Dec2003community.pdf

54. Summerson JS, Konen JC, Dignan MB. Race related differences in metabolic control among

66. Robinson CH, Lawler MR, Chenoweth WL,

et al. Normal and Therapeutic Nutrition. 7th ed New

adults with diabetes.

S Afr Med J 1992;

85: 953-956.

York: Macmillan, 1986: 759.

55. Rasmussen OW, Gregersen S, Dorup J,

et al. Day to day variation of blood glucose and

67. Thornburn AW, Brand JC, Truswell AS. The glycaemic index of foods.

Med J Aust 1986;

144:

insulin responses in type 2 diabetic subjects after starch-rich meal.

Diabetes Care 1992;

15: 522-

68. Jackson RA, Blick PM, Matthews JA,

et al. Comparison of peripheral glucose uptake after oral

56. Castillo MJ, Scheen AJ, Jandrian B,

et al. Relationship between metabolic clearance rate of

glucose loading and a mixed meal.

Metabolism 1983;

32: 706-710.

insulin and body mass index in a female population ranging from anorexia nervosa to severe

69. Porte D, Sherwin RS.

Ekkenberg and Rifkin's Diabetes Mellitus: Theory and Practice. 5th ed. USA:

obesity.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1994;

18: 47-53.

Appleton and Lange, 1997: 366.

57. Marion JF. Nutritional care in diabetes mellitus and reactive hypoglycemia. In: Krause MV,

70. Wolever TMS, Jenkins DJA, Jenkins AL. The glycemic index: methodology and clinical

Mahan LK, eds

. Krause's Food, Nutrition and Diet Therapy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders,

implications.

Am J Clin Nutr 1991;

54: 846-854.

1984: 479-509.

71. Bantle JP, Laine DC, Castle GW,

et al. Postprandial glucose and insulin responses to meals

58. Weyman-Daum M, Fort P, Recker B,

et al. Glycemic response in children with insulin-

containing different carbohydrates in normal and diabetic subjects.

N Engl J Med 1983;

309: 7-

dependent diabetes mellitus after high- or low-glycemic-index breakfast.

Am J Clin Nutr 1987;

46: 798-803.

72. Nuttal FQ, Moorandian AD, DeMarais R,

et al. The glycemic effect of different meals

59. Jenkins DJA, Wolever TMS, Jenkins AL,

et al. The glycaemic index of foods tested in diabetic

approximately isocaloric and similar in protein, carbohydrate and fat content as calculated

patients; a new basis for carbohydrate exchange favouring the use of legumes.

Diabetologia

using the ADA exchange lists.

Diabetes Care 1983;

6: 432-435.

1983; 24: 257-264.

73. Gannon MC, Nuttal FQ, Krezowski PA,

et al. The serum insulin and plasma glucose response

60. Inoescu-Tîrgoviste C, Popa E, Sîntu E,

et al. Blood glucose and plasma insulin responses to

to milk and fruit products in type 2 (non-insulin dependant) diabetic patients.

Diabetologia

various carbohydrates in type 2 (non-insulin dependant) diabetes.

Diabetologia 1983; 14: 80-84.

1986;

29: 784-791.

61. Venter CS, Vorster HH, Van Rooyen A,

et al. Comparison of the effects of maize porridge

74. Laine DC, Thomas W, Levitt MD,

et al. Comparison of predictive capabilities of diabetic

consumed at different temperatures on blood glucose, insulin and acetate levels in healthy

exchange lists and glycemic index of foods.

Diabetes Care 1987;

10: 387-394.

volunteers.

South African Journal of Food Science and Nutrition 1990;

2: 2-5.

75. Reaven GM, Chen Y-DI, Golay A,

et al. Documentation and hyperglucagonemia throughout

62. Truswell AS. Glycaemic index of foods.

Eur J Clin Nutr 1992;

46S: S91 - S101.

the day in nonobese and obese patients with non-insulin dependant diabetes mellitus.

J Clin

63. Thompson DG, Wingate DL, Thomas M,

et al. Gastric emptying as a determinant of the oral

Endocrinol Metab 1987;

64: 106-110.

glucose tolerance test.

Gastroenterology 1982;

82: 51-55.

76. Coulston AM, Hollenbeck CB, Swiskocki ALM,

et al. Effect of source of dietary carbohydrate

64. Krezowski PA, Nuttal FQ, Gannon MC,

et al. Insulin and glucose responses to various starch-

on plasma glucose and insulin responses to mixed meals in subjects with NIDDM.

Diabetes

containing foods in type 2 diabetic subjects.

