Pri.rn.dk

Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure

Aram V. Chobanian, George L. Bakris, Henry R. Black, William C. Cushman, Lee A.

Green, Joseph L. Izzo, Jr, Daniel W. Jones, Barry J. Materson, Suzanne Oparil,

Jackson T. Wright, Jr, Edward J. Roccella and the National High Blood Pressure

Education Program Coordinating Committee

2003;42;1206-1252; originally published online Dec 1, 2003;

DOI: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2

Hypertension is published by the American Heart Association. 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX

Copyright 2003 American Heart Association. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0194-911X. Online

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Hypertension is online at

Permissions: Permissions & Rights Desk, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a division of WoltersKluwer Health, 351 West Camden Street, Baltimore, MD 21202-2436. Phone: 410-528-4050. Fax:410-528-8550. E-mail:

Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at

JNC 7 – COMPLETE VERSION

SEVENTH REPORT OF THE JOINT NATIONAL

COMMITTEE ON PREVENTION, DETECTION,

EVALUATION, AND TREATMENT OF HIGH

Aram V. Chobanian, George L. Bakris, Henry R. Black, William C. Cushman, Lee A. Green,

Joseph L. Izzo, Jr, Daniel W. Jones, Barry J. Materson, Suzanne Oparil, Jackson T. Wright, Jr,

Edward J. Roccella, and the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee

Abstract—The National High Blood Pressure Education Program presents the complete Seventh Report of the Joint

National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Like its predecessors,

the purpose is to provide an evidence-based approach to the prevention and management of hypertension. The key

messages of this report are these: in those older than age 50, systolic blood pressure (BP) of greater than 140 mm Hg

is a more important cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor than diastolic BP; beginning at 115/75 mm Hg, CVD risk

doubles for each increment of 20/10 mm Hg; those who are normotensive at 55 years of age will have a 90% lifetime

risk of developing hypertension; prehypertensive individuals (systolic BP 120 –139 mm Hg or diastolic BP 80 – 89

mm Hg) require health-promoting lifestyle modifications to prevent the progressive rise in blood pressure and CVD; for

uncomplicated hypertension, thiazide diuretic should be used in drug treatment for most, either alone or combined with

drugs from other classes; this report delineates specific high-risk conditions that are compelling indications for the use

of other antihypertensive drug classes (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers,

beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers); two or more antihypertensive medications will be required to achieve goal BP

(⬍140/90 mm Hg, or ⬍130/80 mm Hg) for patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease; for patients whose BP

is more than 20 mm Hg above the systolic BP goal or more than 10 mm Hg above the diastolic BP goal, initiation of therapy

using two agents, one of which usually will be a thiazide diuretic, should be considered; regardless of therapy or care,

hypertension will be controlled only if patients are motivated to stay on their treatment plan. Positive experiences, trust in the

clinician, and empathy improve patient motivation and satisfaction. This report serves as a guide, and the committee continues

to recognize that the responsible physician's judgment remains paramount.

(Hypertension. 2003;42:1206 –1252.)

For more than 3 decades, the National Heart, Lung, and hypertension may be as much as 1 billion individuals, and

Blood Institute (NHLBI) has administered the National

approximately 7.1 million deaths per year may be attributable

High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) Coordi-

to hypertension.3 The World Health Organization reports that

nating Committee, a coalition of 39 major professional,

suboptimal BP (⬎115 mm Hg SBP) is responsible for 62% of

public, and voluntary organizations and 7 federal agencies.

cerebrovascular disease and 49% of ischemic heart disease,

One important function is to issue guidelines and advisories

with little variation by sex. In addition, suboptimal blood

designed to increase awareness, prevention, treatment, and

pressure is the number one attributable risk for death through-

control of hypertension (high blood pressure).

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination

Considerable success has been achieved in the past in

Survey (NHANES) have indicated that 50 million or more

meeting the goals of the program. The awareness of hyper-

Americans have high blood pressure (BP) warranting some

tension has improved from a level of 51% of Americans in the

form of treatment.1,2 Worldwide prevalence estimates for

period 1976 to 1980 to 70% in 1999 to 2000 (Table 1). The

Received November 5, 2003; revision accepted November 6, 2003.

From Boston University School of Medicine (A.V.C.), Boston, Mass; Rush University Medical Center (G.L.B., H.R.B.), Chicago, Ill; Veterans Affairs

Medical Center (W.C.C.), Memphis, Tenn; University of Michigan (L.A.G.), Ann Arbor, Mich; State University of New York at Buffalo School ofMedicine (J.L.I. Jr.), Buffalo, NY; University of Mississippi Medical Center (D.W.J.), Jackson, Miss; University of Miami (B.J.M.), Miami, Fla;University of Alabama at Birmingham (S.O.), Birmingham, Ala; Case Western Reserve University (J.T.W. Jr.), Cleveland, Ohio; National Heart, Lung,and Blood Institute (E.J.R.), Bethesda, Md.

The executive committee, writing teams, and reviewers served as volunteers without remuneration.

Members of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee are listed in the Appendix.

Correspondence to Edward J. Roccella, PhD, Coordinator, National High Blood Pressure Education Program, National Heart, Lung, and Blood

Institute, National Institutes of Health, Building 31, Room 4A10, 31 Center Drive MSC 2480, Bethesda, MD 20892. E-mail

[email protected]

2003 American Heart Association, Inc.

Hypertension is available at http://www.hypertensionaha.org

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

Trends in Awareness, Treatment, and Control of

High Blood Pressure 1976 –2000

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, %

Percentage of adults aged 18 to 74 years with systolic blood pressure (SBP)

of 140 mm Hg or greater, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mm Hg orgreater, or taking antihypertensive medication.

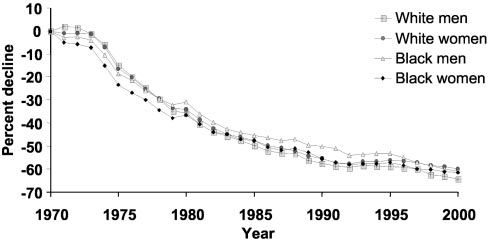

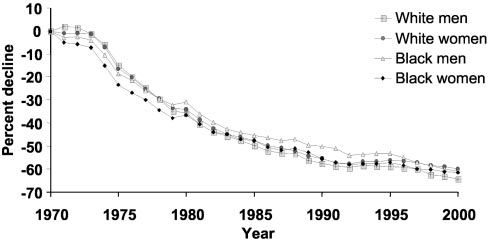

Figure 2. Percentage decline in age-adjusted mortality rates for

*SBP below 140 mm Hg and DBP below 90 mm Hg and on antihypertensive

stroke by gender and race: United States, 1970 to 2000.

Source: Prepared by T. Thom, National Heart, Lung, and BloodInstitute from Vital Statistics of the United States, National Cen-ter for Health Statistics. Death rates are age-adjusted to the

percentage of patients with hypertension receiving treatment

2000 US census population.

has increased from 31% to 59% in the same period, and thepercentage of persons with high BP controlled to below

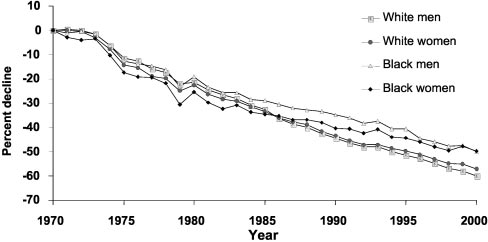

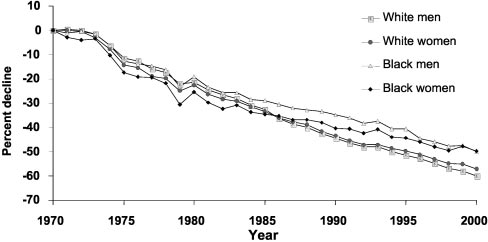

Furthermore, the rates of decline of deaths from CHD and

140/90 mm Hg has increased from 10% to 34%. Between

stroke have slowed in the past decade. In addition, the

1960 and 1991, median systolic BP (SBP) for individuals 60

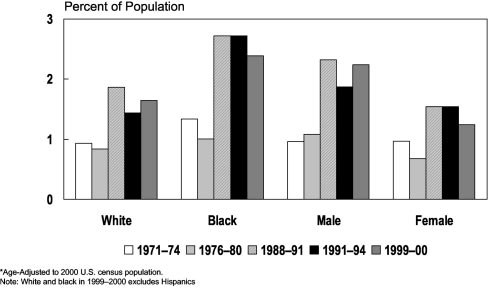

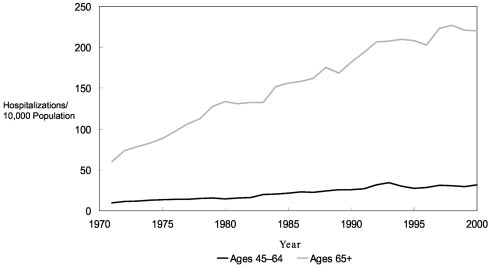

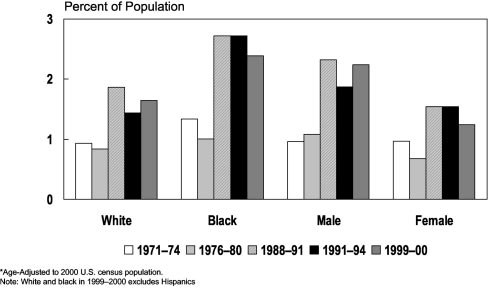

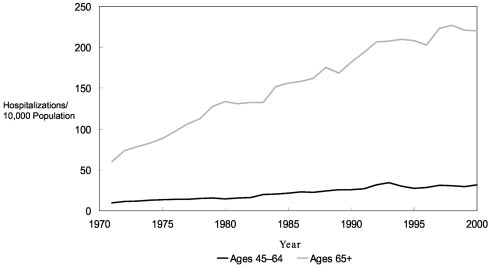

prevalence and hospitalization rates of HF, wherein the

to 74 years old declined by approximately 16 mm Hg (Figure

majority of patients have hypertension before developing

1). These changes have been associated with highly favorable

heart failure, have continued to increase (Figures 5 and 6).

