Integration of chemical and rnai multiparametric profiles identifies triggers of intracellular mycobacterial killing

Cell Host & MicrobeArticle

Integration of Chemical and RNAiMultiparametric Profiles IdentifiesTriggers of Intracellular Mycobacterial Killing

Varadharajan Rico Nikolay Giovanni Jerome Gilleron,Inna Kalaidzidis,Felix Meyenhofer,Marc Yannis Kalaidzidis,and Marino 1Max-Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, 108 Pfotenhauerstrasse, 01307 Dresden, Germany2Belozersky Institute of Physico-Chemical Biology, Moscow State University, 119899 Moscow, Russia*Correspondence:

Exploiting host processes to fight against infectious diseases

is currently an underexplored approach. Yet, it presents

Pharmacological modulators of host-microbial inter-

several advantages. First, the host processes exploited by

actions can in principle be identified using high-

pathogens are well studied from both a mechanistic and

content screens. However, a severe limitation of

a physiological perspective ). Second, host

this approach is the lack of insights into the mode

kinase and phosphatase inhibitors that kill intracellular myco-

of action of compounds selected during the primary

bacteria have been successfully identified, thus validating the

screen. To overcome this problem, we developed a

approach (;Third, it could better prevent the emergence

combined experimental and computational ap-

of drug-resistant strains (

proach. We designed a quantitative multiparametric

). Additionally, critical host cellular responses are con-

image-based assay to measure intracellular myco-

served across diverse mycobacterial strains, including drug-

bacteria in primary human macrophages, screened

resistant ones (Given the complexity of

a chemical library containing FDA-approved drugs,

mycobacteria-host interactions, we reasoned that the target

and validated three compounds for intracellular

space for perturbations acting upon the host could be signifi-

killing of M. tuberculosis. By integrating the multi-

cantly larger than so far explored.

parametric profiles of the chemicals with those of

Since mycobacteria block phagosome maturation

siRNAs from a genome-wide survey on endocytosis,

; a substantial target

we predicted and experimentally verified that two

space could be related to endosomal/phagosomal trafficking.

compounds modulate autophagy, whereas the third

This could be explored by cell-based small molecule screensmonitoring intracellular mycobacterial survival. However, a

accelerates endosomal progression. Our findings

severe constraint is that the primary assay typically does not

demonstrate the value of integrating small molecules

have the resolution to provide insights into the mode of function

and genetic screens for identifying cellular mecha-

of the selected hits ().

nisms modulated by chemicals. Furthermore, selec-

In this study, we addressed this challenge by exploiting our

tive pharmacological modulation of host trafficking

knowledge of the molecular regulation of the endocytic path-

pathways can be applied to intracellular pathogens

way. We recently performed a cell-based genome-wide RNAi

screen on endocytosis capturing various features of the endo-cytic system by quantitative multiparametric image analysis(QMPIA) (The QMPIA uncovered general

principles governing endocytic trafficking that can also beapplied to the analysis of phagosome maturation. Here, we

Tuberculosis is a disease characterized by an extensive array of

first established a high-content assay to quantify intracellular

interactions between mycobacteria and the host. To maintain

mycobacterial survival and screened a library of pharmacologi-

their intracellular niche, mycobacteria influence a variety of

cally active compounds to identify host-specific modulators.

fundamental host cell processes including apoptosis (

Second, we developed an integrated experimental and com-

putational pipeline to compare the multiparametric profiles

(), trafficking (

from the chemical screen with those from the genome-wide

; ), and signaling ().

siRNA screen (This approach identified

Therefore, a pharmacological modulation of the host cell mech-

chemicals capable of overpowering intracellular mycobacterial

anisms that are hijacked by the bacteria could, on the one hand,

survival by modulating the cellular trafficking processes. Our

be used to explore the processes altered during the infection

results highlight the value of multiparametric phenotypic anal-

and, on the other hand, lead to development of anti-TB

ysis to extract functional information from combined chemical

and genomic screens.

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 129

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

Validation of Three Compounds on M. tuberculosisTo validate the results from the screen, we selected three com-

High-Content Chemical Screen to Identify Modulators of

pounds within the cluster M5, namely Nortriptyline, Prochlorper-

azine edisylate (PE), and Haloperidol on

We developed an integrated experimental and computational

the basis of (1) amplitude of the phenotypes (

strategy for screening, selecting and validating compounds en-

showing reduced bacterial intensity, fewer bacteria,

dowed with antimycobacterial activity by acting on the host

and infected cells; and (2) lack of effect in the alamar blue screen.

machinery (A). We first established a high-content

Additionally, these compounds did not show bacteriostatic

assay in a human primary macrophage infection model

activity on M. bovis BCG-GFP at neutral and acidic pH

see the online).

B and S2C), or plate assay of M. tuberculosis (data not

Briefly, cells were infected with M. bovis BCG expressing

GFP and were incubated with

To determine whether the phenotype observed on M. bovis

chemicals for 48 hr. Since our primary interest was to identify

BCG-GFP was reproducible on pathogenic M. tuberculosis, we

chemical modulators disrupting the host-mycobacteria equilib-

performed a colony-forming unit (CFU) assay on M. tuberculosis

rium, chemicals were added after the infection. Cells were

strain H37Rv and two clinical strains using the three selected

then fixed and nuclei and cytoplasm stained and imaged using

an automated spinning disc confocal microscope. We devel-

Rapamycin ), and H89

oped further the QMPIA platform previously used to auto-

as controls. All three selected compounds caused a significant

matically identify cells, endosomes, and nuclei

reduction in bacterial colonies in all the strains F), con-

) by implementing automated algo-

firming that they impair intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis.

rithms to detect various features of intracellular bacteria andhost cell simultaneously ().

Integration of Multiparametric Chemical and Genetic

We screened a bioactive library (Microsource Discovery

Data Sets to Identify Cellular Processes Modulated by

Inc., Spectrum collection, 2,000 compounds) comprising

most FDA-approved drugs. The compounds produced repro-

Since we aimed to identify compounds restoring mycobacteria-

ducible alterations of various parameters such as bacterial

arrested phagosome maturation, we explored the effects of the

number, intensity, and bacterial and host cell morphology

selected compounds on mycobacterial trafficking. We quantified

the colocalization of M. bovis BCG-GFP with lysobisphosphati-

We performed cluster analysis using an improvement of the

dic acid (LBPA), a marker of late endocytic compartments (

method previously used ) based on density

estimation (N.S., T. Galvez, C. Collinet, G.M., M.Z., and Y.K.,

and D and S2E). Infected cells treated with the

unpublished data; The compounds

selected compounds showed significantly higher colocalization

grouped into six distinct clusters, each with a distinct pattern,

than control cells G), indicating that the arrest in phag-

i.e., phenotypic profile (and 1D, Table S1). The

osome maturation was reverted.

strength of the phenotype is given by its phenoscore. Due to

A significant challenge in phenotypic chemical screens is to

the multiparametric nature of our screening output, we expected

gain insights into the mechanism of action of the selected

each cluster to capture distinct phenotypic features of mycobac-

compounds. Multiparametric profiles are specific signatures of

teria and the host. Cluster M5 (containing 115 compounds) was

either chemical or genetic perturbations because they capture

of particular interest, as it was characterized by a strong reduc-

multiple facets of a biological system. Since random matches

tion of bacterial parameters but relatively weak changes in host

between such profiles are unlikely, clues into the molecular

parameters reflecting toxicity, suggesting that the compounds in

processes targeted by the chemicals could be obtained in

this cluster are detrimental to bacteria but not significantly toxic

principle by systematically searching for genetic alterations pro-

to the host.

ducing similar phenotypes. Hence, we aimed to match the multi-

Since we aimed to identify compounds that act upon the host,

parametric profiles of the compounds from the mycobacteria

we counterselected those directly killing mycobacteria by

screen with those of the siRNAs from the genome-wide endocy-

screening the MSD library using the alamar blue assay (see

tosis screen (However, the two screens are

the Interestingly, only six com-

not directly comparable due to their distinct characteristics, i.e.,

pounds were shared with cluster M5, suggesting that most

a chemical screen on intracellular mycobacterial survival in

compounds in this cluster are not bacteriostatic. Additionally,

human primary macrophages versus a functional genomics

compounds functionally annotated as ‘‘antibacterial'' were not

screen on endocytosis in HeLa cells. To overcome this problem,

enriched in cluster M5 despite scoring in the alamar blue screen

we bridged the two data sets via an intermediate screen, where

(B). Standard antimycobacterial drugs were not en-

the compounds from cluster M5 were screened on the endocy-

riched in any particular cluster and yielded weak phenotypes

tosis assay in HeLa cells (A). HeLa cells were pretreated

(C–S1F, ). This is probably

with the compounds prior to the internalization of fluorescently

because our cell-based assay measures the reduction in GFP

labeled epidermal growth factor (EGF) and Transferrin (Tfn) for

fluorescence and therefore primarily reflects modulation of lyso-

10 min (), imaged, and multiple parameters

somal degradation. Thus, the compounds of cluster M5 could

extracted ().

modulate cellular processes at the host-pathogen interface

Density estimation-based clustering separated the com-

rather than acting directly on the bacteria.