Diabetes Care 1987;

10: 205-212.

Care 1987;

10: 395-400.

65. Hunt SM, Groff JL.

Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. New York: West, 1990.

77. Hollenbeck CB, Coulston AM, Reaven GM. Glycemic effects of carbohydrates: a different

perspective.

Diabetes Care 1986;

9: 641-647.

A community-based growth monitoring model to

complement facility-based nutrition and health practices in

a semi-urban community in South Africa

Serina E Schoeman, Muhammad A Dhansay, John E Fincham, Ernesta Kunneke, A J Spinnler Benadé

Objective. To assess the feasibility of a community-based

monitoring system. The community-based growth

growth monitoring model in alleviating the shortcomings in

monitoring system increased growth monitoring coverage of

health and nutrition surveillance of preschool-aged children

preschool children by more than 60%. Attendance of

as practised by the health services.

preschool children aged 12 months and older varied between

Method. Baseline community and health facility practice

10% and 14% at the health facility practice compared with 80

surveys and interactive workshops with the community were

- 100% in the community-based growth monitoring system.

conducted before the study. Eleven women were trained to

This made the system more conducive for monitoring and

drive the community-based growth monitoring project.

targeting of malnourished children for health and nutrition

Health facility practice information was collected before and

after establishment of the community-based growth

Conclusion. The community-based growth monitoring model

monitoring system.

demonstrated that community participation and mobilisation

Results. The health facility practice reached 12 - 26% of the

can increase preschool child growth monitoring coverage

preschool population per month compared with 70 - 100%

extensively and contribute to improved health and nutrition

per 3-week session in the community-based growth

Nutritional Intervention Research Unit, Medical Research Council, Parow, W Cape

Parasitology Group, Medical Research Council, Parow, W Cape

Serina E Schoeman, BA Cur

John E Fincham, BVSc

Muhammad A Dhansay, FCP

Department of Dietetics, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, W Cape

A J Spinnler Benadé, DSc

Ernesta Kunneke, MSc

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4

SAJCN

Inadequacies in preschool child growth monitoring (GM)

perceptions of nutrition, while the CBGM model was the action

coverage at health facility practices (HFPs) have been described

component that developed after analysis of the baseline survey

in several studies.1,2 Maternal perceptions of HFPs, and service

data presented at a ZOPP (Ziel Orientierte Projekt Planung or

providers emphasising a curative approach are key factors

objective oriented project planning) workshop.10 The baseline

influencing health care coverage of the preschool child. In the

survey and the CBGM model will be discussed simultaneously

absence of disease or clinical symptoms, mothers regard the

to illustrate the impact of the model.

childhood immunisation schedule as the main reason forvisiting the HFP. The curative approach emphasised by the

HFP fosters the perception among people that health care

The study population consisted of ± 250 children aged 0 - 72

equals curative care, which is a fallacy.3 Health care is often

months and their mothers, living in Langebaan, a small urban

associated with ‘the provision of doctors, drugs, ambulances

town on the west coast of the Western Cape, 136 km from Cape

and hospitals', while preventive measures are less appreciated.3

Town. It has a population of approximately 4 000 people, and a

After primary completion of the childhood immunisation

preschool population of ± 350 children. Children were

schedule at 9 months, GM and preschool attendance decline

identified for the project using registrations from the HFP, the

drastically at HFPs. HFPs are biased in favour of children

community survey and birth records. The annual birth rate is

between 0 and 24 months of age, and do not assess height-for-

approximately 45 - 50 births and the prevalence of low birth

weight (less than 2 500 g) remains at between 17% and 22%.

Underweight, which peaks after 18 months, and stunting are

Most inhabitants earn their living through fishing and have a

often not detected because of sporadic attendance and poor

low income. The town is also a big tourist attraction. A small,

GM at HFPs.1,2,4,5 Strategies such as GM and growth promotion,

richer group in the town generates income mainly through

oral rehydration therapy, breast-feeding, food supplementation

accommodating tourists in holiday homes or guesthouses.

and education of women to promote and strengthen the healthfacility-based nutrition component, are therefore seriously

Community baseline survey

The survey was conducted over 7 months.

A community-based growth monitoring (CBGM) system in

rural areas with inadequate health services appears to be a

viable cost-effective option for monitoring growth, nutritional

Eleven women from the local community were trained by staff

status and health of children.9 To determine whether such a

of the Nutritional Intervention Research Unit (NIRU) of the

model could also be implemented in an urban setting with

Medical Research Council (MRC) to administer questionnaires

established health systems, required further investigation. An

to determine caregivers' perceptions on disease, nutrition and

opportunity to pursue this issue arose when the Child Welfare

health practices. The information was obtained from parents or

Society requested assistance from the Nutritional Intervention

guardians of preschool children during house-to-house visits.