trends in the morbidity and mortality attributed to hyperten-

Moreover, there is an increasing trend in end-stage renal

sion. Since 1972, age-adjusted death rates from stroke and

disease (ESRD) by primary diagnosis. Hypertension is sec-

coronary heart disease (CHD) have declined by approxi-

ond only to diabetes as the most common antecedent for this

mately 60% and 50%, respectively (Figures 2 and 3). These

condition (Figure 7). Undiagnosed, untreated, and uncon-

benefits have occurred independent of gender, age, race, or

trolled hypertension clearly places a substantial strain on the

socioeconomic status. Within the last 2 decades, better

health care delivery system.

treatment of hypertension has been associated with a consid-erable reduction in the hospital case-fatality rate for heartfailure (HF) (Figure 4). This information suggests that there

have been substantial improvements.

The decision to appoint a committee for The Seventh Report of the

However, these improvements have not been extended to

Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and

the total population. Current control rates for hypertension in

Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) was based on 4 factors:the publication of many new hypertension observational studies and

the United States are clearly unacceptable. Approximately

clinical trials since the last report was published in 19974; the need

30% of adults are still unaware of their hypertension, more

for a new clear and concise guideline that would be useful to

than 40% of individuals with hypertension are not on treat-

clinicians; the need to simplify the classification of BP; and a clear

ment, and two thirds of hypertensive patients are not being

recognition that the JNC reports did not result in maximum benefit

controlled to BP levels less than 140/90 mm Hg (Table 1).

to the public. This JNC report is presented in 2 separate publications.

The initial "Express" version, a succinct practical guide, waspublished in the May 21, 2003, issue of the Journal of the AmericanMedical Association.5 The current, more comprehensive reportprovides a broader discussion and justification for the recommenda-tions made by the committee. As with prior JNC reports, the

Figure 3. Percentage decline in age-adjusted mortality rates for

CHD by gender and race: United States, 1970 to 2000. Source:

Figure 1. Smoothed weighted frequency distribution, median,

Prepared by T. Thom, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

and 90th percentile of SBP for ages 60 to 74 years, United

from Vital Statistics of the United States, National Center for

States, 1960 to 1991. Source: Burt et al. Hypertension

Health Statistics. Death rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 US

1995;26:60 – 69. Erratum in: Hypertension 1996;27:1192.

census population.

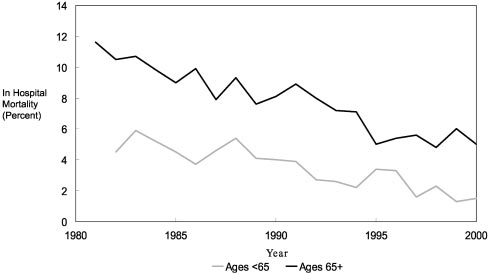

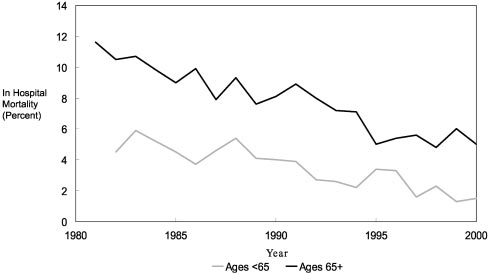

Figure 6. Hospitalization rates for congestive heart failure, ages

Figure 4. Hospital case-fatality rates for congestive heart failure,

45 to 64 and 65⫹: United States, 1971 to 2000. Source:

ages ⬍65 and 65⫹: United States, 1981 to 2000. Source:

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortal-

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortal-

ity: 2002 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Dis-

ity: 2002 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Dis-

ease. Chart 3–35. Accessed September 2003.

ease. Chart 3–36. Accessed September 2003.

appointed the JNC 7 chair and an Executive Committee derived from

committee recognizes that the responsible physician's judgment is

the Coordinating Committee membership. The Coordinating Com-

paramount in managing his or her patients.

mittee members served on 1 of 5 JNC 7 writing teams, which

Since the publication of the JNC 6 report, the NHBPEP Coordi-

contributed to the writing and review of the document.

nating Committee, chaired by the director of the NHLBI, has

The concepts for the new report identified by the NHBPEP

regularly reviewed and discussed studies on hypertension. To con-

Coordinating Committee membership were used to create the report

duct this task, the Coordinating Committee is divided into 4

outline. On the basis of these critical issues and concepts, the

subcommittees: Science Base; Long Range Planning; Professional,

Executive Committee developed relevant medical subject headings

Patient, and Public Education; and Program Organization. The

(MeSH) terms and keywords to further review the scientific litera-

subcommittees work together to review the hypertension scientific

ture. These MeSH terms were used to generate MEDLINE searches

literature from clinical trials, epidemiology, and behavioral science.

that focused on English-language, peer-reviewed scientific literature

In many instances, the principal investigator of the larger studies has

from January 1997 through April 2003. Various systems of grading

presented the information directly to the Coordinating Committee.

the evidence were considered, and the classification scheme used in

The committee reviews are summarized and posted on the NHLBI

JNC 6 and other NHBPEP clinical guidelines was selected.4,7–10 This

web site.6 This ongoing review process keeps the committee apprisedof the current state of the science, and the information is also used to

scheme classifies studies according to a process adapted from Last

develop program plans for future activities, such as continuing

and Abramson (see the section Scheme Used for Classification of the

During fall 2002, the NHBPEP Coordinating Committee chair

In reviewing the exceptionally large body of research literature in

solicited opinions regarding the need to update the JNC 6 report. The

hypertension, the Executive Committee focused its deliberations on

entire Coordinating Committee membership provided, in writing, adetailed rationale explaining the necessity for updating JNC 6,outlined critical issues, and provided concepts to be addressed in thenew report. Thereafter, the NHBPEP Coordinating Committee chair

Figure 5. Prevalence of CHF by race and gender, ages 25 to

74: United States, 1971 to 1974 to 1999 to 2000. Age-adjusted

to 2000 US census population. White and African American in

1999 to 2000 excludes Hispanics. Source: National Heart, Lung,

and Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortality: 2002 Chart Book

on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Disease. Accessed Sep-

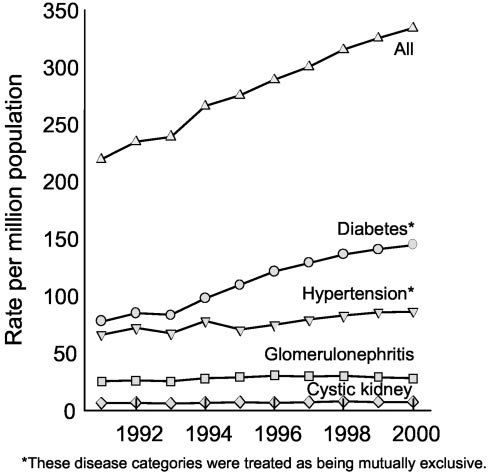

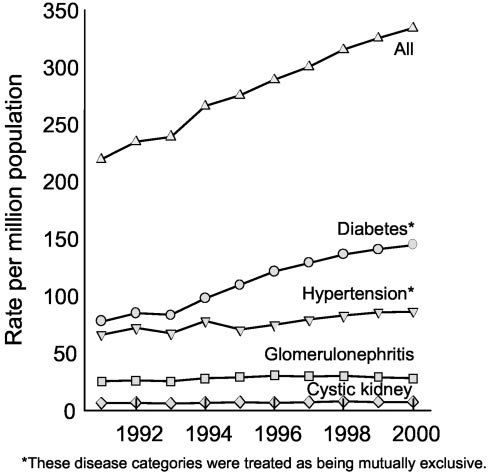

Figure 7. Trends in incident rates of ESRD, by primary diagno-

sis (adjusted for age, gender, race). Disease categories were

book.htm and 1999 to 2000 unpublished data computed by M.

treated as being mutually exclusive. Source: United States

Wolz and T. Thom, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Renal Data System. 2002. Figure 1.14. Accessed September,

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

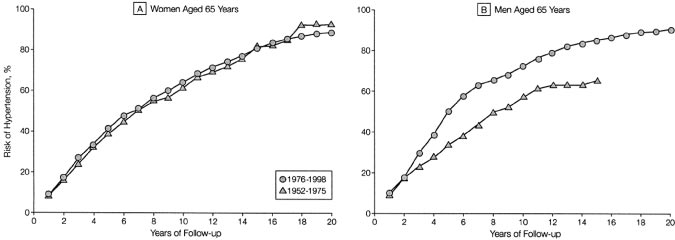

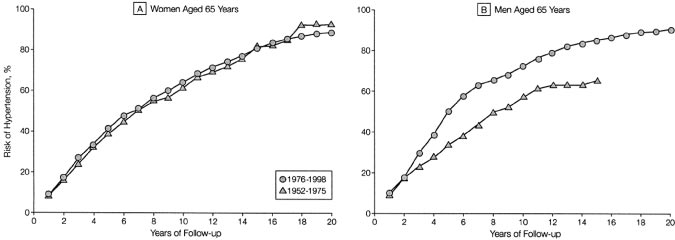

Figure 8. Residual lifetime risk of hyper-

tension in women and men aged 65

years. Cumulative incidence of hyperten-

sion in 65-year-old women and men.