pounds into two subclusters, E1 and E2 (Table S2),

130 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

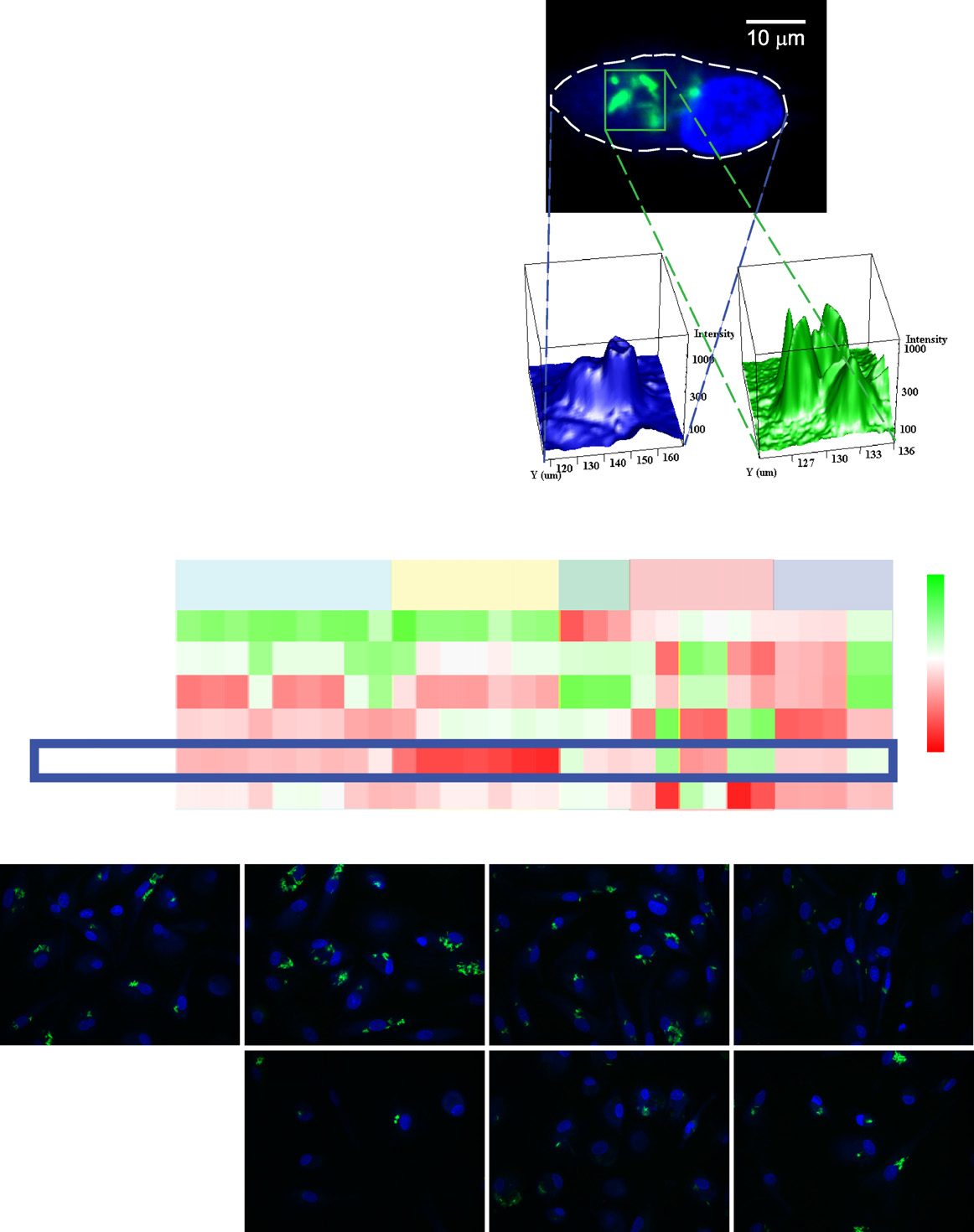

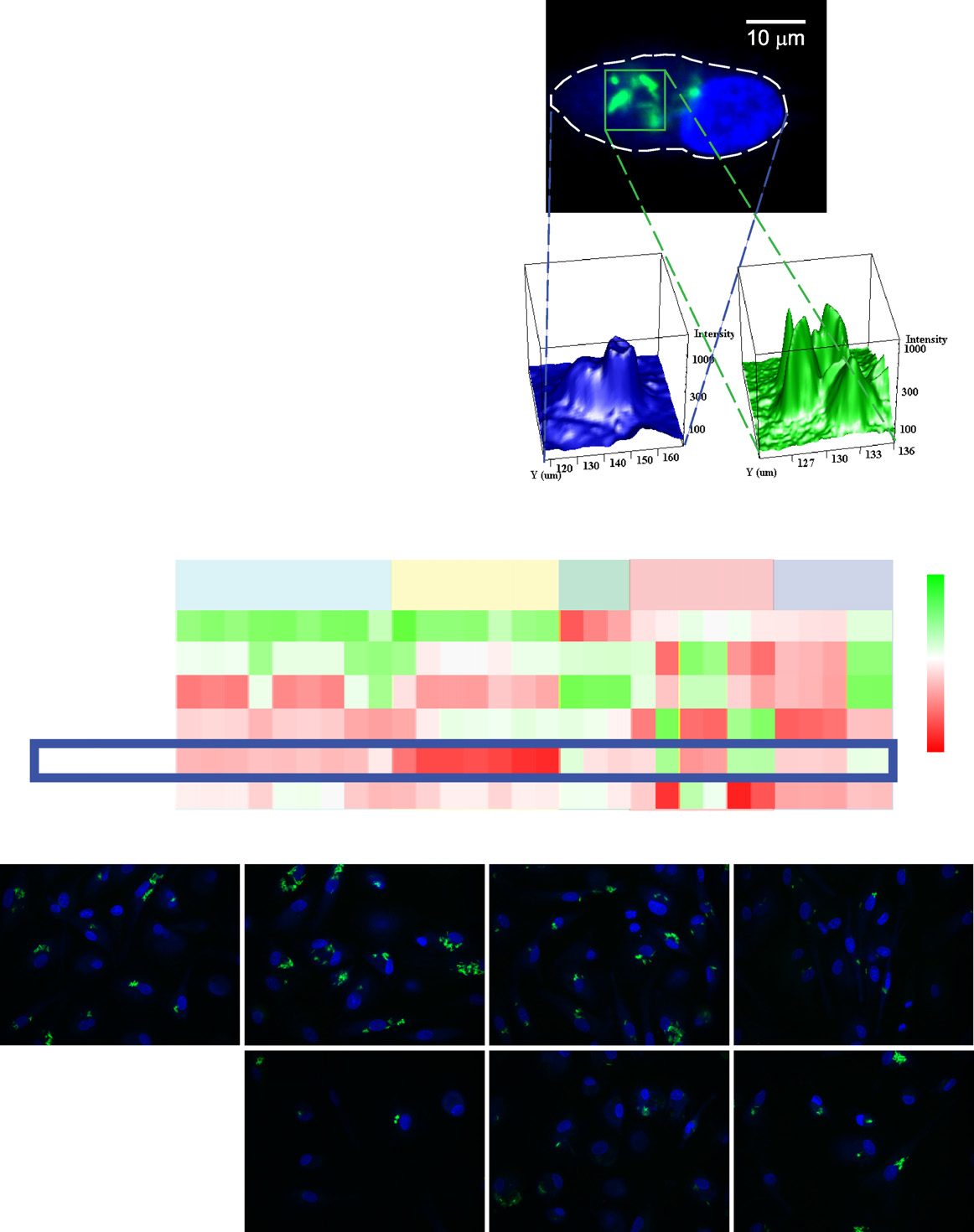

Figure 1. High-Content Image-Based Screen for Intracellular Mycobacteria Survival(A) Flowchart of the experimental and computational pipeline used in this study.

(B) (Ba) Representative example of a human primary monocyte-derived macrophage infected with M. bovis BCG-GFP with cell contours (dashed line). (Bb)Segmentation of macrophage: intensity distribution of nuclear and cytoplasmic regions used to draw the contours of the cell. (Bc) Segmentation of bacteria:intensity distribution of bacteria in the region marked in the green square used for fitting the bacteria model.

(C) Heatmap representation of the mycobacteria high-content chemical screen after density estimation-based clustering. Rows denote cluster IDs and number ofcompounds. Columns are parameters of the high-content assay (). M5 is the cluster analyzed in this study.

(D) Representative images from clusters M1–M6.

See also and Table S1.