Research Unit (NIRU) of the Medical Research Council (MRC),

Breast-feeding information was obtained in a separate study.

because of perceived problems of malnutrition amongpreschool children in towns on the west coast, South Africa.

Langebaan was selected as a suitable community that could beresearched to identify possible causal factors for the suspected

The women's training also involved anthropometry and GM.

nutritional situation. The purpose of this study was to

Children were weighed with minimal clothing on an electronic

determine whether a CBGM model could be established in an

load cell scale to the nearest 0.05 kg, and height and length

urban setting to alleviate shortcomings of the local HFP in

were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using wooden measuring

terms of health and nutrition surveillance of preschool

boards. Recumbent length for children under 2 years old, and

measurements in the standing position for children 2 years andolder were obtained.11,12

A calibrated 10 kg weight was used to assess the accuracy of

Materials and methods

the scales before GM sessions.

Study design

A member of the research team randomly selected children

To develop the CBGM model a cross-sectional baseline survey

for cross-checking. Anthropometric information was used to

was done and the results were used in conjunction with the

calculate z-scores using Epi-Info version 6.04.

community's perceptions of priority needs. The baseline surveycomprising community-based and health facility-based

Health facility practices survey

components, was conducted to assess preschool children's

The survey comprising preschool children attending the HFP

nutritional status, nutrition and health practices and maternal

was conducted over 12 months. The HFP survey ran

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4 SAJCN

concurrently with the CBGM model for the last 5 months of the

immunisation schedule identified from the RTHC, complaints

year. Information on preschool child attendance, disease

from mothers of a child being sick or chronically ill, and

prevalence and health and nutrition practices was obtained

suspected problems of child neglect or abuse. The

from the professional nurse as part of the information routinely

infrastructure of the CBGM system allowed for additional

collected at the HFP.

activities such as nutrition and health education, biochemical

The information was recorded on structured sheets specially

and parasitological analysis, management of iron deficiency

drawn up by the researcher. Mother's reason for visiting the

and worm infection, and blanket deworming of preschool

HFP, procedures performed, group or individual health

children, which will be reported separately.

education topics and outcomes of visit were recorded for eachchild. Client status such as visitor, first or follow-up visit, was

also indicated. Food supplementation data were obtained froma register held at the HFP and growth plotting practices were

Community baseline survey

observed from children's road-to-health cards (RTHCs).

Maternal reasons for visiting the HFP

Information was calculated monthly by listing items according

Sixty-three per cent of mothers indicated that visiting the HFP

to a coding system.

after completion of the immunisation schedule was onlynecessary if the child was sick, while 17% said they would

ZOPP workshop and the establishment of the

attend for general assessments, information, or weighing

CBGM model

children, and 20% did not deem it necessary at all.

The ZOPP workshop was facilitated by the NIRU as the

process allows maximum involvement, and an equal

Seventy-nine per cent of the mothers initiated breast-feeding,

opportunity for all participants to determine priority needs and

but none of the infants was exclusively breast-fed. Formula

to participate in the planning and implementation of an

feeding was introduced soon after birth and solids from 0.5 -1.3

intervention project. The workshop participants comprised

months of age.

stakeholders from the Departments of Health and Education,the local municipality, non-governmental organisations, health

committees, women's committees, reconstruction and

Maternal perceptions on food supplementation were not

development programme committees, and NIRU staff.

Information collected during the baseline survey was used as astarting point and combined with the participant's information

GM practices and anthropometry

to construct a problem tree, and to develop a causal and

Z-scores below –2 standard deviations (SD) of the National

objective model. This process pre-empted the establishment of

Centre for Health Statistics reference median indicated stunting

the CBGM model.

prevalence rates of 13%, underweight 7% and wasting 2.2%.

Women who were originally trained to do anthropometry

Although 60% of the mothers could recognise a downward

and GM for the baseline community survey, volunteered to

growth curve and associated it with a problem or the child

manage the CBGM system. Five health stations to serve as a

being sick, 81% of the mothers were not familiar with the

facility for preschool CBGM were volunteered by

concept of GM.

representatives of a church, school, crèches, the municipality

HFP survey

and individual families in the community.