Data for 65-year-old men in the 1952 to

1975 period are truncated at 15 years

since there were few participants in this

age category who were followed up

beyond this time interval. Source: JAMA

2002;287:1003–1010. Copyright 2002,

American Medical Association. All rights

reserved.

evidence pertaining to outcomes of importance to patients and with

circulated among the Coordinating Committee members for review and

effects of sufficient magnitude to warrant changes in medical

comment. The JNC 7 chair synthesized the comments, and the longer

practice ("patient oriented evidence that matters" [POEMs]).12,13

version was submitted to the journal Hypertension in November, 2003.

Patient-oriented outcomes include not only mortality but also otheroutcomes that affect patients' lives and well-being, such as sexual

Lifetime Risk of Hypertension

function, ability to maintain family and social roles, ability to work,

Hypertension is an increasingly important medical and public

and ability to carry out activities of daily living. These outcomes are

health issue. The prevalence of hypertension increases with

strongly affected by nonfatal stroke, HF, coronary heart disease, and

advancing age to the point where more than half of people

renal disease; hence, these outcomes were considered along withmortality in the committee's evidence-based deliberations. Studies of

aged 60 to 69 years old and approximately three-fourths of

physiological end points (disease-oriented evidence [DOEs]) were

those aged 70 years and older are affected.1 The age-related

used to address questions where POEMs were not available.

rise in SBP is primarily responsible for an increase in both

The Coordinating Committee began the process of developing the

incidence and prevalence of hypertension with increasing

JNC 7 Express report in December 2002, and the report was

submitted to the Journal of the American Medical Association inApril 2003. It was published in an electronic format on May 14,

Whereas the short-term absolute risk for hypertension is

2003, and in print on May 21, 2003. During this time, the Executive

conveyed effectively by incidence rates, the long-term risk is

Committee met on 6 occasions, 2 of which included meetings with

best summarized by the lifetime risk statistic, which is the

the entire Coordinating Committee. The writing teams also met by

probability of developing hypertension during the remaining

teleconference and used electronic communications to develop the

years of life (either adjusted or unadjusted for competing

report. Twenty-four drafts were created and reviewed repeatedly. At

causes of death). Framingham Heart Study investigators

its meetings, the Executive Committee used a modified nominalgroup process14 to identify and resolve issues. The NHBPEP

recently reported the lifetime risk of hypertension to be

Coordinating Committee reviewed the penultimate draft and pro-

approximately 90% for men and women who were nonhy-

vided written comments to the Executive Committee. In addition, 33

pertensive at 55 or 65 years old and survived to age 80 to 85

national hypertension leaders reviewed and commented on the

(Figure 8).16 Even after adjusting for competing mortality, the

document. The NHBPEP Coordinating Committee approved the

remaining lifetime risks of hypertension were 86 to 90% in

JNC 7 Express report. To complete the longer JNC 7 version, theExecutive Committee members met via teleconferences and in

women and 81 to 83% in men.

person and circulated sections of the larger document via e-mail. The

The impressive increase of BP to hypertensive levels with

sections were assembled and edited by the JNC 7 chair and were

age is also illustrated by data indicating that the 4-year rates

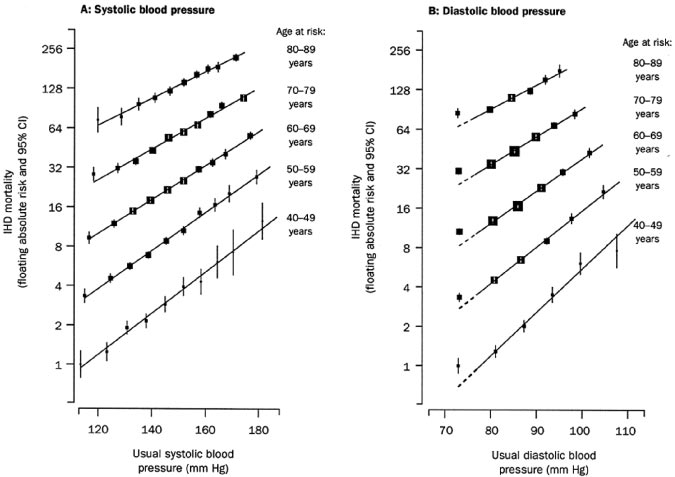

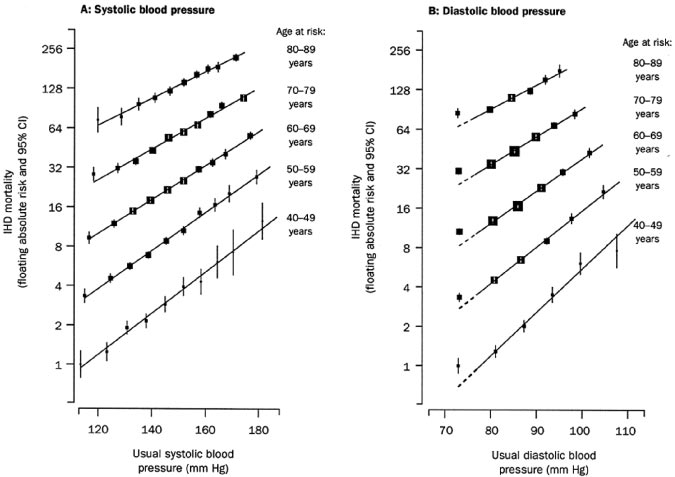

Figure 9. Ischemic heart disease (IHD)

mortality rate in each decade of age ver-

sus usual blood pressure at the start of

that decade. Source: Reprinted with per-

mission from Elsevier (The Lancet,

2002;360:1903–1913).

Figure 10. Stroke mortality rate in each

decade of age versus usual blood pres-

sure at the start of that decade. Source:

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier

(The Lancet, 2002;360:1903–1913).

of progression to hypertension are 50% for those 65 years and

In addition, longitudinal data obtained from the Framing-

older with BP in the 130 to 139/85 to 89 mm Hg range and

ham Heart Study have indicated that BP values in the 130 to

26% for those with BP in the 120 to 129/80 to 84 mm Hg

139/85 to 89 mm Hg range are associated with a more than

2-fold increase in relative risk from cardiovascular disease(CVD) compared with those with BP levels below 120/

Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Risk

80 mm Hg (Figure 11).19

Data from observational studies involving more than 1million individuals have indicated that death from bothischemic heart disease and stroke increases progressively and

Basis for Reclassification of Blood Pressure

linearly from BP levels as low as 115 mm Hg systolic and

Because of the new data on lifetime risk of hypertension and

75 mm Hg diastolic upward (Figures 9 and 10).18 The

the impressive increase in the risk of cardiovascular compli-

increased risks are present in all age groups ranging from 40

cations associated with levels of BP previously considered to

to 89 years old. For every 20 mm Hg systolic or 10 mm Hg

be normal, the JNC 7 report has introduced a new classifica-

diastolic increase in BP, there is a doubling of mortality from

tion that includes the term "prehypertension" for those with

both ischemic heart disease and stroke.

BPs ranging from 120 to 139 mm Hg systolic and/or 80 to

Figure 11. Impact of high normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events

in women (A) and men (B) without hypertension, according to blood-pressure category at the baseline examination. Vertical bars indi-

cate 95% confidence intervals. Optimal BP is defined here as a systolic pressure of less than 120 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure of

less than 80 mm Hg. Normal BP is a systolic pressure of 120 to 129 mm Hg or a diastolic pressure of 80 to 84 mm Hg. High-normal

BP is a systolic pressure of 130 to 139 mm Hg or a diastolic pressure of 85 to 89 mm Hg. If the systolic and diastolic pressure read-

ings for a subject were in different categories, the higher of the two categories was used. Source: N Engl J Med 2001;345:1291–1297.

Copyright 2001, Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

Figure 12. Ten-year risk for CHD by SBP and presence of other

risk factors. Source: Derived from K.M. Anderson, P.W.F. Wil-

son, P.M. Odell, W.B. Kannel. An updated coronary risk profile.

A statement for health professionals. Circulation

1991;83:356 –362.

for individuals with hypertension and no other compelling

89 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure (DBP). This new desig-

conditions is ⬍140/90 mm Hg (see the section Compelling

nation is intended to identify those individuals in whom early

Indications). The goal for individuals with prehypertension

intervention by adoption of healthy lifestyles could reduce

and no compelling indications is to lower BP to normal with

BP, decrease the rate of progression of BP to hypertensive

lifestyle changes and prevent the progressive rise in BP using

levels with age, or prevent hypertension entirely.

the recommended lifestyle modifications (See the section

Another change in classification from JNC 6 is the combining

of stage 2 and stage 3 hypertension into a single stage 2 category.