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 131

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

DAPI/Cell Mask Blue

M. bovis BCG-GFP

M. bovis BCG-GFP with LBPA

Colocalisation coef 0.1

Colocalisation threshold

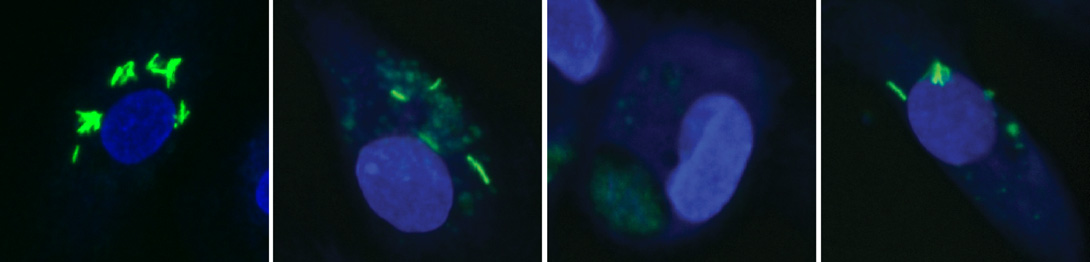

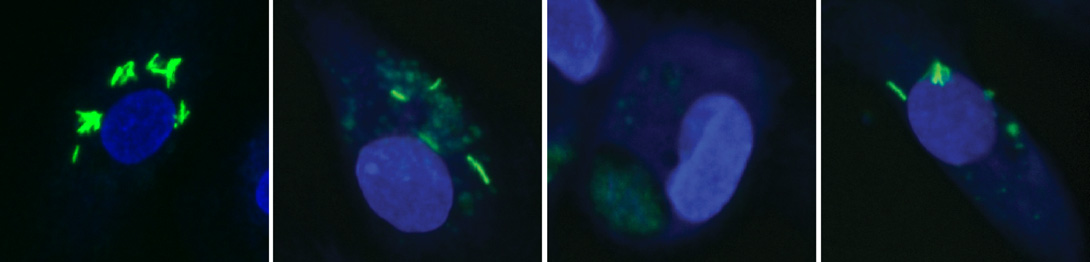

Figure 2. Validation of Three Selected Compounds for Intracellular Mycobacterial Survival(A–D) Representative images of infected cells treated with DMSO (A), Nortriptyline (B), prochlorperazine edisylate (PE) (C), and Haloperidol (D) at a concentrationof 10 mM for 48 hr after infection. Arrowheads indicate GFP-positive structures that are identified as ‘‘bacteria'' by the QMPIA. Scale bar, 10 mm.

(E) Quantitative multiparametric profiles of the phenotypes in (A)–(D) with the Z score (y axis) of the parameters (1–30) showing, e.g., decrease in number andintensity of intracellular mycobacteria. Error bars represent SEM.

(F) CFU analysis of human primary monocyte-derived macrophages infected with virulent M. tuberculosis H37Rv or two different clinical isolates CS1 and CS2and treated with the indicated compounds for 48 hr (pooled data from two independent biological replicates with at least three technical replicates each). Errorbars represent SD. D (DMSO 0.01%), Rf (Rifampin 2 mM), Rp (Rapamycin, 5.5 mM), PE (Prochlorperazine edisylate, 10 mM), N (Nortriptyline, 10 mM), H (Haloperidol,10 mM), H89 (H89, 10 mM). p values for all compounds tested (except H89) were <0.0001 and <0.01, for H37Rv and the two clinical strains, respectively.

(G) Colocalization of M. bovis BCG-GFP and LBPA in cells treated with the indicated drugs. Number of cells analyzed per condition is indicated. Error bars areSEM. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Abbreviations and concentrations are as in (F). See also

132 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

Figure 3. Integration of Chemical and RNAi Screen Data Sets(A) Scheme illustrating the integration of the primary chemical (green) and RNAi (blue) screen datasets via an intermediate screen on the chemicals fromcluster M5.

(B and C) Endocytosis (B) and autophagy(C) profiles of subclusters E1 and E2 from cluster M5. The profiles are average representations of Z scores of theindividual compounds within each subcluster. Parameters are grouped into different phenotype classes.

(D and E) Dose-response curves of mean integral intensities of M. bovis BCG-GFP (blue) and LC3 (magenta) for Nortryptyline (D) and prochlorperazine edisylate(E). Error bars are SEM, number of images is 25, data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(F) Summary of IC50 values calculated from curves in (D) and (E). See also , Table S2, and Table S3.

suggesting that the compounds may act by at least two distinct

sets of genes that are most likely to show similar phenotypes

mechanisms. To identify them, we compared the multiparamet-

(). We computed their representation

ric profiles of the subclusters E1 and E2 to the genome-wide

in KEGG pathways and GO terms (Table S3) and found that

RNAi screen data set (and identified the

‘‘mTOR regulation'' and ‘‘regulation of autophagy and mTOR''

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 133

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

were significantly enriched in the E1 (p = 1.2 3 10�4 and

tion (autophagic flux) (). To distinguish

9 3 10�4, respectively) but not the E2 (p = 0.15 and 0.4, respec-

between these possibilities, we used two approaches. First,

tively) subcluster.

we tested whether blockers of lysosomal degradation, e.g.,inhibitors of acidification (BafilomycinA1 or Chloroquine) that

High-Content Autophagy Chemical Screen

inhibit autophagic flux, had an additive effect with the com-

Autophagy is a key process regulated by mTOR (

pounds on autophagosome accumulation (

and a known mediator of intracellular mycobac-

). HeLa cells were treated with Nortriptyline and PE in the

terial survival ; The inte-

presence or absence of BafilomycinA1, and LC3 lipidation

gration approach predicted that compounds from E1 modulate

(LC3-II band) was assessed by immunoblotting. Whereas both

autophagy. To test it, we treated HeLa cells with the compounds,

Nortriptyline and PE showed significant increase in the LC3-II

immunostained for the autophagosome marker LC3, and

band, additive effects of BafilomycinA1 were seen only upon

extracted multiple parameters reporting diverse facets of auto-

Nortriptyline, but not PE, treatment In addition,

phagosomes ). The compounds of

we generated HeLa cells stably expressing LC3 fused to GFP

subcluster E1, but not E2, had a strong effect on autophagy

under the control of the endogenous promoter through BAC re-

(A), thus validating the prediction from the

combineering (HeLa BAC LC3-GFP; The

integration analysis. Of the three compounds validated in intra-

results B and S5C) confirmed that Nortriptyline, but

cellular mycobacterial killing, Nortriptyline and PE belong to

not PE, had an additive effect with BafilomycinA1 and Chloro-

subcluster E1, whereas Haloperidol belongs to E2. Consistent

quine in increasing LC3-GFP vesicles.

with the data of Nortriptyline and PE, similar to Rapa-

Second, we used an established assay for measuring auto-

mycin or serum starvation (by HBSS), showed a strong effect on

phagic flux based on a tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3 construct

autophagy, whereas Haloperidol did not (and S3C).

(). Since GFP is quenched in the acidic envi-

Human primary macrophages treated with Nortriptyline and PE

ronment of autophagolysosomes whereas mRFP remains

resembled HeLa cells in showing an increase in both number

stable, a block in autophagy flux results in higher colocalization

and integral intensity of LC3 vesicles (D and S3E),

of mRFP and GFP compared to induction of autophagy. HeLa

indicating that their effect of increasing autophagosomes is not

cells stably expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 (

) were treated with the compounds, and the colocalization

To determine whether the accumulation of autophagosomes

between mRFP and GFP was quantified. Nortriptyline, similar

is related to intracellular mycobacterial killing by Nortriptyline

to starvation-induced autophagy (HBSS), showed a low mRFP

and PE, we first computed their IC50 values in the two assays.

to GFP colocalization, whereas PE, similar to BafilomycinA1

For both compounds, the IC50 values for increased LC3 integral

and Chloroquine, yielded higher colocalization A and

intensity correlated well with decreased M. bovis BCG-GFP

5B). Similar results were obtained for the colocalization of LC3-

(D–3F), arguing that the two phenotypes are linked.

GFP with LBPA in HeLa-LC3-GFP cells Based on

Second, if autophagy modulation were involved in intracellular

previous studies these results can be in-

mycobacterial killing, we should visualize mycobacteria within

terpreted as indicating that Nortriptyline induces autophagy

autophagosomes. To test this, we analyzed mycobacteria-

whereas PE inhibits autophagic flux.

