Microsoft word - titelblad_x.doc

From the Department of Orthopaedics,

Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Sweden

The infected knee arthroplasty

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Anna Stefánsdóttir

List of papers, 2

Results / Summary of papers, 20

Definitions and abbreviations, 3

Introduction, 4

Historical background, 4

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, 4

Definition of infected knee arthroplasty, 4

Discussion, 25

The size of the problem, 5

Limitations of the study, 25

Classification, 6

Timing and type of infection, 25

Infecting microorganisms, 7

Antibiotic susceptibility, 26

Type of treatment, 27

The results of treatment, 27

Effects on quality of life, 11

Prognostic factors for failure to eradicate infec-

Economic impact, 12

Antibiotic prophylaxis, 12

Timing of antibiotics, 28

Other prophylactic measures, 13

Conclusions, 30

Aims of the study, 14

Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning, 31

Patients and methods, 15

Yfirlit á íslensku, 32

Papers I–III, 15

References, 34

Original papers I–IV

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

The thesis is based on the following papers:

I. Stefánsdóttir A, Knutson K, Lidgren L, and III. Stefánsdóttir A, Knutson K, Lidgren L, and

Robertsson O. The time and type of deep

Robertsson O. 478 primary knee arthroplasties

infection after primary knee arthroplasty.

revised due to infection – a nationwide report.

II. Stefánsdóttir A, Johansson D, Knutson K, IV. Stefánsdóttir A, Robertsson O, W-Dahl A,

Lidgren L, and Robertsson O. Microbiology

Kiernan S, Gustafson P, and Lidgren L. Inad-

of the infected knee arthroplasty: Report from

equate timing of prophylactic antibiotics in

the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register on

orthopedic surgery. We can do better.

426 surgically revised cases.

Acta Orthopaedica 2009; 80(6): 633-8.

Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases

2009; 41(11-12): 831-40.

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Definitions and abbreviations

Biofilm Organised communities of aggregated

PMMA Poly(methyl methacrylate): bone cement

bacteria embedded in a hydrated matrix of extracellular polymeric substances

Primary arthroplasty

The first time one or more joint sur-

Coagulase-negative staphylococci

faces are resurfaced with prosthetic implant(s)

Colony-forming unit. A measure of

the number of viable bacteria. In air

RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

expressed as cfu/m3

Revision arthroplasty

Cumulative revision rate

A reoperation during which prosthetic component(s) are either exchanged,

Index operation

removed, or added

First-time revision, due to an infection

Minimum inhibitory concentration: the lowest concentration of an antimi-

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Regis-

crobial substance that will inhibit the

visible growth of a microorganism after overnight incubation

Surgical site infection

Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus TKA

Tricompartmental knee arthroplasty

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty

Polymerase chain reaction: a tech-nique for in vitro amplification of spe-cific DNA sequences from organisms, including bacteria.

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

tion after a primary knee arthroplasty that involves

addition, exchange, or removal of at least one

The development of modern knee arthroplasty prosthetic component (including arthrodesis and started in the 1940s. In 1953 Walldius, an ortho-

amputation). The reason for revision is recorded

paedic surgeon in Stockholm, described promis-

based on a report from the operating surgeon and

ing results with the use of a hinge prosthesis made information retrieved from hospital records. In a

of acrylate (Walldius 1953). Even though aseptic validity study, it was estimated that 94% of revi-

and antiseptic techniques were well implemented sions were accounted for (Robertsson et al. 1999).

at this time, infection was a significant problem.

In his series of 32 arthroplasties, performed on 26

patients, Walldius reported fatal septicaemia in 1

Definition of infected knee arthroplasty

case, amputation due to infection in 2 cases, and arthrodesis due to infection in 4 cases (Walldius No standardised criteria of infected knee arthro-1957). Sir John Charnley, the great pioneer in hip plasty are available. The finding of a microor-arthroplasty, addressed the infection problem by ganism in cultures from tissue biopsies has been developing an operating theatre with ultra-clean referred to as the gold standard (Banit et al. 2002), air and a body exhaust system. By these measures, but some authors have instead used histological the infection rate after hip arthroplasty was brought criteria of infection (Atkins et al. 1998). It is well down from more than 7% to 0.6% (Charnley 1979). known that in some cases of infected knee arthro-In the early 1970s the principles of low-friction plasty, culture fails to reveal any microorganism – arthroplasty were applied to the knee joint (Insall and the possibility of false-positive cultures must et al. 1976), and with continuing development knee also be considered. In clinical practice, the diag-arthroplasty has become a routine operation that is nosis of infection is made by sound interpretation performed on a large scale throughout the industr-

of medical history, clinical signs, laboratory tests,

diagnostic imaging, microbiology, and macro-scopic findings during surgery.

A clear distinction has to be made between a

superficial infection and an infection located within

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register

the joint capsule, involving the prosthetic implant.

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) An anatomy-based nomenclature scheme of noso-was established in 1975 by the Swedish Ortho-

comial surgical site infections (SSIs) was presented

paedic Society, and it was the first national arthro-

by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in 1992

plasty register. The main aims were to give early (Horan et al. 1992), and this is now widely used warning of inferior designs and to present aver-

for surveillance (Morgan et al. 2005, Barnes et al.

age results based on the experience of a whole 2006). According to this scheme, SSIs are divided nation instead of that of highly specialised units into incisional SSIs and organ/space SSIs. Inci- (Robertsson et al. 2000b). Currently there are 76 sional SSIs are further classified as involving only orthopaedics departments in Sweden that perform the skin and subcutaneous tissue (superficial inci-knee arthroplasties, and all report to the register. sional SSIs) or involving deep soft tissues (i.e. fas-In September 2010, the database contained infor-

cial and muscle layers) of the incision (deep inci-

mation on 165,000 primary knee arthroplasties and sional SSIs). To be classified as an organ/space SSI, 12,450 revision knee arthroplasties. The main out-

the infection has to occur within 1 year of implanta-

come variable reported by the register is revision tion and it should appear to be related to the pro-arthroplasty, which is defined as any later opera-

cedure (Horan et al. 1992). In the case of infected

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Yearly number of knee arthroplasties

n = 12,129

n = 20,349

n = 34,224

n = 28,441

ight 2010 SKARyr

ight 2010 SKARyr

Year of operation

Year after index operation

Figure 1. The annual number of arthroplasties for dif-

Figure 2. The CRR because of infection in OA patients

ferent diagnoses registered in the SKAR. From the

undergoing primary TKA during different time periods.

SKAR Annual report 2010, available at www.knee.se.

From the SKAR Annual report 2010, available at www.

knee.se.

knee arthroplasty this nomenclature is confusing, 5 years (Furnes et al. 2002). In Finland data from as the largest part of the incision does not involve the Finnish Hospital Infection Program, the Finn-any muscle layer. In practice, there will be two ish Arthroplasty Register, and the Finnish Patient classes: (1) superficial incisional SSI (involving Insurance Center were cross-matched and the skin and subcutaneous tissue), and (2) organ/space infection rate for 5,921 cases of TKA performed SSI (involving the joint, with the joint capsule as a during 1999–2004 was estimated to be 1.3% (Huo-natural boundary). In this work the organ/space SSI tari et al. 2010). In the USA, the risk of infection is termed infected knee arthroplasty.

after TKA was reported to be 1.55% within 2 years in 69,663 patients in the Medicare population, the infections being identified by ICD-9 codes (Kurtz et al. 2010). In that study, patients undergoing

The size of the problem

TKA because of a bone cancer, a fracture, or joint

Despite the large number of operations performed infection were excluded, as were patients younger each year, it is difficult to obtain reliable informa-

tion on the incidence of infected knee arthroplasty.

With the increasing number of primary knee

The national arthroplasty registers provide some arthroplasties (Figure 1), the number of infected information, but it must be remembered that there cases will increase. It has been predicted that can be methodological differences between reg-

infection will become the most frequent mode of

isters. Of the 34,701 primary knee arthroplasties failure of total knee arthroplasty, with great eco-(both total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicom-

nomic consequences (Kurtz et al. 2007). In Den-

partmental knee arthroplasty (UKA)) reported to mark in 2008, infection was reported to be the the SKAR during 1999–2003, 0.65% were revised most common reason for revision (32.1%) (DKR due to infection within 5 years. 29,928 were pri-

2009), and in Australia in 17.1% of cases (AOAN-

mary TKAs and 0.70% of them were revised JRR 2009). In Sweden and in England, in 2009, because of infection within 5 years (personal infection was reported to be the cause of revision in information from the SKAR, September 2010). 23% of cases (NJR 2010, SKAR 2010).