This revision reflects the fact that the approach to the manage-

Cardiovascular Disease Risk

ment of the former two groups is similar (Table 2).

The relationship between BP and risk of CVD events iscontinuous, consistent, and independent of other risk factors.

Classification of Blood Pressure

The higher the BP, the greater is the chance of heart attack,

Table 3 provides a classification of BP for adults aged 18 and

HF, stroke, and kidney diseases. The presence of each

older. The classification is based on the average of 2 or more

additional risk factor compounds the risk from hypertension,

properly measured, seated BP readings on each of 2 or more

as illustrated in Figure 12.20 The easy and rapid calculation of

office visits.

a Framingham CHD risk score using published tables21 may

Prehypertension is not a disease category. Rather it is a

assist the clinician and patient in demonstrating the benefits

designation chosen to identify individuals at high risk of

of treatment. Management of these other risk factors is

developing hypertension, so that both patients and clinicians

essential and should follow the established guidelines for

are alerted to this risk and encouraged to intervene and

controlling these coexisting problems that contribute to over-

prevent or delay the disease from developing. Individuals

all cardiovascular risk.

who are prehypertensive are not candidates for drug therapyon the basis of their level of BP and should be firmly and

Importance of Systolic Blood Pressure

unambiguously advised to practice lifestyle modification in

Impressive evidence has accumulated to warrant greater

order to reduce their risk of developing hypertension in the

attention to the importance of SBP as a major risk factor for

future (see the section Lifestyle Modifications). Moreover,individuals with prehypertension who also have diabetes orkidney disease should be considered candidates for appropri-ate drug therapy if a trial of lifestyle modification fails toreduce their BP to 130/80 mm Hg or less.

This classification does not stratify hypertensives by the

presence or absence of risk factors or target organ damage inorder to make different treatment recommendations, if eitheror both are present. JNC 7 suggests that all people withhypertension (Stages 1 and 2) be treated. The treatment goal

Classification of Blood Pressure for Adults

BP Classification

Figure 13. Changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure with

age. SBP and DBP by age and race or ethnicity for men and

Stage 1 hypertension

women over 18 years of age in the US population. Data fromNHANES III, 1988 to 1991. Source: Burt VL et al. Hypertension

Stage 2 hypertension

Figure 14. Difference in CHD prediction between systolic and

diastolic blood pressure as a function of age. The strength of

the relationship as a function of age is indicated by an increase

in the  coefficient. Difference in  coefficients (from Cox

Figure 15. Systolic blood pressure distributions. Source: Whel-

proportional-hazards regression) between SBP and DBP is plot-

ton PK et al. JAMA 2002;288:1884.

ted as function of age, obtaining this regression line:  (SBP)⫺(DBP)⫽1.4948⫹0.0290 ⫻ age (P⫽0.008). A  coefficient level

BP with age could be prevented or diminished, much of

⬍0.0 indicates a stronger effect of DBP on CHD risk, while lev-els ⬎0.0 suggest a greater importance of systolic pressure.

hypertension, cardiovascular and renal disease, and stroke

Source: Circulation 2001;103:1247.

might be prevented. A number of important causal factors forhypertension have been identified, including excess body

CVDs. Changing patterns of BP occur with increasing age.

weight; excess dietary sodium intake; reduced physical ac-

The rise in SBP continues throughout life, in contrast to DBP,

tivity; inadequate intake of fruits, vegetables, and potassium;

which rises until approximately 50 years old, tends to level

and excess alcohol intake.10,32 The prevalence of these char-

off over the next decade, and may remain the same or fall

acteristics is high. One hundred twenty-two million Ameri-

later in life (Figure 13).1,15 Diastolic hypertension predomi-

cans are overweight or obese.33 Mean sodium intake is

nates before 50 years of age, either alone or in combination

approximately 4100 mg per day for men and 2750 mg per day

with SBP elevation. The prevalence of systolic hypertension

for women, 75% of which comes from processed foods.34,35

increases with age, and above the age of 50 years, systolic

Fewer than 20% of Americans engage in regular physical

hypertension represents the most common form of hyperten-

activity,36 and fewer than 25% consume 5 or more servings of

sion. DBP is a more potent cardiovascular risk factor than

fruits and vegetables daily.37

SBP until age 50; thereafter, SBP is more important (Figure

Because the lifetime risk of developing hypertension is

very high (Figure 8), a public health strategy that comple-

Clinical trials have demonstrated that control of isolated

ments the hypertension treatment strategy is warranted. In

systolic hypertension reduces total mortality, cardiovascular

order to prevent BP levels from rising, primary prevention

mortality, stroke, and HF events.23–25 Both observational

measures should be introduced to reduce or minimize these

studies and clinical trial data suggest that poor SBP control is

causal factors in the population, particularly in individuals

largely responsible for the unacceptably low rates of overall

with prehypertension. A population approach that decreases

BP control.26,27 In the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering

the BP level in the general population by even modest

Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) andControlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular

amounts has the potential to substantially reduce morbidity

End Points (CONVINCE) trial, DBP control rates exceeded

and mortality or at least delay the onset of hypertension. For

90%, but SBP control rates were considerably less (60 to

example, it has been estimated that a 5 mm Hg reduction of

70%).28,29 Poor SBP control is at least in part related to

SBP in the population would result in a 14% overall reduction

physician attitudes. A survey of primary care physicians

in mortality due to stroke, a 9% reduction in mortality due to

indicated that three-fourths of them failed to initiate antihy-

CHD, and a 7% decrease in all-cause mortality (Figure

pertensive therapy in older individuals with SBP of 140 to

159 mm Hg, and most primary care physicians did not pursue

Barriers to prevention include cultural norms; insufficient

control to less than 140 mm Hg.30,31 Most physicians have

attention to health education by health care practitioners; lack

been taught that the diastolic pressure is more important than

of reimbursement for health education services; lack of

SBP and thus treat accordingly. Greater emphasis must

access to places to engage in physical activity; larger servings

clearly be placed on managing systolic hypertension. Other-

of food in restaurants; lack of availability of healthy food

wise, as the US population becomes older, the toll of

choices in many schools, worksites, and restaurants; lack of

uncontrolled SBP will cause increased rates of cardiovascular

exercise programs in schools; large amounts of sodium added

and renal diseases.

to foods by the food industry and restaurants; and the highercost of food products that are lower in sodium and calories.10

Prevention of Hypertension: Public

Overcoming the barriers will require a multipronged ap-

proach directed not only to high-risk populations but also to

The prevention and management of hypertension are major

communities, schools, worksites, and the food industry. The

public health challenges for the United States. If the rise in

recent recommendations by the American Public Health

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

Association and the NHBPEP Coordinating Committee that

Recommendations for Follow-Up Based on Initial

the food industry, including manufacturers and restaurants,

Blood Pressure Measurements for Adults Without Acute End

reduce sodium in the food supply by 50% over the next

Organ Damage

decade is the type of approach that, if implemented, would

reduce BP in the population.39,40

Follow-Up Recommended†

Recheck in 2 years

Recheck in 1 year‡

Healthy People 2010 has identified the community as asignificant partner and vital point of intervention for attaining

Stage 1 hypertension

Confirm within 2 months‡

healthy goals and outcomes.41 Partnerships with community

Stage 2 hypertension

Evaluate or refer to source of care within 1 month.

groups such as civic, philanthropic, religious, and senior

For those with higher pressures (eg,⬎180/110 mm Hg), evaluate and treat immediately

citizen organizations provide locally focused orientation to

or within 1 week depending on clinical situation

the health needs of diverse populations. The probability of

and complications.

success increases as interventional strategies more aptly

*If systolic and diastolic categories are different, follow recommendations for

address the diversity of racial, ethnic, cultural, linguistic,

shorter time follow-up (e.g., 160/86 mm Hg should be evaluated or referred to

religious, and social factors in the delivery of medical

source of care within 1 month).

services. Community service organizations can promote the

†Modify the scheduling of follow-up according to reliable information about past

prevention of hypertension by providing culturally sensitive

BP measurements, other cardiovascular risk factors, or target organ disease.

educational messages and lifestyle support services and by

‡Provide advice about lifestyle modifications (see Lifestyle Modifications

establishing cardiovascular risk factor screening and referralprograms. Community-based strategies and programs have

should be avoided for at least 30 minutes prior to measure-

been addressed in prior NHLBI publications and other doc-uments (Facts About the DASH Eating Plan,

ment. Measurement of BP in the standing position is indi-

Lowering High Blood Pressure,43 National High Blood Pres-

cated periodically, especially in those at risk for postural

sure Education Month,44 The Heart Truth: A National Aware-

hypotension, prior to necessary drug dose or adding a drug,

ness Campaign for Women About Heart Disease,45 Mobiliz-

and in those who report symptoms consistent with reduced

ing African American Communities To Address Disparities in

BP on standing. An appropriately sized cuff (cuff bladder

Cardiovascular Health: The Baltimore City Health Partner-

encircling at least 80% of the arm) should be used to ensure

ship Strategy Development Workshop Summary Report,46

accuracy. At least two measurements should be made and the

NHLBI Healthy People 2010 Gateway,47 Cardiovascular

average recorded. For manual determinations, palpated radial

Disease Enhanced Dissemination and Utilization Centers

pulse obliteration pressure should be used to estimate SBP;

[EDUCs] Awardees,48 Hearts N' Parks,49 Healthbeat Radio

the cuff should then be inflated 20 to 30 mm Hg above this

Network,50 Salud para su Corazo´n [For the Health of Your

level for the auscultatory determinations; the cuff deflation

rate for auscultatory readings should be 2 mm Hg per second.