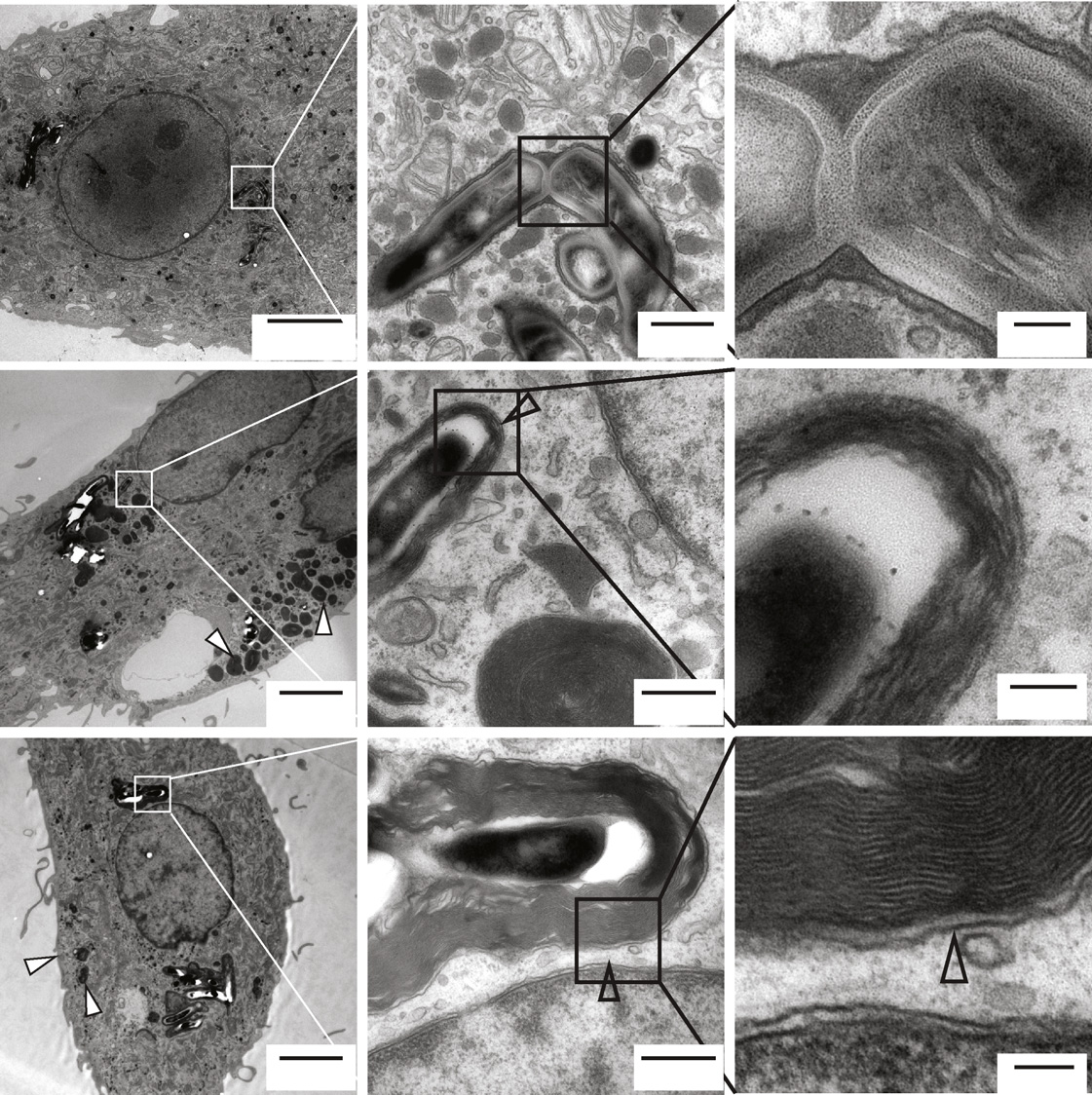

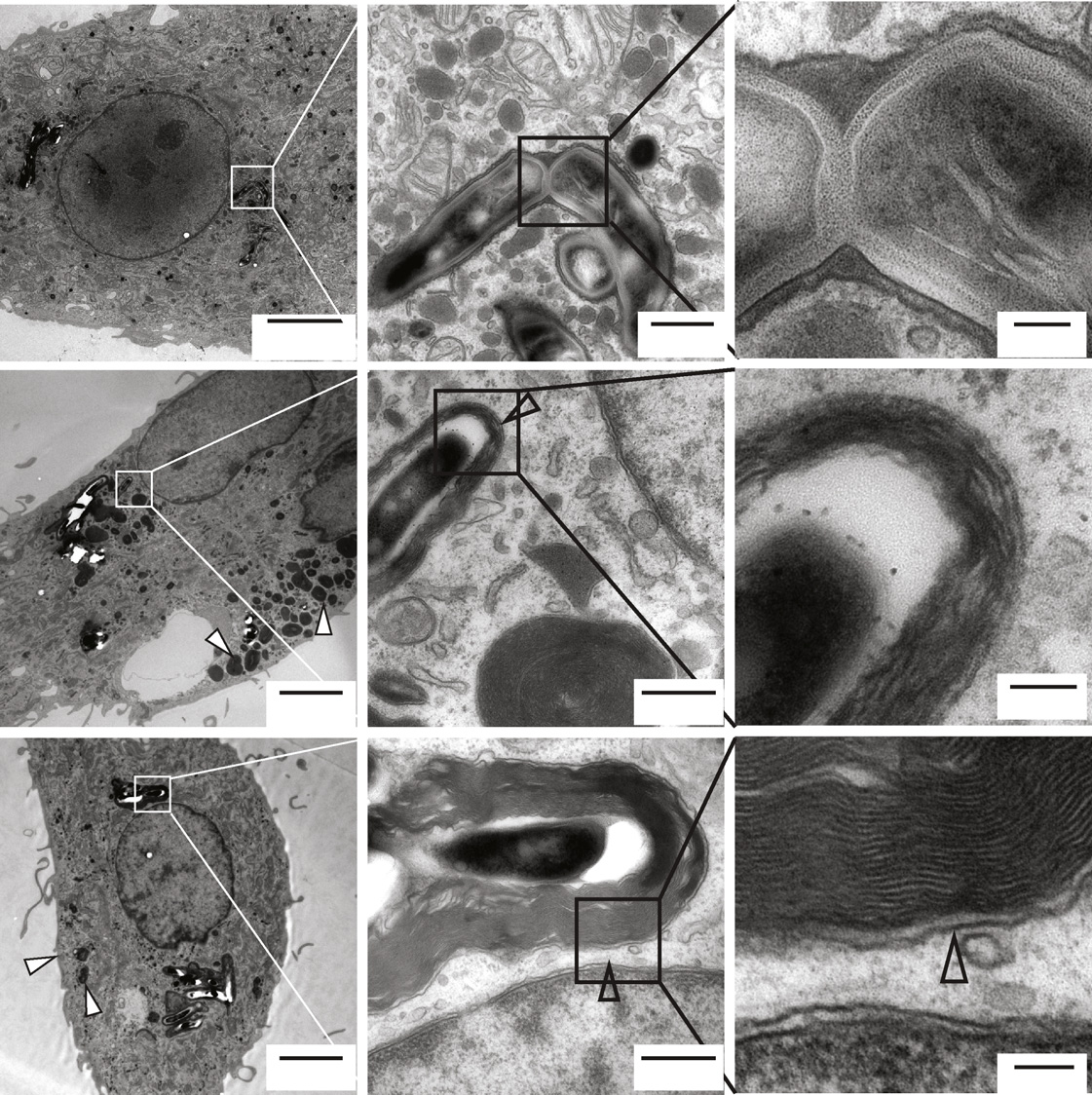

infected cells by electron microscopy. Whereas in control cells

In principle, blockers of autophagy flux should not have a detri-

mycobacteria resided within single-membrane phagosomes

mental effect on mycobacteria. Indeed, inhibitors of autophagy

(cells treated with Nortriptyline and PE clearly

flux that abrogate the function of lysosomes by blocking acidifi-

showed the presence of mycobacteria within autophagosomes,

cation did not affect the intensity of intracellular M. bovis

defined as vesicles containing multiple membrane whorls

BCG-GFP (E). In order to determine whether PE has

and delimited by double membrane Haloper-

a similar effect on lysosomal pH, we quantified the intensity of

idol-treated cells, as expected, did not show this effect

the acidotropic dye Lysotracker red over time. Unlike classical

(A). Finally, we tested the effect of an inhibitor of auto-

blockers of autophagy flux, PE did not have a negative effect

phagy, 3-methyladenine (3MA) ). Upon

on the acidity of lysosomes, but quite the contrary, it significantly

treatment with Nortriptyline and PE in the presence of 3-MA,

increased it (Moreover, this effect correlated with the

mycobacteria were observed not in autophagosomes but in

presence of mycobacteria within the lysotracker red-positive

phagosomes (Additionally, 3-MA reverted

vesicles C) and a concomitant reduction in bacterial

the effect of Nortriptyline on mycobacterial survival in both

intensity D).

CFU and image-based assays (data not shown), arguing that

The increased acidification by PE is in apparent contradiction

the effect of the compounds on mycobacteria is related to

with the inhibition of autophagic flux. To solve this discrepancy,

we treated HeLa cells stably expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 withthe compounds for different periods of time. If autophagy flux

Nortriptyline and PE Modulate Autophagy by Different

were completely blocked, the colocalization between mRFP

and GFP (corresponding to nonacidic autophagosomes) should

Autophagy is a multistep process consisting of autophagosome

increase with time, whereas if the flux were slowed down, then

formation, maturation, and eventual degradation by fusion with

the colocalization would be expected to decrease (i.e., autopha-

lysosomes (autophagolysosomes). The increase in autophago-

gosomes become acidic). The colocalization of mRFP and GFP

somes mediated by Nortriptyline and PE could be due to either

increased over time in cells treated with BafilomycinA1 (

a higher rate of formation or a block in maturation and degrada-

E) or Chloroquine (data not shown). In contrast, in

134 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

<0.0001 <0.0001

Autophagosome area

Figure 4. Ultrastructural Analysis of Autophagy and Intracellular Mycobacterial Survival(A–C) Electron micrographs of M. bovis BCG-GFP-infected human primary monocyte-derived macrophages treated with DMSO (A), 10 mM N (B), or PE (C) for 4 hr.

Black arrows indicate mycobacterial phagosomes, and black and white arrowheads indicate autophagosomes with and without mycobacteria, respectively.