Of 6,133 cemented TKAs reported to the Nor-

Data from the SKAR has been used to calculate

wegian arthroplasty register during 1994–2000, the cumulative revision rate (CRR) due to infection 0.44% were revised because of infection within in OA patients undergoing TKA (Figure 2). The

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

CRR due to infection decreased during the first time periods studied, but there was a slight increase in CRR in patients operated during the years 2006–2008, compared to those operated during the years 2001–2005.

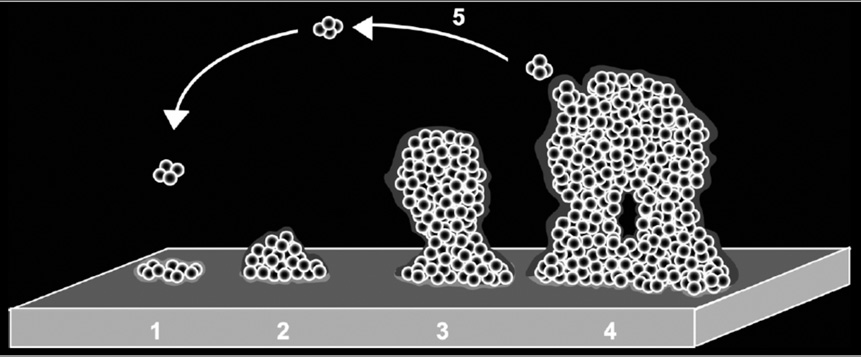

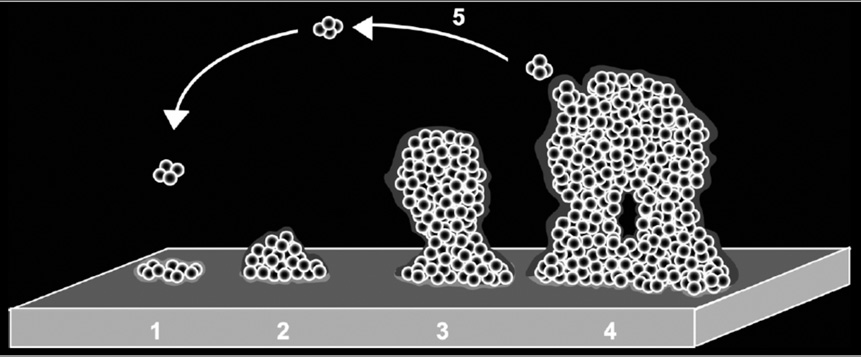

Figure 3. The development of a biofilm, depicted as a five-stage process. Stage 1: initial attachment of cells to

There is no consensus on a classification system

the surface; stage 2: production of extracellular poly-

for infected arthroplasties.

meric substances; stage 3: early development of biofilm architecture; stage 4: maturation of biofilm architec-

Zimmerli and co-workers have suggested that

ture; stage 5: dispersion of bacterial cells from the bio-

prosthetic joint infections should be classified

film. From: Lasa I. International Microbiology 2006; 9:

as three types: early, delayed, and late infections

21–28. Published with permission.

depending on the time of appearance of the first

signs and symptoms of infection (Zimmerli and (chronic) infections. This classification has been

Ochsner 2003). According to this scheme, early used in a staging system that has been shown to be

infections present during the first 3 months after predictive of outcome when treating infected knee

surgery, delayed infections present between 3 arthroplasties (McPherson et al. 1999, Cierny and

months and 2 years, and late infections present 2 DiPasquale 2002).

years or more after the arthroplasty. The late infec-

tions may appear either with a sudden systemic

inflammatory response syndrome or without initial Pathogenesis

signs of sepsis, with a delayed course after a clini-cally unrecognised bacteraemia. This classification How do bacteria aggregate in a biofilm and how do scheme highlights the pathogenesis and the pre-

they live in it? The answers to these questions are

sumed fact that most infections diagnosed within central to our understanding of the pathogenesis 2 years after primary arthroplasty are acquired of infected knee arthroplasty. A biofilm is defined during the perioperative period.

as an organised community of aggregated bacte-

A classification system meant to be of assistance ria embedded in a hydrated matrix of extracellular

when selecting treatment was presented by Segawa polymeric substances (Hall-Stoodley and Stoodley and co-workers (Segawa et al. 1999), who defined 2009). Biofilms can be formed by most, if not all, an early postoperative infection as a wound infec-

microorganisms and today the biofilm mode of life

tion (superficial or deep) that develops less than is regarded as the rule rather than the exception four weeks after the index operation. They defined (Jefferson 2004, Lewis 2007, Coenye and Nelis a late chronic infection as one that develops four 2010).

weeks or more after the index operation and has

Biofilm formation is a multi-stage process (von

an insidious clinical presentation. They defined an Eiff et al. 2002) that starts with attachment of bac-acute haematogenous infection as one that is asso-

teria to the implant surface. At the same time, the

ciated with a documented or suspected anteced-

implant is coated with proteins from the host, with

ent bactaeremia and that is characterised by acute which the bacteria can attach by specific surface onset of symptoms. In addition, they defined a sep-

proteins. The next step is proliferation and accu-

arate group of infections: those that are clinically mulation in multi-layered cell clusters, which are inapparent but where there are at least 2 positive embedded in extracellular polymeric substances cultures from specimens obtained at the time of a (containing polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA). presumed aseptic revision (Segawa et al. 1999). An As the biofilm matures, focal areas may dissolve attempt at debridement with salvage of the pros-

and the liberated bacterial cells can spread to

thesis was recommended in early postoperative another location where new biofilms can be formed infections, and removal of the prosthesis in late (Lasa 2006, Hoiby et al. 2010) (Figure 3). Bacte-

Anna Stefánsdóttir

had on the rate of infection emphasises the impor-tance of intra-operative contamination (Lidwell et al. 1987).

Bacteria are responsible for the vast majority of knee arthroplasty infections, with occasional infec-

Figure 4. Model of biofilm resistance. An initial treat-

tions caused by fungi – most commonly a member

ment with antibiotic kills planktonic bacterial cells

of the genus Candida (Hennessy 1996). The bacte-

and the majority of bacterial cells in the biofilm. The immune system kills planktonic persisters but the bio-

ria most commonly found in infected knee arthro-

film persister cells are protected from the host defenses

plasties are Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and

by the exoplysaccharide matrix. After the antibiotic

coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS), of which

concentration drops, persisters resurrect the biofilm and the infection relapses. From: Lewis. Antimicrobial

Staphylococcus epidermidis in this context is the

Agents and Chemotherapy 2001; 45(4): 999–1007. Pub-

most important species.

lished with permission.

It has been stated that early infections are caused

by virulent microorganisms such as S. aureus and

rial cells embedded in the biofilm communicate Gram-negative bacteria, whereas delayed (low-with each other and show a coordinated group grade) infections are caused by less virulent micro-behaviour mediated by a process called quorum organisms such as CNS and Propionibacterium sensing (Coenye and Nelis 2010).

acnes (Kamme et al. 1974, Zimmerli et al. 2004).