Mothers' reasons for visiting the HFP

An appointment system was used to accommodate mothers

in geographical areas nearest to the CBGM points to ensure

Weighing of children was the most important reason for

effective functioning. Appointments were confirmed 1 week

visiting the HFP (41%) and peaked in the 0 - 23-month-old

before the GM sessions. GM was performed 4-monthly, while

group. Ill health was the second most important reason (31%),

nutritionally at-risk children detected during the GM sessions

and peaked in the 12 - 23-month-old group. Childhood

were monitored more than once a month and referred to the

immunisation was the third most important reason (23%), and

HFP for further management. Information was collected and

exceeded ill health only during the first 12 months. Only 5% of

128 entered into a separate folder for each child. A simplified

the parents mentioned health assessments, screenings for

growth chart was used for documentation, plotting and

tuberculosis, or general health information as primary reasons

interpretation of weight to avoid interfering with the RTHC

for visiting the HFP. From 48 months, 6 out of 8 children visit

used at the HFP. Nutritional risk criteria at the CBGM included

the HFP mainly due to ill health. These findings are biased in

weight and height below the 3rd percentile (scale of reference

favour of mothers whose infants were in the 0 - 12-month-age

at the HFP), low birth weight, growth faltering, incomplete

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4 SAJCN

Breast-feeding practices

HFP information regarding breast-feeding practices wasinconsistently recorded. Individual breast-feeding counsellingof mothers was indicated mainly if the mother experiencedproblems with her breasts or with breast-feeding. Exclusivebreast-feeding practices were not indicated.

Protein energy malnutrition scheme food supplement at the

HFP

Results indicated that only 21 out of 36 preschool children(58%) with weight below the 3rd percentile and growthfaltering were entered in the PEM scheme register before, and afurther 11 after, referral from the CBGM system. Of the 32children entered in the 1996 PEM scheme register, 37.5%received the food supplement more than once, while 62.5%received it only once. The results also indicated that only 12.5%received the food supplement at uninterrupted monthlyintervals for ± 3 consecutive months, while 87.5% received less

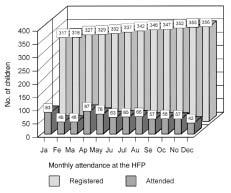

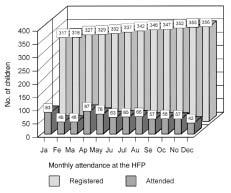

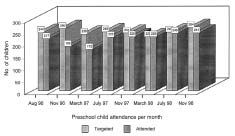

Fig. 1. Coverage of preschool children at the health facility practice

than four food supplements at intervals varying from 2 to 10

(January - December 1996 Langebaan).

GM practices

The ZOPP workshop and the CBGM model

A growth chart study of 51 randomly selected RTHCs

The establishment of the CBGM system that was pre-empted

indicated an average of 5 weight plots between 0 and 6 months

by the ZOPP workshop resulted in sustained GM and health

(1 or no plot per month), 2 plots between 7 and 12 months,

and nutrition surveillance of preschool children. The model

1 plot between 13 and 24 months and 1 or no plots per year

complemented the existing HFP while primary health care was

after the age of 24 months. Height was mainly measured at

managed in the usual way by nursing staff under the

birth and height plotting was not required on the RTHC.

governance of the local authority. Although the CBGM system

Preschool child coverage at the HFP

approach was research-orientated, while the HFP was service-orientated, these findings could serve to enhance policy

Age-specific attendance for preschool children after the age of

12 months varied between 0 and 10, 1 and 8, and 2 and 6 permonth over the respective months and attendance in the 0 - 12-

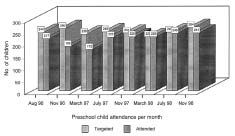

Coverage of preschool children in the CBGM system

month age group tended to decline over the 4-monthly

Preschool coverage in the CBGM system varied between 71%

intervals as the year proceeded (Table I). The preschool

and 100%, sustaining a high average coverage of 80 - 85% over

attendance of 12 - 26% per month was constant throughout the

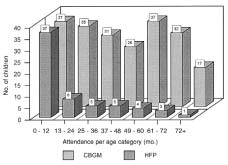

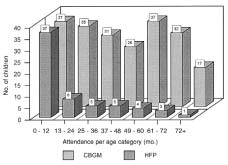

a period of 3 years (Fig. 2). Age-specific attendance after the

year. Average monthly attendance was ± 17% (Fig. 1).

age of 12 months varied between 17 and 37 children per sessionin the CBGM system compared with 1 - 8 children per monthat the HFP (Fig. 3).

Table I. Age-specific coverage of preschool children at the HFP

(April, August, December 1996, Langebaan)

Number of chidren

attending the HFP

* Best attendance pattern.