Mitochondria (Mi), nucleus (Nuc), mycobacterial phagosome (MP), autophagosomes (AP), mycobacteria containing autophagosome (MAP).

(D–F) Quantification of number of autophagosomes (D) (n = 30), autophagosome area as percentage of total cell area (E) and total cell area (F) (n = 6) from theelectron micrographs. D (DMSO, 0.01%), N (Nortriptyline, 10 mM), PE (Prochlorperazine edisylate, 10 mM). Numbers denote p values in comparison to DMSO. Seealso

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 135

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

Figure 5. Nortriptyline and PE Modulate Autophagy Differently(A) Representative images of HeLa cells stably expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 treated with the indicated chemicals for 2 hr. DAPI/CMB denotes the cell nucleus andcytoplasm. Scale bar, 10 mm.

(B) Quantification of colocalization between the mRFP and GFP signals. The number of cells analyzed per condition is indicated. Results are representative of fourexperiments. Error bars are SEM. Abbreviations and concentrations are as in (A).

(C and D) Quantification of integral intensity of lysotracker red-labeled vesicles (C) and M. bovis BCG-GFP (D) in infected human primary macrophages treatedwith either DMSO or PE (10 mM) for the indicated periods of time. Total and bacterial LTR refer to integral intensity of all acidic compartments and those containingbacteria, respectively. Data are averaged from 45 images/condition/time point and normalized to DMSO to represent fold change (representative of twoindependent experiments).

(E) Colocalization between the mRFP and GFP signals in HeLa cells stably expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 treated with the indicated drugs for different periodsof time. Colocalization at a single threshold of 0.35 was used to generate the time response curves. Data are from 50 images per condition and from fourexperiments. For (A), (B), and (E), D (DMSO, 0.01%), Hb (HBSS), N (Nortriptyline,10 mM), ChQ (Chloroquine, 25 mM), Baf (BafilomycinA1, 100 nM), PE(10 mM).

(F) Mean integral intensity of M. bovis BCG-GFP upon treatment of infected human primary macrophages with different concentrations of IFN-g for 4 hr prior totreatment with either 1 mM or 10 mM N or PE, for 48 hr. Significance was calculated by Student's t test. NS p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001. Data areaveraged from 16 images/condition and are representative of four experiments. For (B)–(F), error bars indicate SEM. See also

PE-treated cells the colocalization increased within the first hour

induction. PE instead exerted a much weaker effect, providing

but then progressively decreased (E), showing that the

additional evidence that the two compounds interact differently

autophagosomes acidify over time.

with the autophagy machinery.

To further characterize the effects of Nortriptyline and PE on

autophagy, we tested whether they could synergize with an es-

Haloperidol Accelerates Endolysosomal Trafficking

tablished physiological inducer of autophagy, Interferon-gamma

Haloperidol kills intracellular mycobacteria by a mechanism

distinct from autophagy. Haloperidol belongs to subcluster E2

preactivated infected cells with IFN-g and assessed the effect

(This subcluster is characterized by a strong alter-

of the compound addition on mycobacterial survival. The results

ation of the endocytic profile exemplified by an increase in

were striking (F) and showed that Nortriptyline

EGF and Tfn content, increased colocalization of EGF to Tfn

synergized strongly with IFN-g, supporting its role in autophagy

(reduced sorting), and accumulation of EGF in large endosomes

136 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

Figure 6. Analysis of Endocytosis Traf-ficking by Haloperidol(A and B) The kinetics of endocytic trafficking werequantified using a cell-based LDL traffickingassay. (A) Integral intensity of LDL in early endo-somes and (B) late endosomes. Values are Htreatment (10 mM) subtracted from DMSO andderived from an average of 1,200 cells/time point.

Error bars are SEM of number of images (averageof 40 per condition). Data are representative of twoexperiments.

(C and D) A431 cells stably expressing Rab5-GFPwere treated with either DMSO or Haloperidol(10 mM) for 2 hr and imaged live. Velocities ofminus-end (toward cell center) (C) and plus-end-

directed movement (away from cell center) areshown for DMSO-treated cells (black line) andH-treated cells (green line). For curves in (B)–(D),the p value is for points denoted by asterisks (seethe ). For (C) and (D),error bars are standard deviations, n = 37 (DMSO),n = 29 (H).

(E) Mean square displacement curves for themovies (and 6D) were computed asdescribed in the . Thesecond part of the biphasic curve indicating longtimescale movements was fitted using linear least-square fit. Diffusion coefficient is derived from theslope of the fitted curves. See also Movie S1, and Movie S2.

results confirm the prediction that Halo-peridol leads to acceleration of traffickingalong the degradative pathway.

Phagosome maturation depends on

the fusion with early, late endosomesand lysosomes (;) and is regu-lated by the motility of endocytic organ-elles along the cytoskeleton and therecruitment of the membrane tetheringfusion machinery. Both processes couldbe enhanced by Haloperidol. We first

in the cell center. In accordance with the design principles of the

tested the influence of Haloperidol on endosome motility.

endocytic system (; ), the

Increasing concentration of Rab5 and displacement of early en-

alterations observed argue for a faster degradation. Hence, we

dosomes toward cell center are predictive of progression from

hypothesized that Haloperidol could positively modulate endo-

early to late endosomes (

cytic trafficking along the degradative route. To test this hypoth-

). We therefore quantified endosome motility in cells

esis, we monitored the kinetics of transport of low-density

stably expressing GFP-Rab5, as previously described (

lipoprotein (LDL) from early to late endosomes, using Rab5

) (Movie S1 and Movie S2), and computed the velocity

(and LBPA ) as markers,

toward the cell center (minus end microtubule directed) and

respectively (A). HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-

periphery (plus end) as a function of GFP-Rab5 intensity. Halo-

Rab5 from the endogenous promoter (HeLa BAC GFP-Rab5c)

peridol-treated cells showed a much higher motility of early en-

() were treated with Haloperidol and allowed

dosomes harboring high levels of Rab5, and this enhancement

to internalize LDL for different times prior to immunostaining

was higher toward the cell center (and 6D). Next,

with anti-Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) (to detect LDL) and LBPA anti-

we computed the mean square displacement of endosomes

bodies. Haloperidol significantly increased the intensity of LDL in

over time, an established way to characterize motility patterns

late, but not early, endosomes (and 6B). Similarly,

(). In Haloperidol-treated cells, long, but not

LDL-containing late, but not early, endosomes were larger,

short, timescale movements of GFP-Rab5 endosomes were

more numerous, and closer to the cell center in Haloperidol-

significantly accelerated E). Thus, Haloperidol acceler-

treated compared to control cells (B–S6G). These

ates the centripetal movement of early endosomes.

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 137

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

M. bovis BCG with EEA1

(Haloperidol minus DMSO)

Colocalisation coef

M. bovis BCG with LBPA

p value = 0.00011

(Haloperidol minus DMSO)

Colocalisation coef

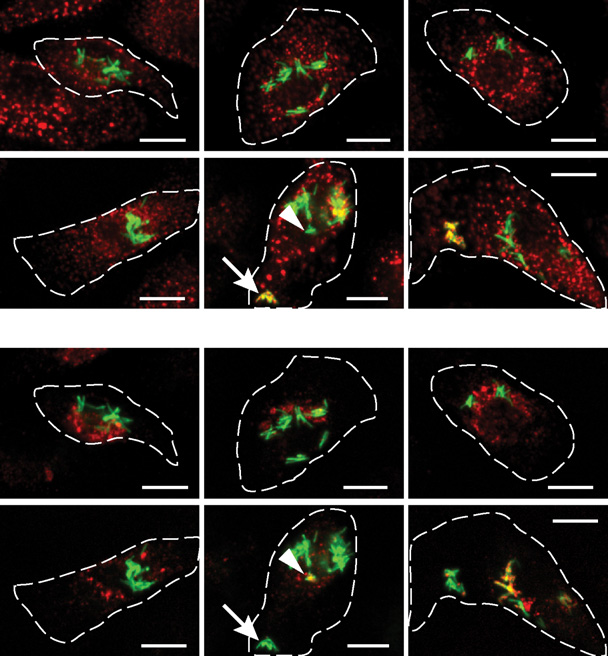

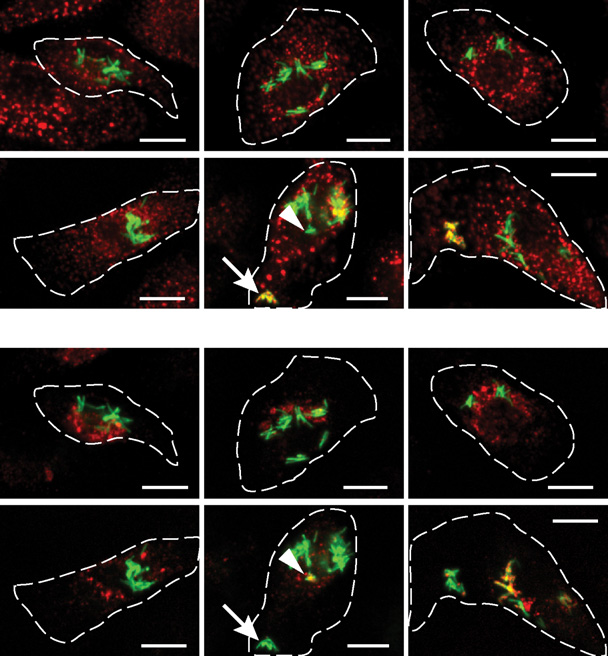

Figure 7. Haloperidol Induces Alterations in Intracellular Mycobacterial Trafficking(A and C) Representative images of M. bovis BCG-GFP-infected human primary macrophages treated with 10 mM Haloperidol for the indicated times andimmunostained for EEA1 (A) and LBPA (C). The outline of infected cells is shown in dashed lines. Scale bar, 10 mm. The presence of EEA1 and LBPA onmycobacterial phagosome, as indicated by arrows and arrowheads (at 20 min), respectively, is mutually exclusive.