The extracellular polymeric substances protect

the bacteria from the host's immune cells and

restrict the diffusion of antimicrobials into the Risk factors

biofilm. Bacteria in the deeper layers of a thick biofilm have less access to nutrients and will grow Men have a higher risk of revision because of more slowly, which reduces the effect of antibi-

infection than women (Figure 5a) (Robertsson et

otics active against proliferating bacteria. A sub-

al. 2001, Furnes et al. 2002, Jämsen et al. 2009a),

population of the bacteria in the biofilm is named but the reason for this is unknown.

persisters, which are bacteria that are highly toler-

Rheumatoid patients have a higher risk of revi-

ant to antibiotics – even those active against slowly sion because of infection than OA patients (Figure growing bacteria – and when the antibiotic concen-

5b) (Robertsson et al. 2001, Schrama et al. 2010).

tration drops, the persisters resurrect the biofilm The reason for this may be related to the disease and there is relapse of infection (Figure 4) (Lewis and to the anti-rheumatic treatment. Glucocorti-2001, Lewis 2007).

coid agents are known to increase the risk of infec-

To start biofilm formation, bacteria must have tion (Bernatsky et al. 2007) whereas the effect of

access to the joint and there are several possible the new biological anti-rheumatic drugs on the routes of entry. Bacteria, either from the patient's incidence of infection following orthopaedic sur-skin or from the surroundings, can contaminate the gery has not been clarified (Giles et al. 2006, den joint at the time of surgery. Bacteria can also gain Broeder et al. 2007). access to the joint from an adjacent infection, either

Primary UKAs have a lower risk of revision

a postoperative superficial SSI or a later abscess because of infection than TKA (Figure 5c). around the knee joint. They can spread haematog-

Obesity is a growing problem in many parts of

enously from a distant focus, and finally, they can the world, and at least in the USA the mean BMI spread as an iatrogenic infection in conjunction of patients undergoing knee arthroplasty is rising with arthrocentesis, arthroscopy, or surgical inter-

(Fehring et al. 2007). In a study in which more

vention in the joint. The effect that the introduction than half of the patients had a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/of ultra-clean air and prophylactic antibiotics has m2, obesity was a risk factor for infection (Namba

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

n = 27,435

n = 43,742

ight 2010 SKAR

ight 2010 SKAR

ight 2010 SKAR

Year after index operation

Year after index operation

Year after index operation

Figure 5. Using the endpoint "revision for infection", the CRR (1999–2008) shows in TKA for OA that men are more affected than women (RR = 2.0). The same tendency is true for RA, although not statistically significant. UKA with its smaller implant size does better than the larger TKA, but even in UKA men have 2.9 times the risk of women of becoming revised for infection. In TKA, patients with RA are more affected than those with OA (RR = 1.7). From the SKAR Annual report 2010, available at www.knee.se.

et al. 2005). Obese patients often have other co-morbidities such as diabetes, which increases the risk of infection (Dowsey and Choong 2009). Pre-operative hyperglycaemia has recently been shown to be predictive of infection after a primary knee arthroplasty (Jämsen et al. 2010).

Smoking may increase the risk of SSI (Mangram

et al. 1999). In an interventional study, wound-related complications were found to be less fre-quent in the group of patients who had smoking intervention 6–8 weeks before scheduled hip or knee arthroplasty (Møller et al. 2002).

The risk of infection is increased in revision sur-

gery, when constrained or hinged prostheses are used, and when there is a history of earlier fracture in the joint (Jämsen et al. 2009a).

Figure 6. A 59-year-old man with OA attended hospi-

Post-operative wound complications are a strong tal with fever (38°C) and a painful knee 14 days after

predictor of later diagnosis of infected arthro-

undergoing primary knee arthroplasty. Open debride-

plasty (Wymenga et al. 1992b, Berbari et al. 1998, ment was performed, and methicillin sensitive S. aureus

was cultured from 5 out of 5 tissue biopsies. Antibiotic

Jämsen et al. 2009a). It appears likely that many of treatment started with i.v. cloxacillin, followed by p.o. these presumed superficial SSIs and wound com-

ciprofloxacin and rifampicin. The infection could be

plications were actually deep infections.

eradicated and the implant retained. Published with permission from Bertil Christenson.

the degree of suspicion. In delayed and late infec-

tions, pain and/or stiffness may be the predominant

There is a large variation in the symptoms and complaint, often in conjunction with mild to mod-signs of infected knee arthroplasty, depending on erate effusion in the joint. the type of infection, the infecting microorganism,

The laboratory tests found to be of value are

and the immunological status of the patient (Fig-

C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedi-

ures 6 and 7). The presence of – or a history of mentation rate (ESR) (Sanzén and Carlsson 1989, – post-operative wound complication should raise Parvizi et al. 2008a). There is a normal rise in CRP

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Figure 7. A 66-year-old woman with RA was treated with glucocorticoid, metho-trexate, and remicade, and on the third day after undergoing primary knee arthroplasty she received p.o. flucloxacillin due to discharge from the wound. She attended hospital at day 16 (picture) because of continued discharge. Open debridement was performed, and methicillin resistant CNS was cultured in 5 out of 5 tissue biopsies. Antibiotic treatment started with i.v. vancomycin, followed by p.o. clindamycin and rifampicin. The infection could be eradicated and the implant retained.

in conjunction with surgery, with a peak on the prosthetic joint infection were found to be 1.1 × second day (White et al. 1998), and near normali-

109/L for fluid leukocyte count and 64% for neu-

sation at the end of the second week (Niskanen et trophil differential; when combined with CRP and al. 1996). The level of synovial fluid IL-1 and IL-6 ESR, infection could safely be excluded or con-has recently been shown to differentiate patients firmed (Parvizi et al. 2008a).

with periprosthetic infection from patients with

The sensitivity of synovial fluid culture has

aseptic diagnosis (Deirmengian et al. 2010).

varied between 50% and 100% in different studies

Plain radiographs are necessary to visualise (Meermans and Haddad 2010). Blood culture bot-

the state of the implant, and to look for signs of tles are recommended (Font-Vizcarra et al. 2010), periprosthetic bone destruction and loosening. and in the case of small amounts of fluid gained, a Radionuclide imaging has been found to be help-

paediatric bottle can be used (Hughes et al. 2001).

ful when differentiating between delayed or late

In 1981, Kamme and Lindberg reported their

infection and aseptic loosening, the combined leu-

experience with culture of biopsy samples, col-

kocyte/marrow imaging being the recommended lected during revision hip arthroplasty, and rec-procedure (Love et al. 2009). The role of CT and ommended that five separate biopsy samples be MRI has been limited due to metal artefacts, but taken (Kamme and Lindberg 1981). Other authors with technological advances these techniques may have come to the same conclusion (Atkins et al. become useful (Sofka et al. 2006).

Analysis of synovial fluid is an essential part of

With the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tech-

investigation, and leukocyte differential of > 65% nique, bacteria can be identified by amplification neutrophils (or a leukocyte count of > 1.7 × 109/L) of bacterial DNA containing the 16S rRNA gene. has been found to be a sensitive and specific test Despite interesting reports during the 1990s (Mari-for the diagnosis of prosthetic knee infection in ani et al. 1996, Tunney et al. 1999), the technique patients without underlying inflammatory joint still has a limited role in diagnosing infected knee disease (Trampuz et al. 2004). In another study, the arthroplasty (De Man et al. 2009, Del Pozo and cut-off values for optimal accuracy in diagnosis of Patel 2009) .

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

Intraoperative gram staining has repeatedly been treatment failure compared to debridement within

shown to lack sensitivity and is not recommended 2 days of onset (Brandt et al. 1997). Better results (Morgan et al. 2009).

have been reported when rifampcicin (which inhib-

Histology has been considered to be the most its bacterial RNA polymerase) has been included

reliable method in diagnosing arthroplasty infec-

in the antibiotic treatment used in conjunction

tion (Atkins et al. 1998), but it is not standardised with debridment of a stable implant (Zimmerli et and the inter-observer variability is high (Zimmerli al. 1998, Berdal et al. 2005, Soriano et al. 2006, et al. 2004).

Aboltins et al. 2007), but it is still not clear for

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Sur-

how long after surgery this strategy can be used.

geons has recently published extensive guidelines In the study by Zimmerli and co-workers, the long-for the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections est duration of symptoms was 21 days whereas in of the hip and knee (AAOS 2010).

the other studies the protocol allowed inclusion of infections diagnosed within 3 months.