SBP is the point at which the first of two or more Korotkoff

Calibration, Maintenance, and Use of Blood

sounds is heard (onset of phase 1), and the disappearance of

Korotkoff sound (onset of phase 5) is used to define DBP.

The potential of mercury spillage contaminating the environ-

Clinicians should provide to patients, verbally and in writing,

ment has led to the decreased use or elimination of mercury

their specific BP numbers and the BP goal of their treatment.

in sphygmomanometers as well as in thermometers52 How-

Follow-up of patients with various stages of hypertension

ever, concerns regarding the accuracy of nonmercury sphyg-

is recommended as shown in Table 4.

momanometers have created new challenges for accurate BPdetermination.53,54 When mercury sphygmomanometers are

Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring

replaced, the new equipment, including all home BP mea-

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) provides

surement devices, must be appropriately validated and

information about BP during daily activities and sleep.59 BP

checked regularly for accuracy.55

has a reproducible circadian profile, with higher values whileawake and mentally and physically active, much lower values

Accurate Blood Pressure Measurement in

during rest and sleep, and early morning increases for 3 or

the Office

more hours during the transition of sleep to wakefulness.60

The accurate measurement of BP is the sine qua non for

These devices use either a microphone to measure Korotkoff

successful management. The equipment, whether aneroid,

sounds or a cuff that senses arterial waves using oscillometric

mercury, or electronic, should be regularly inspected and

techniques. Twenty-four-hour BP monitoring provides mul-

validated. The operator should be trained and regularly

tiple readings during all of a patient's activities. While office

retrained in the standardized technique, and the patient must

BP values have been used in the numerous studies that have

be properly prepared and positioned.4,56,57 The auscultatory

established the risks associated with an elevated BP and the

method of BP measurement should be used.58 Persons should

benefits of lowering BP, office measurements have some

be seated quietly for at least 5 minutes in a chair (rather than

shortcomings. For example, a white-coat effect (increase in

on an examination table), with feet on the floor, and arm

BP primarily in the medical care environment) is noted in as

supported at heart level. Caffeine, exercise, and smoking

many as 20 to 35% of patients diagnosed with hypertension.61

Clinical Situations in Which Ambulatory Blood

Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Pressure Monitoring May Be Helpful

Major risk factors

Suspected white-coat hypertension in patients with hypertension and no

target organ damage

Age (older than 55 for men, 65 for women)†

Apparent drug resistance (office resistance)

Diabetes mellitus*

Hypotensive symptoms with antihypertensive medication

Elevated LDL (or total) cholesterol or low HDL cholesterol*

Episodic hypertension

Estimated GFR ⬍60 mL/min

Autonomic dysfunction

Family history of premature cardiovascular disease (men aged ⬍55 orwomen aged ⬍65)

Ambulatory BP values are usually lower than clinic read-

ings. Awake hypertensive individuals have an average BP of

Obesity* (body mass index ⱖ30 kg/m2)

⬎135/85 mm Hg and during sleep, ⬎120/75 mm Hg. The

Physical inactivity

level of BP measurement using ABPM correlates better than

Tobacco usage, particularly cigarettes

office measurements with target organ injury.15 ABPM also

Target organ damage

provides a measure of the percentage of BP readings that areelevated, the overall BP load, and the extent of BP fall during

sleep. In most people, BP drops by 10 to 20% during the night;

Left ventricular hypertrophy

those in whom such reductions are not present appear to be at

Angina/prior myocardial infarction

increased risk for cardiovascular events. In addition, it was

Prior coronary revascularization

reported recently that ABPM patients whose 24-hour BP ex-

ceeded 135/85 mm Hg were nearly twice as likely to have a

cardiovascular event as those with 24-hour mean BPs less than

Stroke or transient ischemic attack

135/85 mm Hg, irrespective of the level of the office BP.62,63

Indications for the use of ABPM are listed in Table 5.

Medicare reimbursement for ABPM is now provided to

Chronic kidney disease

assess patients with suspected white-coat hypertension.

Peripheral arterial disease

GFR indicates glomerular filtration rate.

Self-monitoring of BP at home and work is a practical

*Components of the metabolic syndrome. Reduced HDL and elevated

approach to assess differences between office and out-of-

triglycerides are components of the metabolic syndrome. Abdominal obesity is

office BP prior to consideration of ambulatory monitoring.

also a component of metabolic syndrome.

For those whose out-of-office BPs are consistently ⬍130/

†Increased risk begins at approximately 55 and 65 for men and women,

respectively. Adult Treatment Panel III used earlier age cutpoints to suggest the

80 mm Hg despite an elevated office BP and who lack

need for earlier action.

evidence of target organ disease, 24-hour monitoring or drugtherapy can be avoided.

Self-measurement or ambulatory monitoring may be par-

extremities for edema and pulses; and neurological

ticularly helpful in assessing BP in smokers. Smoking raises

BP acutely, and the level returns to baseline in about 15

Data from epidemiological studies and clinical trials have

minutes after stopping.

demonstrated that elevations in resting heart rate and reducedheart rate variability are associated with higher cardiovascu-

lar risk. In the Framingham Heart Study, an average resting

Evaluation of hypertensive patients has three objectives: (1)

heart rate of 83 beats per minute was associated with a

to assess lifestyle and identify other cardiovascular risk

substantially higher risk of death from a CV event than those

factors or concomitant disorders that may affect prognosisand guide treatment (Table 6); (2) to reveal identifiable

Identifiable Causes of Hypertension

causes of high BP (Table 7); and (3) to assess the presence or

Chronic kidney disease

absence of target organ damage and CVD.

Patient evaluation is made through medical history, phys-

Coarctation of the aorta

ical examination, routine laboratory tests, and other diagnos-

Cushing syndrome and other glucocorticoid excess states including chronic

tic procedures. The physical examination should include an

appropriate measurement of BP, with verification in the

Drug-induced or drug-related (see Table 18)

contralateral arm; examination of the optic fundi; calculation

Obstructive uropathy

of body mass index (BMI) (measurement of waist circumfer-

ence is also very useful); auscultation for carotid, abdominal,

Primary aldosteronism and other mineralocorticoid excess states

and femoral bruits; palpation of the thyroid gland; thorough

examination of the heart and lungs; examination of the

abdomen for enlarged kidneys, masses, distended urinary

Thyroid or parathyroid disease

bladder, and abnormal aortic pulsation; palpation of the lower

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

Screening Tests for Identifiable Hypertension

Chronic kidney disease

Coarctation of the aorta

Cushing syndrome and other glucocorticoid

History/dexamethasone suppression test

excess states including chronic steroid therapy

Drug-induced/related (see Table 18)

History; drug screening

24-hour urinary metanephrine and normetanephrine

Primary aldosteronism and other

24-hour urinary aldosterone level or specific

mineralocorticoid excess states

measurements of other mineralocorticoids

Doppler flow study; magnetic resonance angiography

Sleep study with O2 saturation

GFR indicates glomerular filtration rate; CT, computed tomography; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; PTH,

at lower heart rate levels.64 Moreover, reduced heart rate

be considered in some individuals, particularly those with

variability was also associated with an increase in CV

CVD but without other risk factor abnormalities. Results of

mortality.65 No clinical trials have prospectively evaluated the

an analysis of the Framingham Heart Study cohort demon-

impact of reducing heart rate on CV outcomes.

strated that those with an LDL value within the rangeassociated with low CV risk, who also had an elevated

Laboratory Tests and Other

HS-CRP value, had a higher CV event rate as compared with

those with low CRP and high LDL-C.73 Other studies also

Routine laboratory tests recommended before initiating ther-

have shown that elevated CRP is associated with a higher CV

apy include a 12-lead ECG; urinalysis; blood glucose and

event rate, especially in women.74 Elevations in homocys-

hematocrit; serum potassium, creatinine (or the correspond-

teine have also been described as associated with higher CV

ing estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]), and calci-

risk; however, the results with this marker are not as robust as

um66; and a lipoprotein profile (after 9- to 12-hour fast) that

those with high HS-CRP.75,76

includes HDL and LDL cholesterol (HDL-C and LDL-C) andtriglycerides (TGs). Optional tests include measurement of

Identifiable Causes of Hypertension

urinary albumin excretion or albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR),

Additional diagnostic procedures may be indicated to identify

except for those with diabetes or kidney disease, for whom

causes of hypertension, particularly in patients whose (1) age,

annual measurements should be made. More extensive testing

history, physical examination, severity of hypertension, or

for identifiable causes is not indicated generally unless BP

initial laboratory findings suggest such causes; (2) BP re-

control is not achieved or the clinical and routine laboratory

sponds poorly to drug therapy; (3) BP begins to increase for

evaluation strongly suggests an identifiable secondary cause

uncertain reason after being well controlled; and (4) onset of

(ie, vascular bruits, symptoms of catecholamine excess,

hypertension is sudden. Screening tests for particular forms of

unprovoked hypokalemia). See the section Identifiable

identifiable hypertension are shown in Table 8.