† Worst attendance pattern.

Fig. 2. Coverage of preschool children in the CBGM system (August1996 - November 1998).

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4 SAJCN

preschool visits, which impact negatively on childhoodnutrition and health as well as health care practices. Thisresults in the HFPs missing the majority of mothers shortlyafter weaning is initiated, and the child's risk of malnutritionand infectious diseases increasing.

HFP and GM practices

Irregular and inaccurate measuring of weight and height andpoor plotting and interpretation of children's weight at theHFPs is a reality.1,2,5,15,16 This results in under-detection ofretarded growth and underweight. Weighing a child withoutplotting is often regarded as synonymous with GM, whilefailing to plot weight deprives nursing staff of the opportunityto promote child growth and development.17,18 Lack of heightassessments deprives stunted children from being targeted for

Fig. 3. Comparison of age-specific attendance at the HFP and in the

appropriate interventions. Discontinuous GM of preschool

CBGM system (August 1996).

children hampers detection and targeting of nutritionally at-

GM practices and anthropometry (November 1996,

risk children, and therefore control of malnutrition and

November 1997 and November 1998)

infectious diseases.

The CBGM system was successful in nutrition surveillance of

Food and iron supplementation and breast-feeding

preschool children as reflected by the results. Average z-scores

at the HFP

of children aged 0 - 12 months for November 1996, 1997 and1998, revealed height-for-age of –1.2 SD, –0.8 SD, and –1.1 SD

The PEM scheme register revealed that the HFP could not

and weight-for-age of –0.4 SD, –0.3 SD, and –0.1 SD. Weight-

successfully detect, target and monitor nutritionally at-risk

for-age z-scores deteriorated further after 18 months, while

preschool children. More than 40% of preschool children with

height-for-age z-scores for preschool children older than 12

growth faltering were not detected and targeted for food

months remained the same. Average height- and weight-for-

supplementation before referral from the CBGM system. The

age z-scores remained consistently below the reference median.

number of children who received less than four food

Annual low birth weight prevalence rates varied between 17%

supplements in 12 months at intervals varying from 2 to 10

and 22%. Stunting prevalence rates among the preschool

months, reflected a failure rate of 87.5%. Failure of 62.5% of the

population varied between 14% and 15%, underweight 5 - 7%,

mothers to return for follow up reflect the low priority of the

and wasting 0.5 - 1%.

PEM scheme programme at the HFP.

Despite well-planned nutrition strategies, the prevalence of

low birth weight remains high (20%), and exclusive breast-feeding practices and iron deficiency among preschool children

Impact of the HFP on nutrition and health care

in Langebaan remain a problem.7,8,13,19,20 Iron requirements for

The prevailing low preschool attendance and low priority

low-birth-weight infants (less than 2.5 kg) or infants born

given to preventive health care should not be allowed as they

before 37 weeks are increased, and iron supplementation from

influence health practices negatively. The CBGM system using

the age of 6 weeks is therefore recommended.21 Guidelines to

women from the community has strengthened preventive

support these recommendations and criteria that are effective

health practices and should therefore not be seen as an

in targeting high-risk pregnant mothers for food and/or iron

obstacle, but rather as a mechanism to improve comprehensive

supplementation need to be communicated clearly for effective

health care delivery. The increased prevalence of tuberculosis

implementation of nutrition programmes at the HFPs.7,8,13,20,22

and HIV infection limits the capacity of nursing staff at the

Nutrition programmes at the HFPs which include the PEM

HFP, which signals a need for such models to enhance social

scheme, have functioned poorly during the past decade and are

130 development, improve nutrition and health care delivery and

largely attributed to poor GM and promotion and sporadic

reduce disease recurrence.3, 8,13,14

preschool coverage for GM.6,7,8,13,20 The HFPs can potentiallyreach all preschool parents during their infants' first 9 months

Sporadic preschool attendance at the HFP

of life to promote nutrition and health through accurate GM as

Nursing staff emphasising curative care and the mothers'

this is part of routine health practice. Despite this, GM and

wrong perceptions of the HFPs contribute largely to sporadic

nutrition practices remain unsatisfactory.23,24 Berg's questioningof operational nutritionists and academics for golden

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4 SAJCN

opportunities lost, misdirected efforts, and ignoring local needs

Briend and Bari25 believe that mothers who recognise

and preferences, is therefore justified.24

abnormal growth might be prompted to take action to preventtheir child's death. The positive effect of the CBGM system in

The ZOPP workshop and impact of the CBGM

growth promotion, as measured by the increased number of

model on nutrition and health care

mothers who reported for GM, is encouraging.