Revision arthroplasty can be performed in one

or two stages. In a review paper published in 2009,

Treatment

Jämsen and co-workers summarised the results

Successful treatment of infected knee arthroplasty of one- and two-stage revision arthroplasties and involves eradication of the infection along with found that the overall success rate in eradication preservation of function in a pain-free knee joint. of infection was 73–100% after one-stage revision This may be achieved by early debridement with and 82–100% after two-stage revision (Jämsen retention of the implant or revision arthroplasty et al. 2009b). Comparison of the two methods is, in one or two stages. In certain circumstances, the however, difficult due to differences in selection.

treatment is limited to limb saving, with an arthro-

Two-stage revision arthroplasty may also be per-

desis or extraction of the implant as options, and formed in different ways. Initially, the joint was under exceptional circumstances the only alterna-

left empty during the interval between stage one

tive is above-the-knee amputation. There are cases and stage two (Insall et al. 1983). Beads made of in which suppressive antibiotic treatment is used to antibiotic-loaded bone cement were then intro-maintain function in a chronically infected joint.

duced, which allowed local administration of

Algorithms have been developed to be of help antibiotics in the joint (Borden and Gearen 1987).

when choosing treatment (Zimmerli et al. 2004), With the use of a spacer block, made of antibiotic-and favourable outcome has been coupled to adher-

loaded bone cement, it was possible to preserve the

ence to the algorithm (Laffer et al. 2006).

length of the leg, prevent adhesion of the patella

Debridement involves arthrotomy, removal of all to the femur, and thereby make stage two easier to

debris and inflamed synovial membranes, if pos-

perform (Cohen et al. 1988). An articulating spacer

sible exchange of the tibial insert (which makes (Figure 8), with separate tibial and femoral com-access to the posterior part of the joint possible) ponents, probably gives better patient comfort and and lavage with a large amount of fluid. The prob-

the range of motion after stage two may become

ability of eradicating the infection is related to better (Hofmann et al. 1995, Fehring et al. 2000, the time the biofilm has had to establish itself and Jämsen et al. 2009b). mature. It is still not clear what cases it would be

Arthrodesis can be performed in one or two

reasonable to try to treat with debridement. A dura-

stages. During the time of healing, it can be fix-

tion of less than 4 weeks has been recommended ated using either external or internal fixation, an as a time limit (Schoifet and Morrey 1990, Segawa intramedullary rod being the most common type et al. 1999), whereas in other studies the limit has of internal fixation (Knutson et al. 1984, Conway been set at 2 weeks (Borden and Gearen 1987, et al. 2004). Better results, with respect to eradica-Teeny et al. 1990, Burger et al. 1991, Wasielewski tion of infection, have been reported with the use et al. 1996). It has even been reported that debride-

of external fixation (Figure 9) whereas the rate of

ment more than 2 days after the onset of symptoms healing of the arthrodesis is higher with the use of may be associated with a higher probability of an intramedullary rod (Mabry et al. 2007).

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Figure 8. A 77-year-old man with OA who had an early infection with methicillin-resis-tant CNS after a primary knee arthroplasty. Open debridement failed, and radiographs at 7 weeks after primary surgery revealed periprosthetic bone destruction (see above). He went through a two-stage revision with the use of an articulating spacer made of vancomycin- and gentamicin-loaded bone cement. During the interval between stage 1 and 2, the antibiotic treatment consisted of i.v. vancomycin, followed by p.o. line-zolid. The infection was eradicated.

Above-the-knee amputation may be the only

alternative in the case of life-threatening sepsis or uncontrollable infection. Vascular disease in con-junction with infection may also lead to amputa-tion. High mortality and poor functional result have been reported (Fedorka et al. 2010).

Suppressive antibiotic is an alternative for patients

with chronic infection caused by a micro organism that can be suppressed with oral antibiotic(s), which can be given for long time without severe adverse effects (Segreti et al. 1998).

Effects on quality of life

Figure 9. An 86 year-old-man with RA who fell and sus-tained a rupture of the patellar ligament twelve days

Surprisingly little information is available on the

after a primary knee arthroplasty. The joint became

effect that infected knee arthroplasty has on qual-

infected with 3 kinds of bacteria (S. aureus, Proteus vul-garis, and a Haemophilus species). Due to lack of a func-

ity of life. When compared with patients with

tioning extensor mechanism, arthrodesis was chosen as

uncomplicated total joint arthroplasty, patients with

treatment with double Orthofix instruments used for

infection scored significantly lower in satisfaction

external fixation. The patient died of cerebrovascular disease, before healing of the arthrodesis.

(visual analogue scale), WOMAC, AQoL, and all aspects of SF-36 other than general health and role limitations–emotional (Cahill et al. 2008). In a

Extraction, or excision arthroplasty, can be con-

study in which 26 cases that were revised because

sidered in exceptional cases but it leaves the joint of infection were compared with 92 cases that were unstable and it is not certain that infection can be revised for reasons other than infection, the objec-eradicated by extraction of the prosthesis.

tive results after septic revision were inferior to the

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

Distribution of satisfaction, percent

are in line with an earlier study from the US where

surgical treatment of the infected total knee implant

required 3–4 times the resources of the hospital

and the surgeon compared to a primary TKA, and

approximately twice the resources of a non-septic

revision arthroplasty (Hebert et al. 1996).

Apart from the direct costs related to hospitalisa-

tion, there are considerable indirect costs related to

home care, nursing facilities, and antibiotics.

Figure 10. Results from a postal survey in 1997,

The goal of antimicrobial prophylaxis is to achieve

answered by patients who had undergone primary knee arthroplasty in the period 1981–1995 (Roberts-

serum and tissue drug levels that exceed – for the

son et al. 2000a). Of the revised cases, 47% of 232

duration of the operation – the minimum inhibitory

patients who had revision for infection and 61% of

concentrations (MICs) for the organisms likely to

1,865 patients who had revision for other reasons were satisfied or very satisfied.

be encountered during the operation (Bratzler and Houck 2004).

results after aseptic revision in terms of Knee Soci-

The first study published on prophylactic anti-

ety clinical score, function score, range of motion, biotics in joint replacements came from Sweden and return to activities of daily living (Barrack et (Ericson et al. 1973). The effect of cloxacillin as al. 2000). In a study from the SKAR, 47% of those prophylactic antibiotic in hip surgery was com-revised because of infection were satisfied or very pared with a placebo, and in the treatment group satisfied, compared to 61% of those revised for there were no infections in 83 patients after 6 other reasons (Figure 10) (Robertsson et al. 2000a).

months of follow-up whereas there were 12 infec-tions in the placebo group (8 superficial and 4 deep infections) (p < 0.001). A larger study with a longer follow-up confirmed the results and showed

a lower rate of infection in the treatment group,

In the USA the costs of prosthetic joint infections even after a follow-up of more than 2 years (Carls-during the years 1997–2004 have been analysed, son et al. 1977). The effect of the first-generation based on information from the National Hospital cephalosporin cefazolin was proven in a multi-Discharge Survey. The annual adjusted diagnos-

centre study performed in France during the period

tic-related group (DRG) cost for such infection 1975–1978 (Hill et al. 1981).

increased from $195 million to $283 million during

In a comparison between beta-lactam penicillin

these years, whereas the mean DRG reimburse-

and a first-generation cephalosporin as a prophy-

ment per hospitalisation of $9,034 did not change laxis in hip arthroplasty, there was no difference (Hellmann et al. 2010).

found between the groups (Pollard et al. 1979).

In another study from the USA, based on the In this study, flucloxacillin was given intrave-

Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, the nously for 24 hours followed by oral medication average total charge for those having a primary for 14 days, whereas cephaloridine was given as knee arthroplasty without an infection was $35,320 3 intravenous doses over the first 12 hours, and whereas the average total charge for those with the authors concluded that the simplicity of the infection was $63,705 (Kurtz et al. 2008). In a 3-g cephaloridine regime was an advantage. Beta-single-centre study, also from the USA, the mean lactam penicillin and a first-generation cepha-charge for infected revision TKA was $109,805 losporin were compared in another study using the whereas the mean charges for aseptic revision TKA same dosage scheme for both types of antibiotics was $55,911 (Lavernia et al. 2006). These figures (1 g × 3) (Van Meirhaeghe et al. 1989). There was

Anna Stefánsdóttir

no significant difference in infection rate between effect of antibiotic-loaded cement has been stud-the study groups, but the groups were heterogene-

ied more thoroughly in primary hip replacement,

ous and the study lacked power.

where there has been convincing evidence of a

There is now a general consensus that the length reduced number of infections from using antibi-

of antibiotic prophylaxis should not exceed 24 otic-loaded bone cement (Engesaeter et al. 2003,

hours, but how many doses should be given has not Parvizi et al. 2008b).

been clarified. In a multi-centre study in the Neth-

erlands, a one-dose regime with the second-gen-

eration cephalosporin cefuroxime was compared Other prophylactic measures

to 3 separate doses in patients undergoing a total hip replacement, hemiarthroplasty of the hip, or In the 1960s and early 1970s antibiotics were total knee replacement (Wymenga et al. 1992a). In seen as an alternative to ultra-clean air as opera-the one-dose group, the infection rate was 0.83% tion boxes were not widely available. By combin-(11/1,324) and in the 3-dose group it was 0.45% ing ultra-clean air and antibiotics the incidence of (6/1,327), but the difference was not statistically sepsis after surgery was much less than that when significant (p = 0.17). The authors concluded that either was used alone (Lidwell et al. 1987). With a 3-dose regimen of cefuroxime was to be recom-

the low infection rates of today, it is extremely dif-

mended until further data became available.