Causes of Hypertension for a more thorough discussion.

Pheochromocytoma should be suspected in patients with

The presence of decreased GFR or albuminuria has prog-

labile hypertension or with paroxysms of hypertension ac-

nostic implications as well. Studies reveal a strong relation-

companied by headache, palpitations, pallor, and perspira-

ship between decreases in GFR and increases in cardiovas-

tion.77 Decreased pressure in the lower extremities or delayed

cular morbidity and mortality.67,68 Even small decreases in

or absent femoral arterial pulses may indicate aortic coarcta-

GFR increase cardiovascular risk.67 Serum creatinine may

tion; truncal obesity, glucose intolerance, and purple striae

overestimate glomerular filtration. The optimal tests to deter-

suggest Cushing syndrome. Examples of clues from the

mine GFR are debated, but calculating GFR from the recent

laboratory tests include unprovoked hypokalemia (primary

modifications of the Cockcroft and Gault equations is

aldosteronism), hypercalcemia (hyperparathyroidism), and

elevated creatinine or abnormal urinalysis (renal parenchymal

The presence of albuminuria, including microalbuminuria,

disease). Appropriate investigations should be conducted

even in the setting of normal GFR, is also associated with an

when there is a high index of suspicion of an identifiable

increase in cardiovascular risk.70–72 Urinary albumin excre-

tion should be quantitated and monitored on an annual basis

The most common parenchymal kidney diseases associated

in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes or renal

with hypertension are chronic glomerulonephritis, polycystic

kidney disease, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. These can

Additionally, three emerging risk factors—(1) high-

generally be distinguished by the clinical setting and addi-

sensitivity C-reactive protein (HS-CRP), a marker of inflam-

tional testing. For example, a renal ultrasound is useful in

mation; (2) homocysteine; and (3) elevated heart rate—may

diagnosing polycystic kidney disease. Renal artery stenosis

and subsequent renovascular hypertension should be sus-

drug doses, or appropriate drug combinations may result in

pected in a number of circumstances, including (1) onset of

inadequate BP control.

hypertension before 30 years of age, especially in the absenceof family history, or onset of significant hypertension after

Goals of Therapy

age 55; (2) an abdominal bruit, especially if a diastolic

The ultimate public health goal of antihypertensive therapy is

component is present; (3) accelerated hypertension; (4) hy-

to reduce cardiovascular and renal morbidity and mortality.

pertension that had been easy to control but is now resistant;

Since most persons with hypertension, especially those ⬎50

(5) recurrent flash pulmonary edema; (6) renal failure of

years old, will reach the DBP goal once the SBP goal is

uncertain etiology, especially in the absence of proteinuria or

achieved, the primary focus should be on attaining the SBP

an abnormal urine sediment; and (7) acute renal failure

goal. Treating SBP and DBP to targets that are ⬍140/

precipitated by therapy with an angiotensin-converting en-

90 mm Hg is associated with a decrease in CVD complica-tions.87 In patients with hypertension and diabetes or renal

zyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

disease, the BP goal is ⬍130/80 mm Hg.88,89

under conditions of occult bilateral renal artery stenosis ormoderate to severe volume depletion.

Benefits of Lowering Blood Pressure

In patients with suspected renovascular hypertension, non-

In clinical trials, antihypertensive therapy has been associated

invasive screening tests include the ACEI-enhanced renal

with reductions in stroke incidence averaging 35% to 40%;

scan, duplex Doppler flow studies, and magnetic resonance

myocardial infarction, 20% to 25%; and HF, ⬎50%.90 It is

angiography. While renal artery angiography remains the

estimated that in patients with stage 1 hypertension (SBP 140

gold standard for identifying the anatomy of the renal artery,

to 159 mm Hg and/or DBP 90 to 99 mm Hg) and additional

it is not recommended for diagnosis alone because of the risk

cardiovascular risk factors, achieving a sustained 12 mm Hg

associated with the procedure. At the time of intervention, an

reduction in SBP over 10 years will prevent 1 death for every

arteriogram will be performed using limited contrast to

11 patients treated. In the added presence of CVD or target

confirm the stenosis and identify the anatomy of the renal

organ damage, only 9 patients would require such BP

reduction to prevent 1 death.91

Genetics of Hypertension

The investigation of rare genetic disorders affecting BP has

Adoption of healthy lifestyles by all persons is critical for the

led to the identification of genetic abnormalities associated

prevention of high BP and is an indispensable part of the

with several rare forms of hypertension, including

management of those with hypertension.10 Weight loss of as

little as 10 lbs (4.5 kg) reduces BP and/or prevents hyperten-

hydroxylase and 17␣-hydroxylase deficiencies, Liddle syn-

sion in a large proportion of overweight persons, although the

drome, the syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess,

ideal is to maintain normal body weight.92,93 BP is also

and pseudohypoaldosteronism type II.82 The individual and

benefited by adoption of the Dietary Approaches to Stop

joint contributions of these genetic mutations to BP levels in

Hypertension (DASH) eating plan,94 which is a diet rich in

the general population, however, are very small. Genetic

fruits, vegetables, and lowfat dairy products with a reduced

association studies have identified polymorphisms in several

content of dietary cholesterol as well as saturated and total fat

candidate genes (eg, angiotensinogen, ␣-adducin, - and

(modification of whole diet). It is rich in potassium and

DA-adrenergic receptors, -3 subunit of G proteins), and

calcium content.95 Dietary sodium should be reduced to no

genetic linkage studies have focused attention on several

more than 100 mmol per day (2.4 g of sodium).94–96 Everyone

genomic sites that may harbor other genes contributing to

who is able should engage in regular aerobic physical activity

primary hypertension.83–85 However, none of these various

such as brisk walking at least 30 minutes per day most days

genetic abnormalities has been shown, either alone or in joint

of the week.97,98 Alcohol intake should be limited to no more

combination, to be responsible for any applicable portion of

than 1 oz (30 mL) of ethanol, the equivalent of two drinks, per

hypertension in the general population.

day in most men and no more than 0.5 oz of ethanol (onedrink) per day in women and lighter weight persons. A drink

is 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, and 1.5 oz of 80-proof liquor(Table 9).99 Lifestyle modifications reduce BP, prevent or

Blood Pressure Control Rates

delay the incidence of hypertension, enhance antihyperten-

Hypertension is the most common primary diagnosis in

sive drug efficacy, and decrease cardiovascular risk. For

America (35 million office visits as the primary diagnosis).5

example, in some individuals, a 1600 mg sodium DASH

Current control rates (SBP ⬍140 mm Hg and DBP

eating plan has BP effects similar to single drug therapy.94

⬍90 mm Hg), though improved, are still far below the

Combinations of 2 (or more) lifestyle modifications can

Healthy People goal of 50% (originally set as the year 2000

achieve even better results.100 For overall cardiovascular risk

goal and since extended to 2010; Table 1). In the majority of

reduction, patients should be strongly counseled to quit

patients, reducing SBP has been considerably more difficult

than lowering DBP. Although effective BP control can beachieved in most patients who are hypertensive, the majority

will require 2 or more antihypertensive drugs.28,29,86 Failure to

A large number of drugs are currently available for reducing

prescribe lifestyle modifications, adequate antihypertensive

BP. Tables 10 and 11 provide a list of the commonly used

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

Lifestyle Modifications To Prevent and Manage Hypertension*

Approximate SBP Reduction

Maintain normal body weight (body

5–20 mm Hg/10 kg92,93

mass index 18.5–24.9 kg/m2).

Adopt DASH eating plan

Consume a diet rich in fruits,

8–14 mm Hg94,95

vegetables, and low-fat dairyproducts with a reduced content ofsaturated and total fat.

Dietary sodium reduction

Reduce dietary sodium intake to no

2–8 mm Hg94–96

more than 100 mmol per day (2.4 gsodium or 6 g sodium chloride).

Physical activity

Engage in regular aerobic physical

activity such as brisk walking (atleast 30 minutes per day, most daysof the week).

Moderation of alcohol

Limit consumption to no more than 2

drinks (eg, 24 oz beer, 10 oz wine,or 3 oz 80-proof whiskey) per day inmost men and to no more than 1drink per day in women and lighter-weight persons.

DASH indicates Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

*For overall cardiovascular risk reduction, stop smoking.

†The effects of implementing these modifications are dose- and time-dependent and could be

greater for some individuals.

antihypertensive agents and their usual dose range and

disease (EUROPA), in which the ACEI perindopril was

frequency of administration.

added to existent therapy in patients with stable coronary

More than two-thirds of hypertensive individuals cannot

disease and without HF, also demonstrated reduction in CVD

be controlled on one drug and will require two or more

events with ACEIs.114

antihypertensive agents selected from different drug class-

Since 1998, several large trials comparing newer classes of

es.28,87,101–103 For example, in ALLHAT, 60% of those

agents, including CCBs, ACEIs, an ␣1 receptor blocker, and

whose BP was controlled to ⬍140/90 mm Hg received two

an ARB, with the older diuretics and/or BBs have been

or more agents, and only 30% overall were controlled on

completed.101,102,109,112,115–118 Most of these studies showed

one drug.28 In hypertensive patients with lower BP goals or

the newer classes were neither superior nor inferior to the

with substantially elevated BP, 3 or more antihypertensive

older ones. One exception was the Losartan Intervention for

drugs may be required.

Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study, in which

Since the first VA Cooperative trial published in 1967,

CVD events were 13% lower (because of differences in

thiazide-type diuretics have been the basis of antihyperten-

stroke but not CHD rates) with the ARB losartan than with

sive therapy in the majority of placebo-controlled outcome

the BB atenolol.102 There has not been a large outcome trial

trials in which CVD events, including strokes, CHD, and HF,

completed as yet comparing an ARB with a diuretic. All of

have been reduced by BP lowering.104–108 However, there are

these trials taken together suggest broadly similar cardiovas-

also excellent clinical trial data proving that lowering BP with

cular protection from BP-lowering with ACEIs, CCBs, and

other classes of drugs, including ACEIs, ARBs, -blockers

ARBs, as with thiazide-type diuretics and BBs, although

(BBs), and calcium channel blockers (CCBs), also reduces

some specific outcomes may differ between the classes.

the complications of hypertension.90,101,102,107,109–112 Several

There do not appear to be systematic outcome differences

randomized controlled trials have demonstrated reduction in

between dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridine CCBs in

CVD with BBs, but the benefits are less consistent than with

hypertension morbidity trials. On the basis of other data,

diuretics.107,108 The European Trial on Systolic Hypertension

short-acting CCBs are not recommended in the management

in the Elderly (Syst-EUR) study showed significant reduc-

of hypertension.

tions in stroke and all CVD with the dihydropyridine CCB,nitrendipine, compared with placebo.113 The Heart Outcomes

Rationale for Recommendation of Thiazide-Type Diuretics

Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) trial, which was not restricted

as Preferred Initial Agent

to hypertensive individuals but which included a sizable

In trials comparing diuretics with other classes of antihyper-

hypertensive subgroup, showed reductions in a variety of

tensive agents, diuretics have been virtually unsurpassed in

CVD events with the ACEI ramipril compared with placebo

preventing the cardiovascular complications of hypertension.

in individuals with prior CVD or diabetes mellitus combined

In the ALLHAT study, which involved more than 40 000

with other risk factor(s).110 The European trial on reduction of

hypertensive individuals,109 there were no differences in the

cardiac events with perindopril in stable coronary artery

primary CHD outcome or mortality between the thiazide-type

TABLE 10.

Oral Antihypertensive Drugs

Usual Dose Range,

Drug (Trade Name)

Thiazide diuretics

Chlorothiazide (Diuril)

Chlorthalidone (generic)

Hydrochlorothiazide (Microzide, HydroDIURIL†)

Polythiazide (Renese)

Indapamide (Lozol†)

Metolazone (Mykrox)

Metolazone (Zaroxolyn)

Bumetanide (Bumex†)

Furosemide (Lasix†)

Torsemide (Demadex†)

Amiloride (Midamor†)

Triamterene (Dyrenium)

Aldosterone receptor blockers

Eplerenone (Inspra)

Atenolol (Tenormin†)

Betaxolol (Kerlone†)

Bisoprolol (Zebeta†)

Metoprolol extended release (Toprol XL)

Nadolol (Corgard†)

Propranolol (Inderal†)

Propranolol long-acting (Inderal LA†)

Timolol (Blocadren†)

BBs with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity

Acebutolol (Sectral†)

Penbutolol (Levatol)

Pindolol (generic)

Combined ␣-blockers and BBs

Carvedilol (Coreg)

Labetalol (Normodyne, Trandate†)

Benazepril (Lotensin†)

Captopril (Capoten†)

Enalapril (Vasotec†)

Fosinopril (Monopril)

Lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril†)

Moexipril (Univasc)

Perindopril (Aceon)

Quinapril (Accupril)

Ramipril (Altace)

Trandolapril (Mavik)

Angiotensin II antagonists

Candesartan (Atacand)

Eprosartan (Teveten)

Irbesartan (Avapro)

Losartan (Cozaar)

Olmesartan (Benicar)

Telmisartan (Micardis)

Valsartan (Diovan)

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

TABLE 10.

Oral Antihypertensive Drugs (continued)

Usual Dose Range,

Drug (Trade Name)

Diltiazem extended release (Cardizem CD,

Dilacor XR, Tiazac†)

Diltiazem extended release (Cardizem LA)

Verapamil immediate release (Calan, Isoptin†)

Verapamil long acting (Calan SR, Isoptin SR†)

Verapamil (Coer, Covera HS, Verelan PM)

Amlodipine (Norvasc)

Felodipine (Plendil)

Isradipine (Dynacirc CR)

Nicardipine sustained release (Cardene SR)

Nifedipine long-acting (Adalat CC, Procardia

Nisoldipine (Sular)

Doxazosin (Cardura)

Prazosin (Minipress†)

Terazosin (Hytrin)

Central ␣2 agonists and othercentrally acting drugs

Clonidine (Catapres†)

Clonidine patch (Catapres-TTS)

Methyldopa (Aldomet†)

Reserpine (generic)

Guanfacine (Tenex†)

Direct vasodilators

Minoxidil (Loniten†)

Source: Physicians' Desk Reference. 57th ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson PDR; 2003.

*In some patients treated once daily, the antihypertensive effect may diminish toward the end of the dosing interval (trough effect). BP should be measured just

prior to dosing to determine if satisfactory BP control is obtained. Accordingly, an increase in dosage or frequency may need to be considered. These dosages mayvary from those listed in the Physician's Desk Reference, 57th ed.

†Available now or soon to become available in generic preparations.

diuretic chlorthalidone, the ACEI lisinopril, or the CCB

were generally the equivalent of 25 to 50 mg of hydrochlo-

amlodipine. Stroke incidence was greater with lisinopril than

rothiazide or 12.5 to 25 mg of chlorthalidone, although

chlorthalidone therapy, but these differences were present

therapy may be initiated at lower doses and titrated to these

primarily in blacks, who also had less BP lowering with

doses if tolerated. Higher doses have been shown to add

lisinopril than diuretics. The incidence of HF was greater in

little additional antihypertensive efficacy but are associ-

CCB-treated and ACEI-treated individuals compared with

ated with more hypokalemia and other adverse

those receiving the diuretic in both blacks and whites. In the

effects.119 –122

Second Australian National Blood Pressure (ANBP2) study,

Uric acid will increase in many patients receiving a

which compared the effects of an ACEI-based regimen

diuretic, but the occurrence of gout is uncommon with

against diuretics-based therapy in 6000 white hypertensive

dosages ⱕ50 mg/d of hydrochlorothiazide or ⱕ25 mg of

individuals, cardiovascular outcomes were less in the ACEI

chlorthalidone. Some reports have described an increased

group, with the favorable effect apparent only in men.112

degree of sexual dysfunction when thiazide diuretics, partic-

CVD outcome data comparing ARB with other agents are

ularly at high doses, are used. In the Treatment of Mild

Hypertension Study (TOMHS), participants randomized to

Clinical trial data indicate that diuretics are generally

chlorthalidone reported a significantly higher incidence of

well tolerated.103,109 The doses of thiazide-type diuretics

erection problems through 24 months of the study; however,

used in successful morbidity trials of low-dose diuretics

the incidence rate at 48 months was similar to placebo.123 The

TABLE 11.

Combination Drugs for Hypertension

Fixed-Dose Combination, mg*

Amlodipine-benazepril hydrochloride (2.5/10, 5/10, 5/20, 10/20)

Trandolapril-verapamil (2/180, 1/240, 2/240, 4/240)

ACEIs and diuretics

Benazepril-hydrochlorothiazide (5/6.25, 10/12.5, 20/12.5, 20/25)

Captopril-hydrochlorothiazide (25/15, 25/25, 50/15, 50/25)

Enalapril-hydrochlorothiazide (5/12.5, 10/25)

Fosinopril-hydrochlorothiazide (10/12.5, 20/12.5)

Lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide (10/12.5, 20/12.5, 20/25)

Prinzide, Zestoretic

Moexipril-hydrochlorothiazide (7.5/12.5, 15/25)

Quinapril-hydrochlorothiazide (10/12.5, 20/12.5, 20/25)

ARBs and diuretics

Eprosartan-hydrochlorothiazide (600/12.5, 600/25)

Losartan-hydrochlorothiazide (50/12.5, 100/25)

Olmesartan medoxomil-hydrochlorothiazide (20/12.5, 40/12.5, 40/25)

Valsartan-hydrochlorothiazide (80/12.5, 160/12.5, 160/25)

BBs and diuretics

Atenolol-chlorthalidone (50/25, 100/25)

Bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide (2.5/6.25, 5/6.25, 10/6.25)

Metoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide (50/25, 100/25)

Nadolol-bendroflumethiazide (40/5, 80/5)

Propranolol LA-hydrochlorothiazide (40/25, 80/25)

Centrally acting drug and diuretic

Methyldopa-hydrochlorothiazide (250/15, 250/25, 500/30, 500/50)

Reserpine-chlorthalidone (0.125/25, 0.25/50)

Reserpine-chlorothiazide (0.125/250, 0.25/500)

Diuretic and diuretic

Spironolactone-hydrochlorothiazide (25/25, 50/50)

Triamterene-hydrochlorothiazide (37.5/25, 75/50)

BB indicates -blocker; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

*Some drug combinations are available in multiple fixed doses. Each drug dose is reported in milligrams.