The ZOPP workshop demonstrated that attitudes such as

Advantages of the CBGM model

health professionals claiming the monopoly on healthknowledge and management could be eliminated through

The CBGM model is not a blueprint, but can be recommended

acknowledgement, involvement and joint commitment by

for alleviating shortcomings of HFPs in urban areas. It has the

health professionals, the community and stakeholders in

capacity for large-scale implementation, monitoring, follow-up

programme planning from the initial stage.14 Alternative

and evaluation of programmes on a sustained basis, viz.

solutions for priority needs identified could be debated and

nutrition surveillance, and vitamin A, iron and food

accepted collectively. The NIRU staff of the MRC facilitated the

supplementation. It provides accurate and representative data

establishment of the CBGM system, while the community

on nutritional status and ensures comprehensive detection and

committed itself to addressing priority needs and providing

targeting of high-risk groups for intervention. The cost of

venues to serve as additional health stations for GM and

appointing three women on a part-time basis three times a year

important interventions. Training of women to drive the

varied from R8 000 to R10 000 (10 days), while exposure to

process facilitated transfer of knowledge and skills to the

medico-legal risks or impingement on physical resources was

community; this allowed inadequacies related to GM, health

and nutrition surveillance to be addressed, and facilitated 4-

Although proposals for iron supplementation, screening, and

monthly deworming of children 2 years and older. This

free deworming at HFPs have not yet been implemented either

complemented the HFP in preventive care delivery.

regionally or nationally, the model has successfully facilitated

Although three women could comfortably operate the

screening and management of iron deficiency and mass

CBGM system, training an additional eight ensured continuity

deworming.20,26,27 Mass deworming was found to be of

and future benefits to the community. The sustained CBGM

immediate benefit in high-risk populations for the effective

contributed to the achievement of national health objectives as

prevention of worm infections and the harmful effects of

it encompasses the principle of community participation, an

Trichuris-dysentery syndrome on growth in children.27-30

essential element for the transformation of health services in

Overcrowding, poverty and malnutrition that precipitate

South Africa.8 In this way, the model demonstrated that the

disease are often obscured in well-serviced urban areas with

perceptions of passive recipients of health care could be

the requisite health facilities. Enlisting complementary systems

such as the CBGM model could potentially reduce theepidemic proportions of tuberculosis and HIV infections and

The CBGM model and GM practices

the high prevalence of low birth weight in disadvantaged

The HFP survey ran concurrently with the CBGM model for

urban communities.

the last 5 months of the year and demonstrated differences inGM practices and preschool child coverage for GM between

the two systems before and after establishment of the model.

The 4-monthly GM improved the average coverage of

Considering the results of studies done in Alexandra, the

preschool children by more than 60%. It also improved the

Eastern Cape, Eersterust and KwaZulu-Natal, one would

detection and targeting of nutritionally at-risk and

assume that the situation in Langebaan is not unique, but could

malnourished preschool children by more than 40%.

be indicative of a countrywide situation. The 3-year evaluationof the CBGM model in Langebaan has demonstrated that

This system improved health and nutrition surveillance of

shortcomings in terms of health and nutrition surveillance

the preschool population and indicated that infants were

could be eliminated and the HFP could be complemented with

nutritionally compromised before their birth as reflected by the

guidance and minimal supervision. This is necessary for

high prevalence rate of low birth weight, and mean height-for-

improving the quality of health care of South Africans in

age z-scores below the reference median from birth. It is

believed that stunting reflects serious problems associated withpoor environmental and socioeconomic factors, repeated

The authors acknowledge co-workers Ms Vera Arendse, Mrs

exposure to adverse conditions and chronic malnutrition in

Deirdré Sickle, Mrs Karen Koegelenberg and Miss Lesleen Adonis;

populations. Height assessment, which is neglected, should

statisticians Mrs J A Laubscher and Dr C Lombard; technical

therefore receive more priority. 2,11

support Mr De Wet Marais, Mrs Martelle Marais, Ms Johanna VanWyk, Mr Eldrich Harmse, Ms E Strydom and Mrs A Potgieter; and

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4 SAJCN

Langebaan nutrition monitors Mrs Joan Blake, Mrs Jeremien

12. Jeliffe DB, Jeliffe EFP. Community Assessment with Special Reference to Less Technically Developed

Countries. Oxford University Press,1989.