ficult to prove (or disprove) the effect of a single

In a study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Reg-

specific change in prophylactic measures by meas-

ister, it was shown that the risk of revision for any uring infection rate. In the operating theatre, cfu/reason was higher when one dose of antibiotic (as m3 is used as a measure of the quality of the air, compared to 4 doses) was given within 24 hours, and this value should be less than 10. whereas there was no significant difference in the

A shower with chlorhexidine solution has been

risk of revision between administration of 3 and shown to effectively decrease bacterial counts on 4 doses within 24 hours. When the endpoint was the skin (Byrne et al. 1991), and in Sweden at revision due to infection, no statistically significant least two preoperative chlorhexidine showers are difference was found (Engesaeter et al. 2003).

routine before knee arthroplasty surgery. It has,

The timing of the pre-operative antibiotic proph-

however, not been proven that this routine reduces

ylaxis is important (van Kasteren et al. 2007), the number of infections. In a recent study, pre-especially when a tourniquet is used (Tomita and operative screening to identify nasal carriers of S. Motokawa 2007).

aureus and subsequent treatment with nasal mupi-

The risk of haematogenous infection in conjunc-

rocin and chlorhexidine soap reduced the number

tion with dental procedures has been debated, but of infections (Bode et al. 2010). Other studies have it is now clearly understood that antibiotic prophy-

shown that in people who are nasal carriers of S.

laxis is not needed for all patients with total joint aureus, the use of mupirocin ointment results in a replacement prior to dental procedure (Berbari et statistically significant reduction in S. aureus infec-al. 2010, Zimmerli and Sendi 2010).

tions (van Rijen et al. 2008), but possible resist-ance to mupirocin has to be monitored (Caffrey et al. 2010).

Other prophylactic measures include optimisa-

Bone cement

tion of the patient's condition prior to operation,

The Australian arthroplasty register reported a minimising the length of stay at the hospital prior lower rate of revision due to infection when anti-

to operation, and strict addiction to hygiene rou-

biotic cement was used (0.67%) than when plain tines.

cement was used (0.91%) (AOANJRR 2009). The

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

Aims of the study

The aims of the study were:

1. to determine the timing and type of deep infec-

4. to evaluate the results of surgical treatment of

tion after a primary knee arthroplasty, and to

infected knee arthroplasty, and identify possi-

evaluate the most commonly used classifica-

ble factors that may be predictive of the out-

2. to determine the microbiology of surgically 5. to study the timing of administration of the first

revised infected primary knee arthroplasty

dose of prophylactic antibiotics in orthopaedic

and the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of the

pathogens isolated;

3. to determine what type of surgical treatment

Swedish orthopedic surgeons have used for infected knee arthroplasty;

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Patients and methods

primary knee arthroplasties

revised due to infection

281 knees/279 patients

Paper I and III

197 knees/193 patients

n = 478 (472 patients)

mean age at primary op. 68 (14–88)mean age at index op.

244 knees/242 patients

182 knees/179 patients

n = 426 (421 patients)

mean age at primary op. 68 (14–88)mean age at index op.

176 knees/patients

115 knees/patients

mean age at primary op. 70 (43–90)

74 operations/patients

40 operations/patients

mean age at primary op. 77 (26–96)

Figure 11. An overview of patient allocation.

and the results of treatment was gathered retro-

spectively from patient records, operation reports,

Patients who were included. Patients who had and culture reports which were requested from the

their primary knee arthroplasty revised for the involved orthopaedics departments and microbiol-

first time during the years 1986–2000, due to deep ogy laboratories involved.

infection, were included in the studies. No criteria

Patients who were excluded. Of the 526 revi-

had to be fulfilled other than that the treating sur-

sions, 48 knees (9.1%) were excluded. In 22 cases,

geon had diagnosed the knee as being infected at the operating surgeon at the time of surgery sus-the time of revision. This first revision was defined pected infection and, based on this report, the as the index operation. In December, 2003, the reason for revision was registered to be infection. SKAR was searched for cases fulfilling this crite-

A review of the medical records showed that infec-

rion and 526 cases were identified. During the study tion could not be verified. Seven cases of debride-period, the national patient administrative system ment, which included exchange of the tibial poly-(PAS) was used to search for unreported revisions ethylene insert, were excluded since in the context – minimising the risk of unreported revisions, in of the study these operations were considered to be particular arthrodesis, extraction of the prosthesis, soft tissue operations and not true revisions. In 19 and amputation. Information on sex, age, primary cases, aseptic revisions were wrongly recorded as diagnosis, primary operation, and revisions was infected revisions.

gathered from the database of the registry. Infor-

Patients. 478 first-time revisions of primary

mation on co-morbidities, wound complications knee arthroplasties due to infection remained for after the primary operation, type of infection, the study. An overview of patient allocation is given infecting pathogen, its antimicrobial susceptibil-

in Figure 11. Six patients had both knees revised

ity pattern, surgical and antimicrobial treatment, because of infection and each knee was regarded

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

as a separate case. Osteoarthritis (OA) was the pri-

of deep infection. In 11 cases, it was not possible

mary diagnosis in 299 patients (302 cases), rheu-

to determine the exact date of diagnosis from the

matoid arthritis (RA) was the primary diagnosis hospital records. in 140 patients (143 cases), and other disease was

The type of infection was determined based on

the primary diagnosis in 33 patients (33 cases). both clinical appearance and timing. An acute hae-Regarding gender, 54.6% of the OA cases and matogenous infection was defined as an infection 67.8% of the RA cases were females. Today, OA is occurring acutely around a formerly uninfected the predominant indication for knee arthroplasty; knee arthroplasty, irrespective of the time from pri-however, during the time of the study, patients with mary arthroplasty until diagnosis of infection. To RA made up a larger proportion of those being be classified as an acute haematogenous infection, operated (Figure 1). A modified Charnley's classi-

it had to be clear that there was an interval without

fication for the knee (Charnley 1979, Dunbar et al. signs of infection between the primary arthroplasty 2004) was used as an estimate of co-morbidity and and the occurrence of infection. Deep infections the patients were classified as group A (disease in that occurred after surgical intervention other than the index knee only), group B (bilateral knee dis-

revision or through direct spreading from an adja-

ease), or group C (remote arthritis and/or a medical cent traumatic wound into the joint, or after an condition that affected their ability to ambulate). arthrocentesis, were classified separately as sec-14% of the patients were noted to have diabetes.

ondary infections. The remaining infections were

The primary operations were performed at classified according to the time of diagnosis into

75 orthopaedics departments, the first in 1976 early infections (≤ 3 months from primary arthro-(4 cases) and the most recent in 2000 (11 cases). plasty), delayed infections (between 3 months and There were 389 TKAs (81.4%), 65 UKAs (13.6%), 2 years), and late infections (more than 2 years). In 4 combined medial and lateral UKAs (0.8%), 17 paper I, these remaining infections were even clas-hinged prostheses (3.6%), and 3 femuro-patellar sified as early post-operative infections (≤ 4 weeks) prostheses (0.6%).

and late infections (> 4 weeks), after those infec-

Bone cement was used for fixation in 96% of tions diagnosed at a presumed aseptic revision had

cases, but information about the type of cement been classified separately. In 9 cases, based on the used was available in only 45% of cases; of these, existing information, it was not possible to deter-90% contained antibiotic. Information on the type mine the type of infection.

of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis used could not

Re-operation prior to the index operation was

be extracted from the hospital records, but the most defined as any operation at the knee joint that did not commonly used antibiotic prophylaxis in Sweden involve exchange, addition, or removal of a pros-has been cloxacillin (SHPR 2009).

thetic component, with the exception of exchange

Information about wound complications was of the tibial insert in conjunction with debride-

gathered from the hospital records, and it was ment. In 220 cases (46.0%), re-operations were available in 444 cases (92.9%). To be recorded as a performed after the diagnosis of a deep infection wound complication, the wound disturbance had to and before the index operation. Continuous lavage have occurred during the first 30 days after primary was most common (116 cases), followed by deb-operation and had to have been noted before deep ridement (43 cases, 4 of which included exchange infection was diagnosed. The wound complica-

of the tibial insert), arthroscopy (31), wound revi-

tions were classified as culture-positive incisional sion (16), lavage (13), extirpation of a sinus tract SSI, prolonged wound drainage, skin necrosis, (8), and incision and drainage (4). The time from wound rupture, prolonged wound healing, bleed-

the diagnosis of infection until the re-operation was

ing, and inflammation.

less than 4 weeks in 205 cases (93.2%).