(B and D) Quantification of colocalization of M. bovis BCG-GFP with EEA1 (B) and LBPA (D). A stringency threshold of 0.35 was used. Data are averaged fromabout 1,000 infected cells and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars are SEM. The p value denotes significance for theconsecutive points of the time series denoted by asterisks (see the

Second, we tested whether Haloperidol could lead to

increased delivery of the membrane-tethering and fusionmachinery to the arrested mycobacterial phagosome. Myco-

In this study, we developed a pipeline of experimental and

bacterial phagosomes contain Rab5, but not Rab7 (

computational methods to identify pharmacological modulators

and lack PI(3)P ),

of host cellular processes that trigger killing of intracellular myco-

which mediates the recruitment of various Rab5 effectors,

bacteria. First, we established a multiparametric image-based

including the membrane tethering factor early endosomal

assay to quantify mycobacterial survival in human primary

antigen 1 (EEA1) ). Therefore, myco-

macrophages. Second, we used a pharmacological approach

bacterial phagosomes lack EEA1 ). If Haloper-

to disrupt the host-pathogen equilibrium in favor of the host.

idol could restore such machinery, one would expect to see

Third, we developed computational methods to compare the

a small, transient increase in EEA1 on mycobacterial phago-

multiparametric profiles of chemicals with those of siRNAs, to

somes. We treated M. bovis BCG-infected cells with Haloper-

identify the cellular mechanisms underlying the antibacterial

idol for different times and quantified the colocalization of

activities of the compounds. Fourth, we validated the predictions

mycobacteria with EEA1 and LBPA. Whereas in control cells,

from such comparison on the three selected compounds and es-

as expected, mycobacterial phagosomes were devoid of

tablished that two of them modulate autophagy via distinct

EEA1 at all times (upper panels; B), in Halo-

mechanisms and the third one accelerates endocytic trafficking.

peridol-treated cells a small but significant fraction of EEA1

Our results demonstrate the predictive value of comparing quan-

localized to mycobacterial phagosomes 20–30 min posttreat-

titative multiparametric profiles from chemical and genetic

ment A, lower panels; Such an effect was

screens to decipher the cellular mechanisms of chemical action.

specific for Haloperidol, as it was not observed in cells treated

They further show that trafficking pathways can be modulated

with Nortriptyline and PE (data not shown). Moreover, in Halo-

pharmacologically to stimulate intracellular mycobacteria killing.

peridol-treated cells the colocalization of mycobacteria and

The key feature of our intracellular mycobacterial survival

LBPA increased with time C and 7D). Altogether,

assay is the multiplicity and reliability of parameters capturing

these data indicate that Haloperidol restores the delivery of crit-

various features of bacteria and host at high resolution. Interest-

ical components of the membrane-tethering machinery to the

ingly, most compounds in the selected hit cluster (M5) are not

mycobacterial phagosomes, thereby delivering mycobacteria

directly antimycobacterial. Although we cannot rule out

to lysosomes.

completely the possibility that the compounds may kill bacteria

138 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

directly within infected cells, we favor the interpretation that they

). PE may act at different stages, e.g., on the fusion

act by modulating the host for the following reasons. First, the

with lysosomes. Detailed characterization of the interactions of

M5 cluster showed very little overlap with the compounds which

Nortriptyline and PE with the autophagy machinery will lead to

act directly on bacteria. Second, the three selected compounds

a more precise understanding of their mode of action.

do not kill mycobacteria outside the host cell under the different

The identification of Haloperidol as an antimycobacterial

conditions tested. Third, they show similar effects on uninfected

compound provides proof of principle for the pharmacological

cells. Fourth, the effect of Nortriptyline and PE can be reverted by

modulation of endocytic trafficking as a means of boosting the

inhibiting a host cellular process (autophagy). Fifth, Nortriptyline

host defense system to clear intracellular pathogens. Most

showed strong phenotypic correlation with a structural analog,

importantly, our data imply that such an approach is feasible

Amitriptyline, in mycobacteria as well as endocytosis and auto-

without inducing overt toxicity to cells. Haloperidol leads to

phagy screens. Here, only structural analogs having a Tanimoto

faster degradation of cargo by accelerating transport from early

distance >0.9 were considered and

to late endocytic compartments. Previous work has identified

F–S2I). Sixth, Nortriptyline and PE enhance the acidity

both general design principles and molecular details of the

of lysosomes. This correlates with delivery of mycobacteria to

machinery underlying endosome biogenesis and progression

lysosomes and their survival. Additionally, standard antimyco-

that are relevant to the pharmacological properties of Haloper-

bacterial drugs showed weaker phenotypes compared to the

idol. First, transport of cargo (LDL) along the degradative route

selected compounds. Most likely, this is because our assay

entails a conversion from Rab5- to Rab7-positive endosomes

measures GFP fluorescence from mycobacteria that decays at

(). Such conversion is based on a cut-out switch

different rates, depending on whether the host degradation

() that requires the endosomal levels

machinery can be accelerated or not. In support of this, Rifam-

of Rab5 to pass a threshold value prior to triggering a feedback

picin did not show enhanced lysosomal acidity. Thus, our

loop causing its removal and substitution with Rab7. Second, our

screening platform has a bias for compounds that boost host

recent systems survey on endocytosis has revealed that the

mechanisms. Importantly, our data argue that such compounds

centripetal movement of endosomes previously observed by

are likely to be missed in a screen for antimycobacterial

quantitative live-cell imaging is a master

compounds outside the context of infected cells.

parameter that regulates several other properties of the early en-

Whereas cell-based high-content screens have several

dosome network, including cargo progression (

advantages over traditional target-based HT screens, under-

). Mycobacterium interferes with such a switch, keeping

standing the mechanism of action of the identified compounds

the phagosome in an arrested state. Remarkably, Haloperidol

is a critical bottleneck (One

exerts a positive influence on both centripetal movement of en-

possible approach is to identify genes that when silenced

dosomes and membrane recruitment of the Rab5 machinery.

produce a phenotype similar to that of small inhibitory molecules

By shifting the molecular composition of the mycobacterial

(However, there are significant caveats to

phagosome, Haloperidol counteracts the fine balance between

this approach: for example, small molecules usually act rapidly,

phagosome activity and maturation arrest, restoring maturation.

whereas RNAi is gradual and requires longer times, possibly

Thus, relatively subtle alterations in the general endocytic traf-

allowing the system to adapt to a new steady state. Moreover,

ficking machinery are sufficient to cause dramatic effects on

the biological activity of small molecules may result from the

intracellular mycobacterial survival.

modulation of multiple targets rather than

Our results revealed antimycobacterial properties for three ex-

specific ones as in RNAi, excluding off-target effects. We

isting drugs. While Nortriptyline is an antidepressant, PE and

reasoned that although it may prove difficult to identify targets

Haloperidol are antipsychotics. The serum concentrations

of small molecules by comparing the phenotypic profiles of

achieved in patients for these drugs are lower than the in vitro

chemicals and silenced genes, this approach may nevertheless

antibacterial IC50 (). In principle, they would

allow the identification of the cellular pathways affected, as long

have to be made significantly more potent or achieve signifi-

as the phenotypes are described with sufficient detail and spec-

cantly higher serum levels to be effective in antimycobacterial

ificity. Therefore, we captured the phenotypes through QMPIA,

therapy. However, it is difficult to compare the effectiveness of

and, by integrating chemical and functional genomics data

the drugs under the particular conditions used in vitro with their

sets, we differentiated hit compounds of the mycobacteria

pharmacokinetics properties in patients, and further studies are

screen into distinct groups on the basis of their phenotypes on

necessary to corroborate their antimycobacterial activity in vivo.

endocytosis. Using this strategy, we could show both computa-

Nevertheless, our work demonstrates that it is possible to find

tionally and experimentally that one of the groups is significantly

existing compounds with previously unrecognized antimyco-

enriched for modulators of autophagy, a well-known antimyco-

bacterial activity and mode of action. Interestingly, PE is also

bacterial cell-defense mechanism (

used as antiemetic and administered in patients with MDR-TB

). Remarkably, autophagy phenotypes could thus be

to alleviate ancillary symptoms of nausea and vomiting

identified using a general endocytosis assay.

