evidence for a dose-response relationship. Int Arch

Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1997;78:573–580.

Allergy Immunol. 2003;131:111–118.

28. Litwin A, Flanagan M, Entis G, et al. Oral immunotherapy with

19. Gidaro GB, Marcucci F, Sensi L, et al. The safety of sublingual-

short ragweed extract in a novel encapsulated preparation: a

swallow immunotherapy: an analysis of published studies. Clin

double-blind study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:30 –38.

Exp Allergy. 2005;35:565–571.

29. Burastero S. Regarding Gidaro GB, Marcucci F, Sensi L, In-

20. Gozalo F, Martin S, Rico P, et al. Clinical efficacy and tolerance

corvaia C, Frati F, Ciprandi G. The safety of sublingual-

of two year Lolium perenne sublingual immunotherapy. Aller-

swallow immunotherapy: an analysis of published studies. Clin

gol Immunopathol (Madr). 1997;25:219 –227.

Exp Allergy 2005;35:565–571. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:

21. Akdis CA, Blaser K. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immu-

1407–1408; author reply 1409.

22. Bagnasco M, Mariani G, Passalacqua G, et al. Absorption and

distribution kinetics of the major Parietaria judaica allergen(Par j 1) administered by noninjectable routes in healthy human

Requests for reprints should be addressed to:

beings. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:122–129.

Samuele E. Burastero, MD

23. Cooper PJ, Darbyshire J, Nunn AJ, et al. A controlled trial of

San Raffaele Scientific Institute

oral hyposensitization in pollen asthma and rhinitis in children.

via Olgettina 58

Clin Allergy. 1984;14:541–550.

20132 Milano, Italy

24. Taudorf E, Laursen LC, Djurup R, et al. Oral administration of

VOLUME 97, AUGUST, 2006

Source: http://nickelridge.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Bordignon-study.pdf

Design of the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) Protocol 054: A cluster randomized crossover trial to evaluate combined access to Nevirapine in developing countriesJim HughesUniversity of Washington, [email protected] Robert L. GoldenbergUniversity of Alabama, [email protected] Catherine M. WilfertElizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation/Duke University, [email protected]

STRUCTURE SEARCHING DERWENT WORLD PATENTS INDEX® (DWPISM) USING STN EXPRESS®: Part I INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SOLUTIONS BRIAN LARNER JANUARY 2013 – THE PROBLEM; WHY IS IT DIFFICULT TO SEARCH CHEMICAL STRUCTURES IN PATENTS? – SOLUTION; DWPI STRUCTURAL INDEXING – DWPI PATENT COVERAGE – COMPOUND COVERAGE – WHICH COMPOUNDS ARE – DETAILED LOOK AT BCE FRAGMENTATION CODING – DETAILED LOOK AT DCR – STRUCTURAL MANUAL CODES