The time of infection was defined as the date on

The index operations were performed at 59

which the treating surgeon considered the knee to orthopaedics departments throughout Sweden be deeply infected. This date did not always coin-

(approximately 1 operation every other year), the

cide with the time of appearance, as there could first in 1986 (n = 24), and the most recent in 2000 be a reluctance to correctly interpret obvious signs (n = 41). The index operations were categorised

Anna Stefánsdóttir

as either one-stage revisions, two-stage revisions, how many patients received antibiotics before arthrodeses, extractions, above-the-knee amputa-

sampling for culture.

tions, or other operations. Unconventional surgical

For species identification we relied on the cul-

treatments, such as partial revision or the use of ture reports from the microbiology departments the same components after re-sterilisation, were and statements in the medical records. In some grouped as other operations.

cases, only the type of bacterium (for example

Antibiotics were widely used, both before and "anaerobic Gram-positive coccus") or the genus

after the diagnosis of a deep infection, but the (for example, Enterococcus sp. or Staphylococ-information in the hospital records was unreliable. cus sp.) was given. The antibiotic susceptibility Better information was available on the use of anti-

reported by the microbiological laboratories as S

biotics after the index operation, and in 17 cases a (sensitive), I (intermediate), or R (resistant) was combination including rifampicin was used.

noted. Isolates of the same bacterial species were

Microbiology. 52 cases were excluded from not tested against the same antimicrobial agent in

the study on microbiology (paper II). In 41 cases, all the microbiological laboratories, or throughout no information on microbiological findings was the study period. Reported susceptibility to PcV available and in 4 the information was based on and PcG is reported together as susceptibility to culture from a sinus tract, which is regarded as an Pc. Staphylococcal isolates were variously tested unreliable type of culture. In 7 cases, the patient for susceptibility to oxacillin, dicloxacillin, cloxa-record included information on microbiology but cillin, or simply isoxazolylpenicillins. An isolate the treating doctor had judged that the findings tested against one of these agents was considered reported had no clinical relevance.

to be S, I, or R to isoxazolylpenicillins and those S.

Culture reports were available for study in 288 aureus that were R were called methicillin-resist-

of the 426 cases. Six were excluded, as the micro-

biological findings in the culture report had been

When performing statistical analysis, the patho-

judged by the treating doctor to be without any gens were divided into 9 groups: S. aureus, CNS, clinical relevance and these findings were not in streptococci, other aerobic Gram-positive bacteria, agreement with other information on microbiol-

Gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, other patho-

ogy reported in the medical record. In 19 cases, gens, polymicrobial infections, and negative cul-the culture was reported negative. Of the 263 cases tures.

remaining, 21 had a polymicrobial infection (18

Result of treatment. To evaluate the results of

with 2 pathogens and 3 with 3). In one case, two treatment, 2 end-points were determined. Firstly, S. aureus isolates with different susceptibility pat-

the re-revision rate due to infection was gathered

terns each grew in 4 of 5 tissue samples collected from SKAR. All cases could be followed concern-during surgery, and in 8 cases two or more strains ing further revision from the date of index opera-of CNS were cultured from at least 2 tissue sam-

tion – or in the case of a two-stage revision arthro-

ples each. Of the 296 isolates no susceptibility pat-

plasty or arthrodesis from the date of stage 2 – until

tern was reported for 11, leaving 285 isolates for the date of death or until closure of study at the end study on antimicrobial susceptibility pattern.

of 2006. The median follow-up time with respect

The microbiological findings were based on to re-revision was 7.9 years, with a range from 17

tissue cultures in 221 cases, on synovial fluid cul-

days (due to death early after index operation) to

ture (gained either from knee aspiration or during 21.4 years. Re-arthrodesis of an infected arthrod-surgical revision) in 165 cases, and on wound cul-

esis and above the knee amputation after an extrac-

ture in 21 cases; in 19 cases, the type of culture was tion was considered as re-revision, despite that the unknown. The decision to include wound cultures operation did not include removal of a prosthetic was based on the findings of Cuñé and co-workers component.

(Cuñé et al. 2009). Most of the wound cultures

Secondly, the rate of failure to eradicate infec-

were from early infections, and excluding these tion was determined by adding information from cases would have led to a bias because of miss-

the hospital records on failed but not re-revised

ing information on early infections. It is not known cases to the re-revision rate. It is difficult to dif-

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

ferentiate between persistent infection and new interval between stage 1 and 2 and the state of the infection, especially retrospectively. Furthermore, joint during the interval was analysed. Those cases it can be argued that for the individual patient it is with failure to eradicate infection were compared of no importance whether the infection is a persist-

with cases without failure to eradicate infection.

ent or a recurrent one. Thus, all infections diag-

Time trends were studied by dividing the study

nosed after the index operation were regarded as a period into three 5-year periods, with the index failure to eradicate infection. In some cases, life-

operation performed 1986–1990, 1991–1995, or

long antibiotics were prescribed, but if no clinical 1996–2000. In paper II, the period was divided

signs of infections were detected these cases were depending on the date of culture.

not regarded as failures. The follow-up time with

respect to failure to eradicate the infection was

calculated as the time from the date of the index Paper IV

operation – or in the case of a two-stage revision arthroplasty or arthrodesis from the date of stage In 114 consecutive cases treated at the department 2 – until date of revision, death, or the latest avail-

of Orthopaedics, at Lund University Hospital,

able information in the medical records. Optimally, during 2008 the time of administration of preoper-the follow-up time should be at least 1 year after ative prophylactic antibiotic in relation to the start conclusion of antibiotic treatment but due to the of surgery was recorded from the operation report. retrospective nature of this part of the study, this The information was collected without the involve-could not always be accomplished. The median ment or knowledge of the staff who administered follow-up time regarding failure to eradicate the the prophylactic antibiotic. According to local infection was 2.1 years, with a range from 0 to 16.9 guidelines, patients should have the preoperative years. 80% of the one-stage revisions and 74.7% prophylactic antibiotic 30 minutes before the start of the two-stage revisions were followed in this of surgery but administration within a time interval respect for more than a year whereas only 54.9% from 45 minutes to 15 minutes before start of sur-of the arthrodesis patients and 27.6% and 16.7% gery was regarded as adequate.

of those with extractions and amputations, respec-

The timing of prophylactic antibiotics was not

tively, could be followed for more than a year. It is registered in the SKAR before 2009. To search possible that patients with persistent infection (that for this information, 300 cases were randomly was not revised) were treated at a department other selected from the 9,238 primary TKAs registered than the one that performed the index operation, in the SKAR as having been performed during and were thereby missed.

2007 because of osteoarthritis. The anaesthetic

Mortality. The 1-year mortality was determined record was requested from the operating unit and

based on information from the Swedish Cause of 291 reports were received. Four patients had both Death Register (Statistics Sweden).

knees operated on the same day; in 3 cases, the

Prognostic factors. When searching for factors knee selected for study was the first one and in 1

that affected outcome, the analysis was restricted to case it was the second. Information on the type and those cases that were treated with revision arthro-

dose of prophylactic antibiotic, as well as the time

plasty in one or two stages. The variables that were of administration in relation to the inflation of a tested were: sex, primary diagnosis, age at index tourniquet and to the start of surgery, was searched operation, Charnley group, the presence of diabe-

for in the anaesthetic record. Administration of

tes, the presence of wound complication(s) after prophylactic antibiotic more than 45 minutes primary operation, type of infection, type of patho-

before the start of surgery was regarded as inad-

gen, occurrence of re-operation before the index equate because of the short half-life of the most operation, time from diagnosis to index operation, commonly used antibiotics. Administration later one- or two-stage revision, year of index operation, than 15 min before the start of surgery was also the region in which the index operation was per-

regarded as inadequate, as in most cases the infu-

formed, and use of rifampicin in antibiotic treat-

sion would not have entered the circulation at the

ment. For two-stage revision, even the length of the time of incision or inflation of a tourniquet.