Blaauw, Mrs Donitha Cupido, Ms Gertrude Engelbrecht, Ms

13. South African Health Review. Durban: Health Systems Trust and Henry J Kaizer Foundation,

Denelda Ocks, Mrs Eileen Ocks, Mrs Rhona Ocks, Mrs Wilna

1996: 141-150.

Pholman, Mrs Doreen Tango and Mrs Daphne Van Der

14. De Villiers MR, De Villiers PJT. Lessons from an academic comprehensive primary health

care centre. S Afr Med J 1996; 86: 1385-1386.

15. Gerein NM, Ross DA. Is growth monitoring worthwhile? An evaluation of its use in three

child health programmes in Zaire. Soc Sci Med 1991; 32: 667-675.

Financial support was received from Sanlam Insurance

16. Kuhn L, Zwarenstein M. Weight information on the ‘Road to Health' card inadequate for

Company and the South African Sugar Association. Special

growth monitoring. S Afr Med J 1990; 78: 495-496.

acknowledgements go to Mr Andy Evans for his sacrifice,

17. World Health Organisation. Guidelines for Training Community Health Workers in Nutrition. 2nd

ed. Geneva: WHO, 1986.

enthusiasm and dedication to the project and the people of

18. Thaver IH, Midhet F, Hussain R. The value of intermittent growth monitoring in Primary

Langebaan and to Dr Henk Tichelaar as independent reviewer.

Health Care Programmes. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 1993; 43: 129-133.

Dietary Practices and Iron Status of Preschool Children in Langebaan (Report to Sugar

Association). Parrowvallei: Medical Research Council, 1998; 1-28.

20. South African Vitamin A Consultative Group (SAVACG). Anthropometric, vitamin A, iron

and immunisation coverage status in children 6 - 71 months in South Africa 1994. S Afr Med

1. Chopra M, Sanders D. Growth monitoring — is it a task worth doing in South Africa? S Afr

J 1996; 86: 354-356.

Med J 1997; 87: 875-877.

21. Ireland JD, Power DJ, Woods DL. Primary Care for Paediatric Clinical Nurses. Cape Town:

2. Coetzee DJ, Ferrinho P. Nutritional status of children in Alexandra Township. S Afr Med J

University of Cape Town Press, 1981: 63-67.

1994; 84: 413-415.

22. Dhansay MA, Schoeman SE, Dixon M, Kunneke E, Laubscher JA, Benadé AJS. Risk markers

3. Tarin EU, Thunhurst C. Community participation with provider collaboration. World Health

for low birth weight in women attending an antenatal clinic in Bishop Lavis, a low socio-

Forum 1998;

economic area (abstract). S Afr J Food Sci Nutr 1996; 8: Suppl, 14.

19: 72-75.

4. Yach D, Martin G, Jacobs M, eds Towards a National GOBI-FFF Programme for South Africa

23. Fry J, Hassler J, eds. Primary Health Care 2000. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1986:

(Proceedings of the Health Seminar, Cape Town). Parowvallei: Medical Research Council,

Chapters 6, 10.

24. Berg A. Sliding toward nutrition malpractice: time to reconsider and redeploy. Am J Clin Nutr

5. Harrison D, Heese de V, Harker H, Mann MD. An assessment of the ‘Road to Health Card'

1992; 57: 3-7.

based on perceptions of clinic staff and mothers. S Afr Med J 1998; 88: 1424-1428.

25. Briend A, Bari A. Critical assessment of the use of growth monitoring for identifying high

6. Kuhn L, Zwarenstein MF, Katzenelenbogen J. Village health-workers and GOBI-FFF:

risk children in PHC programmes. BMJ 1989; 298: 1607-1611.

evaluation of a rural programme. S Afr Med J 1990; 77: 471-475.

26. Dhansay MA, Sickle DM, Van Stuijvenberg ME, Fincham JE, Schoeman SE, Benadé AJS. Iron

7. Department of Health. Protein Energy Malnutrition Scheme. Western Cape Provincial Update,

deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in infants, toddlers, school children in the Western

Circular No. 68 of 1996. Provincial Administration, Western Cape.

Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. XVth Meeting of the International Society of Haematology —Africa and European division, Durban, 18-23 Sep 1999: 64.

8. White Paper for the transformation of the health system in South Africa. Government Gazette

382 (17910); 1997: 26-46.

27. Fincham JE, Evans AC, Dhansay MA, Yach D, Schoeman SE. The Case for Mass Deworming.

Durban: Health Systems Trust Update, 1996: 20.

9. Faber M, Oelofse A, Benade AJS. A model for a community-based growth monitoring

system. Afr J Health Sci 1998;

28. Callender JE, Walker SP, Grantham-McGregor SM, Cooper ES. Growth and development four

5: 72-78.

years after treatment for the trichuris dysentery syndrome. Acta Paediatr 1998; 87: 1247-1249.