The finding that three neuromodulators are en-

Nortriptyline and PE influence autophagy differently. Whereas

dowed with membrane trafficking and antimycobacterial activity

Nortriptyline induces the formation of autophagosomes, PE

suggests that compounds can exert diverse biological effects

slows down autophagic flux. The basal rate of autophagy may

depending on the cellular context analyzed. Such influences

be sufficient to accumulate autophagosomes in the presence

are typically neglected in target-based screenings. Repurposing

of PE. These autophagosomes progressively acidify over time

existing drugs for additional applications could thus open new

and become competent for mycobacteria degradation (

avenues and lead to rapid therapeutic advances

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 139

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

However, it is not excluded that the effects on intracellular

score >3 were considered hits. The screen was repeated twice (Z0 factors

transport highlighted in this study may even be part of the mech-

are 0.85 and 0.9 for each run). Hits from both runs were combined.

anism of action of the compounds in neuromodulation. The

High-Content Autophagy Assay

mechanistic clues obtained here open the possibility of exploring

HeLa cells were treated with the compounds at a final concentration of 10 mM,

the role of cellular processes, i.e., autophagy and modulation of

incubated for 4 hr, fixed with 3.7% PFA, and immunostained with anti-LC3

endocytic trafficking, in the context of their original therapeutic

antibody (clone PM036, MBL Labs). Cells were counterstained by DAPI and

use. Indeed, many tricyclic antidepressants, regarded as medi-

Cell Mask blue, imaged, and analyzed as described above.

ators of neurotransmitter signaling, show significant effects onautophagy (). Synergistic

Dose-Response Curves

activities of such compounds with other antibacterial and

To calculate IC50 for mycobacterial survival, human primary monocyte-derivedmacrophages were infected with M. bovis BCG-GFP, treated with different

immune modulators, such as IFN-g, could be exploited to yield

concentrations of the compounds for 48 hr, and fixed. For autophagy assay,

more potent pharmacological interventions. Finally, the methods

the same preparation of cells was treated with the compounds for 2 hr, fixed,

described here can be adapted to other diseases where host cell

and immunostained for LC3. Cells were imaged and analyzed as described.

processes need to be targeted. The compounds identified maytherefore also be effective against pathogens using similar

M. tuberculosis CFU Assay

Human primary macrophages were infected with virulent M. tuberculosis strainH37Rv and two different clinical isolates (CS1 and CS2) for 1 hr at moi 1:10,washed, treated with Amikacin (200 mg/ml) for 45 min, washed again, and

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

treated with the compounds. Cells were lysed after 48 hr with 0.05% SDSand plated in multiple dilutions on 7H11 agar plates. Colonies were counted

High-Content Screen for Intracellular Mycobacteria Survival

after incubation at 37�C for 3 weeks.

Human primary monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with M. bovisBCG-GFP for 1 hr at moi of 1:10, washed extensively (Biotec EL406). After

Electron Microscopy

adding the compounds (10 mM) (Beckman Fxp automatic workstation), cells

Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde followed by postfixation in ferrocy-

were incubated for 48 hr, fixed with 3.7% PFA (Sigma), stained with 1 mg/ml

anide-reduced osmium following standard protocols ()

DAPI and 3 mg/ml Cell Mask Blue (Invitrogen), and imaged using the automated

and embedded with epon. Then 70 nm thin sections were cut on a Leica ultra-

spinning disk confocal Opera (Perkin Elmer). See the

microtome, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate following classical

for details.

procedures, and imaged on a 100 kV Tecnai 12 TEM microscope. For areameasurements, several overlapping high-magnification images covering the

Data Analysis: Density-Based Clustering

whole cell were acquired, and a montage was generated using ImageJ.

Multiparametric profiles from the chemical screen were clustered usingdensity-based clustering algorithm with von Mises-Fisher kernel used for

Live-Cell Imaging

density estimate (N.S., T. Galvez, C. Collinet, G.M., M.Z., and Y.K., unpub-

A431 cells stably expressing GFP-Rab5 were treated with 10 mM Haloperidol

lished data). Clustering was performed varying the kernel concentration

for 2 hr and imaged live using Zeiss Duo scan microscope at 0.098 s/frame for

parameter k. For every data set, the number of clusters obtained stabilized

2 min. Individual endosomes were identified and tracked over time as

within a k range of 10–150. Further increase of k would not lead to an increase

described (). To calculate mean square displacement, endoso-

in the number of clusters. For each data set, a cluster was manually selected at

mal tracks were first iteratively divided into nonoverlapping equal time intervals

the first value of k that produced clusters that were stable in number and size.

from 0.1 to 70 s, and their displacements were computed for each interval.

k values for the mycobacteria and endocytosis screens were 30 and 90,

Next, the square of displacement for all endosomal tracks for a given condition

was averaged and plotted as a function of the time interval. In such a curve,early endosomes show a characteristic biphasic behavior, which we refer to

Integrating Chemical and Genetic Screens

as short timescale and long timescale movements.

Representative profiles of the two endocytosis subclusters were generated byaveraging the profiles of individual compounds in each subcluster. For these

Estimation of p Value for Time Series

two profiles, we assembled a list of genes from the endocytosis screen (

The null hypothesis tested is that deviation of a sequence of N measurements

) that had a Phenoscore >0.95 and a Pearson correlation of 0.7.

from zero is the result of normally distributed noise. Given that every measure-

These lists were subjected to gene annotation enrichment analysis using

ment i in the series has a value Di and variance s2i, we computed the probability

a standard hypergeometric test. Gene annotations were obtained from Gene

of the null hypothesis (p value) as

Ontology and KEGG Pathway databases.

Intracellular Mycobacterial Trafficking Assay

pvalue = 1 B

2 @1 � erf@ 2@P

Human primary monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with M. bovis

BCG-GFP and stained for lysotracker red or LBPA as markers of lateendosomes and lysosomes (Colocalizations were scored over a range of stringency thresholds

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

varying from 0 (most relaxed) to 1 (most stringent).

Supplemental Information includes six figures, two movies, three tables,

Alamar Blue Screen for Antibacterial Compounds

Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and Supplemental References and

To mid-log phase M. bovis BCG-GFP seeded into 384-well plates (OD

can be found with this article at

0.03) in a volume of 90 ml 7H9, compounds were added to a final concentrationof 10 mM. DMSO and Amikacin (200 mg/ml) were included as negative and

positive controls, respectively. Plates were incubated at 37�C for 4 days, fol-lowed by addition of 10 ml of 1:1 mix of alamar blue (serotec) and 10%

We thank Dr. J. Pieters (Biozentrum, University of Basel) for M. bovis BCG-GFP

Tween-80. After 24 hr at 37�C, fluorescence was read in the Tecan Pro (Ex

strain, Dr. J. Gruenberg (University of Geneva) for anti-LBPA antibody, Drs. A.

535 nm; Em 590 nm). Analysis was done per plate. Compounds with a Z

Ballabio and D. Medina (TIGEM, Naples) for HeLa mRFP-GFP-LC3 stable

140 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

clone, Drs. E. Jacobs and S. Monecke (TU, Dresden) for providing

work to infer endosomal network dynamics from quantitative image analysis.

M. tuberculosis strains, and Dr. E. Fava (DKNZ, Bonn) for the initial work. We

Curr. Biol. 22, 1381–1390.

are indebted to N. Tomschke, M. Stoeter, A. Giner, S. Seifert, C. Moebius,

Fratti, R.A., Backer, J.M., Gruenberg, J., Corvera, S., and Deretic, V. (2001).

C. Andree, and the HT-TDS for expert technical assistance; I. Poser and

Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rab5 effectors in phagosomal

BAC recombineering facility for HeLa LC3-GFP BAC and HeLa Rab5-GFP

biogenesis and mycobacterial phagosome maturation arrest. J. Cell Biol.

BAC cell lines; the High-Performance Computing Center at TUD, M. Chernykh,

and the computer department for expert IT assistance; and E. Perini, M.

Gutierrez, M.G., Master, S.S., Singh, S.B., Taylor, G.A., Colombo, M.I., and

McShane, and K. Simons for critical comments on the manuscript. This

Deretic, V. (2004). Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and

work was supported by EU-FP7-funded projects NATT, PHAGOSYS, APO-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119,

SYS, and the Max-Planck Society.

Received: August 2, 2012

Huang, R., Southall, N., Wang, Y., Yasgar, A., Shinn, P., Jadhav, A., Nguyen,

Revised: November 2, 2012

D.T., and Austin, C.P. (2011). The NCGC pharmaceutical collection: a compre-

Accepted: January 3, 2013

hensive resource of clinically approved drugs enabling repurposing and chem-

Published: February 13, 2013

ical genomics. Sci. Transl. Med. 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.

3001862, 80ps16.

Imming, P., Sinning, C., and Meyer, A. (2006). Drugs, their targets and thenature and number of drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 821–834.

Alix, E., Mukherjee, S., and Roy, C.R. (2011). Subversion of membrane trans-

Jayachandran, R., Sundaramurthy, V., Combaluzier, B., Mueller, P., Korf, H.,

port pathways by vacuolar pathogens. J. Cell Biol. 195, 943–952.

Huygen, K., Miyazaki, T., Albrecht, I., Massner, J., and Pieters, J. (2007).

Armstrong, J.A., and Hart, P.D. (1971). Response of cultured macrophages to

Survival of mycobacteria in macrophages is mediated by coronin 1-dependent

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with

activation of calcineurin. Cell 130, 37–50.

phagosomes. J. Exp. Med. 134, 713–740.