Anna Stefánsdóttir

It was assumed that censored cases had the same

risk of re-revision or failure to eradicate infection

Paper I. The Chi-square test was used to compare as those that were not censored. This assumption proportions.

might be untrue, as it is possible that dying and

Paper II. The Chi-square test was used to evalu-

failure to eradicate infection were competing risks.

ate the distribution of microbiological findings.

For statistical evaluation of categorical factors

Cuzick's test for trend (a Wilcoxon-type test for that could be prognostic of outcome, Kaplan-Meier trend across a group of three or more independent curves were calculated separately for each group random samples (Cuzick 1985)) was used to evalu-

and the log rank test used to evaluate whether there

ate changes over time in antibiotic susceptibility were differences in survival. For continuous vari-pattern.

ables, Cox regression analysis was used.

Paper III. The Chi-square test was used to com-

Paper IV. The 95% confidence interval for pro-

pare proportions. The Kaplan-Meier method was portions was calculated as ± 1.96 standard errors.

used to calculate the cumulative re-revision rate for

For all statistical evaluations, the significance

infection and the cumulative rate of failure to eradi-

level was set at p < 0.05.

cate infection for those treated with two-stage revi-

The statistical analyses were performed using

sion. Censoring events were death and re-revision the software packages PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS, for reasons other than infection (aseptic revision or Chicago, IL) and STATA version 11.1 (Stata Corp above-the-knee amputation due to atherosclerosis). LP, College Station, TX).

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

Results / Summary of papers

of infection (30.3%), followed by delayed infec-

Paper I: The time and type of deep

tion (between 3 months and 2 years, 28.4%) and

infection after primary knee arthroplasty

acute haematogenous infection (22.0%). Using

In 478 cases of first-time revisions due to infection, the classification system proposed by Segawa and during the years 1986–2000 the time from primary co-workers, late (chronic) infection was the most knee arthroplasty until the diagnosis of deep infec-

common type of infection (59.9%), followed by

tion was found to range from 3 days to 21.3 years. acute haematogenous infection (22.0%), and only Two-thirds of the infections (317 cases) were 52 cases (11.1%) were diagnosed as early postop-diagnosed within 2 years of primary arthroplasty erative infections; that is, ≤ 4 weeks after primary (Figure 12). Of those that were diagnosed within knee arthroplasty. 2 years, almost half of the cases (143 of 317) were

In 186 cases, a wound problem was noted during

diagnosed within 3 months (Figure 13).

the first 30 postoperative days, before deep infec-

Acute haematogenous infections were found to tion was diagnosed. The incidence of wound com-

occur at all times after primary arthroplasty, and plications varied depending on the type of infec-could not be classified as a subgroup of late infec-

tion. When using Zimmerli's classification, this

tion. Infections occurring after surgical interven-

varied from 7.4% and 8.7% in those with second-

tion other than revision or through direct spread ary and acute haematogenous infection, respec-from an adjacent traumatic wound into the joint, tively, to 17.2% in those with late infection, and or after an arthrocentesis, did not fit in to the exist-

57.1% and 61.3% in those with delayed and early

ing classification systems and were classified sepa-

infection. The most common type of wound com-

rately as secondary infections. Using the classifica-

plication was wound drainage (n = 74), followed

tion system proposed by Zimmerli and co-workers, by culture-positive superficial surgical site infec-with the modification that acute haematogenous tion (44), skin necrosis (25), wound rupture (21), infections could occur at all times and that sec-

inflammation (15), prolonged wound healing (5),

ondary infections were classified separately, early and bleeding (2). infection (≤ 3 months) was the most common type

positive culture at revision

positive culture at revision

acute haematogenous

acute haematogenous

other (early, delayed, late)

other (early, delayed, late)

Years since primary arthroplasty

Months since primary arthroplasty

Figure 12. The number of deep infections diagnosed

Figure 13. The number of deep infections diagnosed

each year after primary knee arthroplasty, shown

each month during the first 2 years after primary knee

according to type of infection, in 467 cases that were

arthroplasty, shown according to type of infection, in

revised due to infection in Sweden, 1986–2000.

317 cases that were revised due to infection in Sweden, 1986–2000.

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Negative culture

Polymicrobial Other

Gram-negative bacteria Other aerobic Gram-positive bacteria

Streptococcus spp.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci

Staphylococcus aureus

Figure. 14 The microbiological spectrum of infected primary knee arthroplasties surgi-cally revised in Sweden during 1986–2000, divided into 3 periods based on the date of culture.

lowed by streptococci (19/99, 19.2%) and Gram-

Paper II: Microbiology of the infected

negative bacteria (8/99, 8.1%). The most common

knee arthroplasty: Report from the

pathogens in polymicrobial infections were CNS,

Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register on

Gram-negative bacteria and Enterococcus spp.

426 surgically revised cases

Only 1 of 84 S. aureus isolates (1.2%) tested

The microorganism most commonly found in against isoxazolyl penicillins was resistant 426 cases of infected primary knee arthroplasties (MRSA). Sixty-two of 100 CNS isolates (62%) revised due to infection, during 1986–2000, was tested against isoxazolyl penicillins were resistant. Staphylococcus aureus, which was the sole causa-

Gentamicin resistance was found in 1 of 28 tested

tive pathogen in 30.5% of cases, followed by coag-

isolates of S. aureus (4%) and 19/29 tested isolates

ulase-negative staphylococcus (CNS), which was of CNS (66%).

the sole pathogen in 27.5% of cases. Streptococcus

The microbiology was found to change signifi-

accounted for 8.4% of the infections, Enterococcus cantly during the period studied (p = 0.019) (Figure spp. for 7.7%, Gram-negative bacteria for 6%, and 14). The proportion of infections caused by S. anaerobic bacteria for 2.7%. In 6.3% of cases more aureus decreased from 46.3% during 1986–1990 than one pathogen was cultured (polymicrobial to 27.6% during 1996–2000. At the same time, infections), and in 9.2% the cultures were negative. the proportion of infections caused by enterococci

The microbiological spectrum varied considera-

increased. No enterococcal strains were cultured

bly depending on the type of infection (p < 0.001). before 1991 and of the 33 strains cultured, 21 were CNS was the most common pathogen in early, isolated in 1996 or later.

delayed, and late infections (105/229, 35.1%), fol-

The reported methicillin resistance among CNS

lowed by S. aureus (55/299, 18.4%), whereas S. increased during the period studied (p = 0.002), aureus was the most common pathogen in acute with 0/6 reported resistant in 1990 or earlier, 18/31 haematogenous infections (67/99, 67.7%), fol-

during 1991–1995, and 45/63 during 1996–2000.

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

Two-stage, 12 (3)

Aseptic revision, 2

Arthrodesis, 16 (3)

Re-arthrodesis, 2 (1)

Two-stage, 281 (22)

Extraction, 5 (1)

aseptic causes, 3

Aseptic revision, 13 (1)

Partial one-stage, 1 (1)

Planned two-stage

Extraction only, 8

Infected primary

Re-arthrodesis, 1

knee arthroplasties

One-stage, 45 (1)

Extraction, 1 (1)

Aseptic revision, 3

Arthrodesis, 103 (7)

Re-arthrodesis, 3

Planned arthrodesis

Extraction only, 2

Figure 15. Flow chart showing revisions per-

Extraction, 19 (1)

formed in 478 cases of infected primary knee arthroplasty. The numbers of cases in which

infection was not eradicated but further sur-gery was not performed are given in paren-

Aseptic revision, 1

Cumulative rates (Kaplan-Meier)

Paper III: 478 primary knee arthroplasties

revised due to infection – a nationwide

failure to eradicate infection rate

During the period 1986–2000, two-stage revision

arthroplasty was the most commonly used surgical

treatment for infected primary knee arthroplasty

in Sweden (289/478, 60.5%) (Figure 15). There

were regional differences in type of treatment. The highest proportion of patients treated with revision

arthroplasty (one- or two-stage) was in the western

region (78%), and the lowest in the northern region

(61%). The highest proportion of patients treated

Years after index operation

with an arthrodesis was in the northern region (33%), and the lowest was in the western region Figure 16. The cumulative re-revision rate and rate of

failure to eradicate infection after 281 two-stage revi-

(12%). 40% of the one-stage revisions were per-

sion arthroplasties performed in Sweden, 1986–2000.

formed in the southern region. The proportion of patients undergoing revision arthroplasty increased was 9.4% (95% CI 6.5–13.5) at 2 years and 12.7% from 59.6% in the period 1986–1990 to 75.3% (95% CI 9.2–17.8) at 5 years. The cumulative rate during 1995–2000, and the proportion of patients of failure to eradicate infection was 17.8% (95% having an arthrodesis decreased from 27.3% in CI 13.3–24.0) at 2 years and 27.5% (95% CI 1986–1990 to 19.5% in 1995–2000.