10. Oelofse A, Muslimuslimatun S, Schultink W. The Ziel Orientierte Projekt Planung (ZOPP)

Procedure. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000;

29. Savioli L. Treatment of trichuris infection with Albendazole. Lancet 1999; 353: 237-238.

13: 40-43.

11. Gorstein J, Sullivan K, Yip R, et al. Issues in the assessment of nutritional status using

30. Winstanley P. Albendazole for mass treatment of asymptomatic trichuris infections. Lancet

anthropometry. Bull World Health Organ 1994;

1998; 352: 1080-1081.

72: 273-283.

Nov./Dec. 2003, Vol. 16, No. 4 SAJCN

CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY FOR DIETITIANS

SAJCN CPD activity No 23 – December 2003

You can obtain 3 CPD points for reading the article: "A community-based growth monitoring model to complement facility-based

nutrition and health practices in a semi-urban community in South Africa" and answering the accompanying questions.

This article has been accredited for CPD points for dietitians. (Ref number: DT 04/3/002/12)

HOW TO EARN YOUR CPD POINTS

1. Check your name and HPCSA number.

2. Read the article and answer all the questions.

3. Indicate your answers to the questions by coloring the appropriate block(s) in the cut-out section at the end of this questionnaire.

4. You will earn 3 CPD points if you answer more than 75% of the questions correctly. If you score between 60-75% 2 points will be

allocated. A score of less than 60% will not earn you any CPD points.

5. Make a photocopy for your own records in case your form is lost in the mail.

6. Send the cut-out answer form by mail, NOT BY FAX to: SASPEN Secretariat, SAJCN CPD activity No 23, c/o Department of Human

Nutrition, PO Box 19063, Tygerberg, 7505 to reach the office not later than 5 March 2004. Answer sheets received after this date will

not be processed.

PLEASE ANSWER ALL THE QUESTIONS

(There is only ONE correct answer per question.)

1. The community-based growth monitoring (CBGM) system

After completion of the immunising schedule, most mothers visit

reached 70-100% of preschool children for growth monitoring

the health facility:

for weighing of the child

because the child is sick

Mothers associated a downward growth curve with a problem or

Preschool children's clinic attendance increase after the age of

a child being sick.

Most mothers understand the concept of growth monitoring.

The community-based growth monitoring (CBGM) system

increased preschool coverage by more than 60%.

10. What percentage of children received food supplements for 3

consecutive months?

Underweight tends to peak:

11. The community-based growth monitoring (CBGM) system

The recumbent position is used to measure:

replaced existing growth monitoring (GM) practices:

children under 2-years-old

children up to 6-months-old

children over 2-years-old

12. What activity was successfully facilitated through the

Which of the following was used as risk criteria in the

community-based growth monitoring (CBGM) system?

community-based system?

treatment of tuberculosis

weight-for-age < 97th percentile

weight-for-age > 3rd percentile

weight-for-age < 3rd percentile

✁ Cut along the dotted lines and send to: SASPEN Secretariat, SAJCN CPD activity No 23, c/o Department of Human Nutrition,

PO Box 19063, Tygerberg, 7505 to reach the office not later than 5 March 2004

HPCSA number: DT

Surname as registered with HPCSA: Initials:

Postal address: _

Full member of ADSA: yes no If yes, which branch do you belong to?

134 Full member of SASPEN: yes no Full member of NSSA: yes no

"A community-based growth monitoring model to complement facility-based nutrition and health practices in a semi-urban

community in South Africa"

SE Schoeman, MA Dhansay, JE Fincham, E Kunneke, AJS Benadé

Please color the appropriate block for each question

(e.g. if the answer to question 1 is a: 1) a b)

Source: http://sajcn.co.za/index.php/SAJCN/article/viewFile/43/39

Antiviral Research 71 (2006) 154–163 Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases Department of Clinical Virology, Division of Virology, GlaxoSmithKline Inc., RTP, NC, United States Received 15 March 2006; accepted 4 May 2006 Dedicated to Prof. Erik De Clercq on the occasion of reaching the status of Emeritus-Professor at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in September 2006

Design of the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) Protocol 054: A cluster randomized crossover trial to evaluate combined access to Nevirapine in developing countriesJim HughesUniversity of Washington, [email protected] Robert L. GoldenbergUniversity of Alabama, [email protected] Catherine M. WilfertElizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation/Duke University, [email protected]