Jayaswal, S., Kamal, M.A., Dua, R., Gupta, S., Majumdar, T., Das, G., Kumar,

Behar, S.M., Divangahi, M., and Remold, H.G. (2010). Evasion of innate immu-

D., and Rao, K.V. (2010). Identification of host-dependent survival factors for

nity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: is death an exit strategy? Nat. Rev.

intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis through an siRNA screen. PLoS

Microbiol. 8, 668–674.

Bucci, C., Parton, R.G., Mather, I.H., Stunnenberg, H., Simons, K., Hoflack, B.,

Karnovsky, M. (1971). Use of ferrocyanide-reduced osmium tetroxide in

and Zerial, M. (1992). The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in

electron microscopy. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the

the early endocytic pathway. Cell 70, 715–728.

American Society for Cell Biology.

Caspi, A., Granek, R., and Elbaum, M. (2002). Diffusion and directed motion in

Keane, J., Remold, H.G., and Kornfeld, H. (2000). Virulent Mycobacterium

cellular transport. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 66, 011916.

tuberculosis strains evade apoptosis of infected alveolar macrophages.

J. Immunol. 164, 2016–2020.

Chen, M., Gan, H., and Remold, H.G. (2006). A mechanism of virulence: viru-

Kimura, S., Noda, T., and Yoshimori, T. (2007). Dissection of the autophago-

lent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, but not attenuated H37Ra,

some maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-

causes significant mitochondrial inner membrane disruption in macrophages

tagged LC3. Autophagy 3, 452–460.

leading to necrosis. J. Immunol. 176, 3707–3716.

Klionsky, D.J., Abeliovich, H., Agostinis, P., Agrawal, D.K., Aliev, G., Askew,

Christoforidis, S., McBride, H.M., Burgoyne, R.D., and Zerial, M. (1999). The

D.S., Baba, M., Baehrecke, E.H., Bahr, B.A., Ballabio, A., et al. (2008).

Rab5 effector EEA1 is a core component of endosome docking. Nature 397,

Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy

in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4, 151–175.

Collinet, C., Sto¨ter, M., Bradshaw, C.R., Samusik, N., Rink, J.C., Kenski, D.,

Kobayashi, T., Stang, E., Fang, K.S., de Moerloose, P., Parton, R.G., and

Habermann, B., Buchholz, F., Henschel, R., Mueller, M.S., et al. (2010).

Gruenberg, J. (1998). A lipid associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome

Systems survey of endocytosis by multiparametric image analysis. Nature

regulates endosome structure and function. Nature 392, 193–197.

Koul, A., Herget, T., Klebl, B., and Ullrich, A. (2004). Interplay between myco-

Del Conte-Zerial, P., Brusch, L., Rink, J.C., Collinet, C., Kalaidzidis, Y., Zerial,

bacteria and host signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 189–202.

M., and Deutsch, A. (2008). Membrane identity and GTPase cascades regu-lated by toggle and cut-out switches. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 206. http://dx.doi.

Kuijl, C., Savage, N.D., Marsman, M., Tuin, A.W., Janssen, L., Egan, D.A.,

Ketema, M., van den Nieuwendijk, R., van den Eeden, S.J., Geluk, A., et al.

(2007). Intracellular bacterial growth is controlled by a kinase network around

Desjardins, M., Huber, L.A., Parton, R.G., and Griffiths, G. (1994). Biogenesis

PKB/AKT1. Nature 450, 725–730.

of phagolysosomes proceeds through a sequential series of interactions withthe endocytic apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 124, 677–688.

Kumar, D., Nath, L., Kamal, M.A., Varshney, A., Jain, A., Singh, S., and Rao,K.V. (2010). Genome-wide analysis of the host intracellular network that regu-

Dhandayuthapani, S., Via, L.E., Thomas, C.A., Horowitz, P.M., Deretic, D., and

lates survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 140, 731–743.

Deretic, V. (1995). Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expressionand cell biology of mycobacterial interactions with macrophages. Mol.

Laplante, M., and Sabatini, D.M. (2012). mTOR signaling in growth control and

Microbiol. 17, 901–912.

disease. Cell 149, 274–293.

Dyer, M.D., Murali, T.M., and Sobral, B.W. (2008). The landscape of human

Matsuzawa, T., Kim, B.H., Shenoy, A.R., Kamitani, S., Miyake, M., and

proteins interacting with viruses and other pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 4, e32.

Macmicking, J.D. (2012). IFN-g elicits macrophage autophagy via the p38

MAPK signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 189, 813–818.

Eggert, U.S., Kiger, A.A., Richter, C., Perlman, Z.E., Perrimon, N., Mitchison,

Pieters, J. (2008). Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the macrophage: main-

T.J., and Field, C.M. (2004). Parallel chemical genetic and genome-wide

taining a balance. Cell Host Microbe 3, 399–407.

RNAi screens identify cytokinesis inhibitors and targets. PLoS Biol. 2, e379.

Ponpuak, M., Davis, A.S., Roberts, E.A., Delgado, M.A., Dinkins, C., Zhao, Z.,

Virgin, H.W., 4th, Kyei, G.B., Johansen, T., Vergne, I., and Deretic, V. (2010).

Fairn, G.D., and Grinstein, S. (2012). How nascent phagosomes mature to

Delivery of cytosolic components by autophagic adaptor protein p62 endows

become phagolysosomes. Trends Immunol. 33, 397–405.

autophagosomes with unique antimicrobial properties. Immunity 32, 329–341.

Foret, L., Dawson, J.E., Villasen˜or, R., Collinet, C., Deutsch, A., Brusch, L.,

Poser, I., Sarov, M., Hutchins, J.R., He´riche´, J.K., Toyoda, Y., Pozniakovsky,

Zerial, M., Kalaidzidis, Y., and Ju¨licher, F. (2012). A general theoretical frame-

A., Weigl, D., Nitzsche, A., Hegemann, B., Bird, A.W., et al. (2008). BAC

Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc. 141

Cell Host & Microbe

Killing M. tuberculosis by Targeting the Host

TransgeneOmics: a high-throughput method for exploration of protein function

Seglen, P.O., and Gordon, P.B. (1982). 3-Methyladenine: specific inhibitor of

in mammals. Nat. Methods 5, 409–415.

autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc.

Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 1889–1892.

Regenthal, R., Krueger, M., Koeppel, C., and Preiss, R. (1999). Drug levels:therapeutic and toxic serum/plasma concentrations of common drugs.

Settembre, C., Di Malta, C., Polito, V.A., Garcia Arencibia, M., Vetrini, F., Erdin,

J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 15, 529–544.

S., Erdin, S.U., Huynh, T., Medina, D., Colella, P., et al. (2011). TFEB linksautophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science 332, 1429–1433.

Rink, J., Ghigo, E., Kalaidzidis, Y., and Zerial, M. (2005). Rab conversion asa mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell 122, 735–749.

Shubin, H., Sherson, J., Pennes, E., Glaskin, A., and Sokmensuer, A. (1958).

Prochlorperazine (compazine) as an aid in the treatment of pulmonary tubercu-

Rossi, M., Munarriz, E.R., Bartesaghi, S., Milanese, M., Dinsdale, D., Guerra-

losis. Antibiotic Med. Clin. Ther. 5, 305–309.

Martin, M.A., Bampton, E.T., Glynn, P., Bonanno, G., Knight, R.A., et al.

Swinney, D.C., and Anthony, J. (2011). How were new medicines discovered?

(2009). Desmethylclomipramine induces the accumulation of autophagy

Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 507–519.

markers by blocking autophagic flux. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3330–3339.

Vergne, I., Chua, J., Lee, H.H., Lucas, M., Belisle, J., and Deretic, V. (2005).

Russell, D.G. (2001). Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today, and here

Mechanism of phagolysosome biogenesis block by viable Mycobacterium

tomorrow. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 569–577.

tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4033–4038.

Schmid, S.L., and Cullis, P.R. (1998). Membrane sorting. Endosome marker is

Zschocke, J., Zimmermann, N., Berning, B., Ganal, V., Holsboer, F., and

fat not fiction. Nature 392, 135–136.

Rein, T. (2011). Antidepressant drugs diversely affect autophagy pathways

Schwegmann, A., and Brombacher, F. (2008). Host-directed drug targeting of

in astrocytes and neurons—dissociation from cholesterol homeostasis.

factors hijacked by pathogens. Sci. Signal. 1, re8.

142 Cell Host & Microbe 13, 129–142, February 13, 2013 ª2013 Elsevier Inc.

Source: https://publications.mpi-cbg.de/Sundaramurthy_2013_5321.pdf

Alcohol And other drug Copyright © 2009 State of Victoria. 2nd edition printed 2012.ISBN: 978 1 74001 001 6Reproduced with permission of the Victorian Minister for Mental Health. Unauthorised reproduction and other uses comprised in the copyright are prohibited without permission.Copyright enquiries can be made to Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre,

growingfutures case study series 18. Health Enhancing Products from New Zealand plants Our developement of health enhancing products have three important factors: 1. New Zealand's reputation continues to grow internationally as a source of clean and green raw materials, including customised high-tech ingredients that are sold to nutritional manufacturers around the world.