21.3–38.3) at 5 years (Figure 16). Arthrodesis was

After a two-stage revision arthroplasty, the the most common surgical method used when re-

cumulative re-revision rate because of infection revising an infected knee arthroplasty (Figure 15).

Anna Stefánsdóttir

The only factor that was found to be predic-

Number of cases

tive of failure to eradicate infection after a revi-sion arthroplasty (one- or two-stage) was a his-

tory of wound complication after the primary operation and before deep infection was diagnosed (p = 0.005). The risk of failure to eradicate infec-

tion was doubled for those with a history of wound complication after primary arthroplasty compared

to those who did not have a history of wound com-plication (RR = 2.04, 95% CI 1.23–3.39). Of the 34

cases with wound complication and where there was a failure to eradicate infection, 31 were early or delayed infections.

-150 -120 -90 -60 -30

In 59 of the 281 two-stage revisions that were

Minutes before/after inflation of tourniquet

completed, and in 5 of the 45 one-stage revisions, Figure 17. The timing of administration of prophylactic infection was not eradicated. The difference was antibiotic in relation to the inflation of a tourniquet not significant (p = 0.150), but it is questionable in 176 cases of primary TKA. Zero represents the start

of surgery. The green bars correspond to acceptable

whether comparison should be made because of timing.

differences in selection.

A spacer block made of antibiotic-loaded

PMMA was the most commonly used method for pital, initiated by a local strategic program against local antibiotic treatment and stabilisation of the antibiotic resistance, signalled that the timing of joint during the interval between stage 1 and stage administration was inadequate. To verify these 2. Using both PMMA beads and a spacer gave results and to test the hypothesis that the timing a lower rate of failure to eradicate infection, but was inadequate even at other departments, a larger compared to spacer the difference was not statisti-

study was conducted in Lund, and 291 cases ran-

cally significant (p = 0.123).

domly selected from the SKAR – from the 9,238

The most commonly used technique to accom-

primary TKAs reported to have been performed

plish an arthrodesis was external fixation, which because of OA during 2007 – were studied .

was used in 79 cases, 38 of which were done in a

Of the 114 patients studied in Lund, only 51

two-stage manner. An intramedullary rod was used (45%, 95% CI: 36–54%) received the first antibi-in 21 cases, 17 of which were done in 2 stages. otic dose of antibiotic between 45 and 15 minutes In 2 cases, the joint was stabilised with pins (one-

before the start of surgery. In 22 cases (19%), sur-

stage), and in 1 case it was stabilised with a plate gery was started at the same time or before admin-and screws (two-stage).

istration of prophylactic antibiotic. In the material

The 1-year mortality for those patients treated from the SKAR, the time of administration of the

with extraction of the implant or above-the-knee first doses of antibiotic prophylaxis could be ascer-amputation was high.

tained from the anaesthetic record in 198 cases. Only 113 patients (57%, CI: 50–64%) received the antibiotic between 45 and 15 minutes before the start of surgery. The mean time was 41 min-

Paper IV: Inadequate timing of prophy

utes, with a range from 105 minutes before the

lactic antibiotics in orthopedic surgery.

start of operation to 120 minutes after the start. In

We can do better

176 cases, it was possible to read the time from

As the effect of prophylactic antibiotics is related administration of prophylactic antibiotic until the to the timing of administration, it is important to time of inflation of a tourniquet. Only 94 (53%, CI: follow how the routines with preoperative prophy-

46–61%) received antibiotics between 45 and 15

lactic antibiotics are working. A small study at the minutes before the tourniquet was applied (Figure Department of Orthopaedics, Lund University Hos-

17). The mean time was 40 minutes, with a range

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

from 153 minutes before the inflation of a tourni-

Information on type of antibiotic used was avail-

quet to 120 minutes after inflation.

able in 247 cases (85%), and of these 89% had

In 2 of the 4 bilaterally operated patients, no received cloxacillin, 9% clindamycin, and 2%

additional antibiotic was given before the start of cefuroxime. The most common dose of cloxacillin surgery on the second knee.

was 2 g (158/212 patients, 75%).

Anna Stefánsdóttir

Deep infection after a knee arthroplasty is a Timing and type of infection

demanding and growing problem (Kurtz et al. 2007). In papers I–III, a large number of primary There have been relatively few reports involv-knee arthroplasties that were surgically revised due ing all infected knee arthroplasties, and not only a to an infection, during the years 1986–2000, were subgroup of patients (Walker and Schurman 1984, identified by searching the Swedish Knee Arthro-

Grogan et al. 1986, Bengtson et al. 1989, Bengtson

plasty Register (SKAR). The information was used and Knutson 1991, Rasul et al. 1991, McPherson et to determine the timing and type of infection, the al. 1999, Segawa et al. 1999, Peersman et al. 2001, microbiology and antimicrobial resistance pattern, Husted and Toftgaard Jensen 2002, Laffer et al. and the type of treatment and results thereof. The 2006, Pulido et al. 2008). In these studies, the onset strength of the study is that it covered all revisions of infection was reported to be within 3 months of performed, irrespective of type of hospital, type of surgery in 29–46% of cases and within 4 weeks in infection, or type of treatment. In paper IV, a spe-

3–48% of cases. The proportion of haematogenous

cific and important part of the preventive measures infections varied from 6% to 49%. There are sev-was studied – i.e. the timing of administration of eral methodological differences between the stud-the first dose of prophylactic antibiotic.

ies, which is why comparisons should be done with caution. The largest study, involving 357 cases oper-ated during 1975–1985, was an earlier study from the SKAR where 46.5% of the infections were diag-

Limitations of the study

nosed within 3 months of primary arthroplasty; 25%

The major drawback of the study is that not all were reported to be of haematogenous origin, and in infected knee arthroplasties were included. An 40% of cases the primary diagnosis was RA (Bengt-unknown number of patients were treated with-

son and Knutson 1991). Today, the overwhelming

out revision of the prosthetic components, and majority of patients who undergo knee arthroplasty were thereby not reported to the register. Those have OA (Figure 1), and as the most common type who were not included may have been the frail or of infection in OA patients was early infection, this elderly patients, those who refused surgery, those type of infection is probably even more common who were treated with suppressive antibiotics, now than during the study period.

or those with soft tissue operation only. It is not

As there is no clear evidence for the statement

possible to predict the effect of these cases on the that infections with a duration of less than 4 weeks overall result. In addition, it is probable that infec-

can be treated with debridement, there is no reason

tions caused by low-virulence organisms were (to to classify the infections as early postoperative (≤ an unknown extent) not diagnosed as being septic 4 weeks) and late (> 4 weeks). Classification of during revision and were therefore not reported. infections as early (≤ 3 months after the primary Data on some of the variables were collected retro-

arthroplasty) and delayed (3 months to 2 years)

spectively, which could have affected the reliabil-

highlights the pathogenesis and the general belief

ity. The information gathered was not complete in that most infections are acquired during or shortly all cases, and some data were less available during after surgery, but may not be detected until later. the first years of the study. In addition, no infor-

The high incidence of wound problems in those

mation was available on several factors that may with delayed infection supports this view. Wound have affected the outcome, with the state of the soft complication is a well known risk factor for later tissues around the knee, complete information on diagnosis of deep infection (Berbari et al. 1998, co-morbidities, and smoking habits probably being Abudu et al. 2002, Saleh et al. 2002, Phillips et the most important ones.

al. 2006, Galat et al. 2009), but surprisingly little

THE INFECTED KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

guidance can be found in the literature regarding aureus was the infecting pathogen in 6/15 (40%) optimal treatment (Vince and Abdeen 2006) and (Fulkerson et al. 2006).

the results of treatment (Galat et al. 2009).

The proportion of polymicrobial infections was

Acute haematogenous infections should be clas-

in accordance with that in other studies (Peersman

sified separately, irrespective of the length of time G 2001, Pulido et al. 2008), and as described ear-from primary operation. Furthermore, we defined a lier, polymicrobial infections were most common group of secondary infections that should be clas-

in early infections (Marculescu and Cantey 2008).

sified separately.