VA Cooperative study did not document a significant differ-

not shown an increase in serum cholesterol in diuretic-

ence in the occurrence of sexual dysfunction using diuretics

treated patients.124,125 In ALLHAT, serum cholesterol did

compared with other antihypertensive medications103 (see the

not increase from baseline in any group, but it was 1.6

section Erectile Dysfunction). Adverse metabolic effects

mg/dL lower in the CCB group and 2.2 mg/dL lower in the

may occur with diuretics. In ALLHAT, diabetes incidence

ACEI group than in diuretic-treated patients.109 Thiazide-

after 4 years of therapy was 11.8% with chlorthalidone

induced hypokalemia could contribute to increased ven-

therapy, 9.6% with amlodipine, and 8.1% with lisinopril.

tricular ectopy and possible sudden death, particularly with

However, those differences did not translate to fewer CV

high doses of thiazides in the absence of a potassium-

events for the ACEI or CCB groups.109 Those who were

sparing agent.121 In the Systolic Hypertension in the

already diabetic had fewer CV events in the diuretic group

Elderly Program (SHEP) trial, the positive benefits of

than with ACEI treatment. Trials longer than 1 year

diuretic therapy were not apparent when serum potassium

duration using modest doses of diuretics generally have

levels were below 3.5 mmol/L.126 However, other studies

Chobanian et al

JNC 7 – COMPLETE REPORT

have become available in generic form, their cost has beenreduced. Despite the various benefits of diuretics, they remainunderutilized.128

Achieving Blood Pressure Control in

Individual Patients

The algorithm for the treatment of hypertensive patients is

shown in Figure 16. Therapy begins with lifestyle modifica-

tion, and if the BP goal is not achieved, thiazide-type

diuretics should be used as initial therapy for most patients,

either alone or in combination with one of the other classes

(ACEIs, ARBs, BBs, CCBs) that have also been shown to

reduce one or more hypertensive complications in random-

ized controlled outcome trials. Selection of one of these other

agents as initial therapy is recommended when a diuretic

cannot be used or when a compelling indication is present

that requires the use of a specific drug, as listed in Table 12.

If the initial drug selected is not tolerated or is contraindi-

cated, then a drug from one of the other classes proven to

reduce cardiovascular events should be substituted.

Since most hypertensive patients will require 2 or more

antihypertensive medications to achieve their BP goals,addition of a second drug from a different class should beinitiated when use of a single agent in adequate doses fails toachieve the goal. When BP is more than 20 mm Hg abovesystolic goal or 10 mm Hg above diastolic goal, considerationshould be given to initiate therapy with 2 drugs, either as

Figure 16. Algorithm for treatment of hypertension.

separate prescriptions or in fixed-dose combinations (Figure16).129

have not demonstrated increased ventricular ectopy as a

The initiation of therapy with more than one drug increases

result of diuretic therapy.127 Despite potential adverse

the likelihood of achieving BP goal in a more timely fashion.

metabolic effects of diuretics, with laboratory monitoring,

The use of multidrug combinations often produces greater BP

thiazide-type diuretics are effective and relatively safe for

reduction at lower doses of the component agents, resulting in

the management of hypertension.

fewer side effects.129,130

Thiazide diuretics are less expensive than other antihyper-

The use of fixed-dose combinations may be more conve-

tensive drugs, although as members of other classes of drugs

nient and simplify the treatment regimen and may cost less

TABLE 12.

Clinical Trial and Guideline Basis for Compelling Indications for Individual Drug Classes

Recommended Drugs

Compelling Indication*

Clinical Trial Basis†

ACC/AHA Heart Failure Guideline,132MERIT-HF,133 COPERNICUS,134 CIBIS,135SOLVD,136 AIRE,137 TRACE,138 ValHEFT,139RALES,140 CHARM141

ACC/AHA Post-MI Guideline,142 BHAT,143SAVE,144 Capricorn,145 EPHESUS146

High coronary disease risk

ALLHAT,109 HOPE,110 ANBP2,112 LIFE,102CONVINCE,101 EUROPA,114 INVEST147

NKF-ADA Guideline,88,89 UKPDS,148ALLHAT109

Chronic kidney disease

NKF Guideline,89 Captopril Trial,149RENAAL,150 IDNT,151 REIN,152 AASK153

Recurrent stroke prevention

BB indicates -blocker; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; Aldo ANT, aldosterone

*Compelling indications for antihypertensive drugs are based on benefits from outcome studies or existing clinical guidelines; the compelling indication is managed

in parallel with the BP.

†Conditions for which clinical trials demonstrate benefit of specific classes of antihypertensive drugs used as part of an antihypertensive regimen to achieve BP

goal to test outcomes.

than the individual components prescribed separately. Use of

Ischemic Heart Disease

generic drugs should be considered to reduce prescription

Hypertensive patients are at increased risk for myocardial

costs, and the cost of separate prescription of multiple drugs

infarction (MI) or other major coronary event and may be at

available generically may be less than nongeneric, fixed-dose

higher risk of death following an acute MI. Myocardial

combinations. The starting dose of most fixed-dose combi-

oxygen supply in hypertensives may be limited by coronary

nations is usually below the doses used in clinical outcome

artery disease (CAD) while myocardial oxygen demand is

trials, and the doses of these agents should be titrated upward

often greater because of the increased impedance to left

to achieve the BP goal before adding other drugs. However,

ventricular ejection and the frequent presence of left ventric-

caution is advised in initiating therapy with multiple agents,

ular hypertrophy (LVH).154 Lowering both SBP and DBP

particularly in some older persons and in those at risk for

reduces ischemia and prevents CVD events in patients with

orthostatic hypotension, such as diabetics with autonomic

CAD, in part by reducing myocardial oxygen demand. One

caveat with respect to antihypertensive treatment in patientswith CAD is the finding in some studies of an apparent

Follow-Up and Monitoring

increase in coronary risk at low levels of DBP. For example,

Once antihypertensive drug therapy is initiated, most patients

in the SHEP study, lowering DBP to ⬍55 or 60 mm Hg was

should return for follow-up and adjustment of medications at

associated with an increase in cardiovascular events, includ-

monthly intervals or less until the BP goal is reached. More

ing MI.155 No similar increase in coronary events (a J-shaped

frequent visits will be necessary for patients with stage 2

curve) has been observed with SBP. Patients with occlusive

hypertension or with complicating comorbid conditions. Se-

CAD and/or LVH are put at risk of coronary events if DBP is

rum potassium and creatinine should be monitored at least 1

low. Overall, however, many more events are prevented than

to 2 times/year. After BP is at goal and stable, follow-up visits

caused if BP is aggressively treated.

can usually be at 3- to 6-month intervals. Comorbidities such

Stable Angina and Silent Ischemia

as HF, associated diseases such as diabetes, and the need for

Therapy is directed toward preventing MI and death and

laboratory tests influence the frequency of visits. Other

reducing symptoms of angina and the occurrence of ischemia.

cardiovascular risk factors should be monitored and treated to

Unless contraindicated, pharmacological therapy should be

their respective goals, and tobacco avoidance must be pro-

initiated with a BB.142,156 BBs will lower BP, reduce symp-

moted vigorously. Low-dose aspirin therapy should be con-

toms of angina, improve mortality, and reduce cardiac output,

sidered only when BP is controlled because of the increased

heart rate, and AV conduction. The reduced inotropy and

risk of hemorrhagic stroke when the hypertension is not

heart rate decrease myocardial oxygen demand. Treatment

should also include smoking cessation, management of dia-betes, lipid lowering, antiplatelet agents, exercise training,

Special Situations in

and weight reduction in obese patients.

If angina and BP are not controlled by BB therapy alone, or

if BBs are contraindicated, as in the presence of severe

Hypertension may exist in association with other conditions

reactive airway disease, severe peripheral arterial disease,

in which there are compelling indications for use of a

high-degree AV block, or the sick sinus syndrome, either

particular treatment based on clinical trial data demonstrating

long-acting, dihydropyridine or nondihydropyridine-type

benefits of such therapy on the natural history of the associ-

CCBs may be used. CCBs decrease total peripheral resis-

ated condition (Table 12). Compelling indications for specific

tance, which leads to reduction in BP and in wall tension.

therapy involve high-risk conditions that can be direct se-

CCBs also decrease coronary resistance and enhance postste-

quelae of hypertension (HF, ischemic heart disease, chronic

notic coronary perfusion. Nondihydropyridine CCBs also can

kidney disease, recurrent stroke) or commonly associated

decrease heart rate, but when in combination with a BB, they

with hypertension (diabetes, high coronary disease risk).

may cause severe bradycardia or high degrees of heart block.

Therapeutic decisions in such individuals should be directed

Therefore, long-acting dihydropyridine CCBs are preferred

at both the compelling indication and BP lowering.

for combination therapy with BBs. If angina or BP is still notcontrolled on this two-drug regimen, nitrates can be added,

The absence of a positive indication can signify a lack of

but these should be used with caution in patients taking

information for a particular drug class. For example, in

phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors such as sildenafil. Short-