Waste management plan for the maltese islands 2013 – 2020 – consultation document

WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN

FOR THE MALTESE ISLANDS

A Resource Management Approach

Final Document

January 2014

Foreword It is my pleasure to be able to present Malta's Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands which covers the period up till 2020. We have purposely given this Plan a resource management approach for we firmly believe that waste is increasingly becoming a resource from which we do not only derive recycled materials, that lengthen the life cycle of virgin resources, or embedded energy but also a greener economy and the creation of more green jobs in line with the architecture of modern economies. I am proud at what we have been able to achieve in such a short time. Upon coming into office we found that we had a very tight deadline by when to submit Malta's Waste Management Plan and Waste Prevention Plan. I was firmly of the belief that success in this sector can only be achieved if society were to make the required commitment. To this effect the authors of this Plan agreed to undertake as wide a consultation exercise as possible during which we met interested stakeholders, initially, without any preconceived ideas and, later, put out a draft Plan for further consultation in parallel with an SEA which was being conducted pari passu with the development of this Plan. On paper, I am confident that the Plan will find the approval of a wide majority of society whatever walk of life they come from. However, the proof of the pudding is in the eating and this Plan's success on the ground can only be achieved if every member of society assumes his and her responsibility in committing to the national waste management agenda. What we are proposing is not any different from success stories in other fellow European countries and which have come about through multi-stakeholder commitments. Malta is a very small country where the impacts of environmental problems can be felt throughout the islands. Therefore no one can be detached from this problem. It is now time to turn this challenge into an opportunity. Better waste management practices, including minimizing our waste, will undoubtedly re-size the problem we are faced with, require less of an infrastructure and hence have a lower impact on the environment. An out of sight, out of mind approach can only lead to a more expensive waste management system and one where the cost of inaction is high. We have witnessed the concerns of those who live in the proximity of sites designated for waste management facilities. The consequence of inaction will mean that more of our limited land areas will have to be dedicated to such. This would clearly go against our obligation to bequeath to future generations an environment which is not undermined by the consequences of our irresponsible behavior. Government is committed as much on this agenda as it is on other aspects within the national context. My appeal is for you to embark upon this journey with us with a mindset that realizes that your effort is an investment for yourself, your family and your future generations. Leo Brincat Minister for Sustainable Development, the Environment and Climate Change

Structure of Waste Plan:

CONTENTS

Executive Summary.1

3.12 Involvement of the Private Sector . 166

WASTE PREVENTION

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Executive Summary

The core aim of this Plan is that of moving waste management in Malta up the waste

hierarchy through increased prevention, re-use, recycling and recovery. This depends

on a transformation of a variety of characteristics not least current population habits,

waste volumes generated, waste collection practices, waste infrastructure and output

markets. Malta's high population density, limited land space and lack of economies of

scale coupled with the effects of its climatic conditions, proves challenging to achieve

this aim.

Consultation

This document has been underpinned by an all-inclusive and multi-phased consultation

exercise.

An Issues Paper was initially launched by the Ministry for Sustainable

Development, the Environment and Climate Change on the 1 July and sought to identify the main issues characterising waste management in Malta with a view to eliciting feedback from stakeholders as to the potential solutions that may be adopted to address the identified issues.

This consultation ran for a period of six weeks between July and August 2013.

Subsequently, a second consultation exercise was conducted on the basis of the

Draft Waste Management Plan for a period of 8 weeks between October and December 2013.

Both consultation exercises gave the opportunities to interested parties to submit

proposals and set up meetings in order to discuss further both their own as well as Government's proposals.

Moreover, through internal consultation within Government the Plan:

presents a roadmap on the reform of the existing collection system which has

been developed in consultation with the Secretariat for Local Government following discussions with the Local Councils Association and a special consultation session for Local Councils;

takes on board the alignment of the Plan to the need of small and medium sized

businesses as guided by the Ministry responsible for the economy.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Waste Prevention Plan

The waste hierarchy ranks waste management options in an order commensurate with

their environmental impact. Waste prevention sits at the top of the waste hierarchy and

represents the most environmentally friendly option in that the absence of waste calls for

no management thereof. Malta's Waste Prevention Plan hinges upon:

heightening the awareness on the need to reduce waste arisings through

appropriate behavioural changes;

the reduction of municipal solid waste volumes;

reducing food waste;

increasing green public procurement to waste management;

understanding in more detail promotional and unaddressed mail;

undertaking efforts to limit construction and demolition waste.

Government has already issued an expression of interest for the provision of an

information and awareness campaign to accompany the implementation of the Waste

Management Plan.

Waste Management Plan

Malta's wider waste management plan, on its part, recognizes the need to meet a series of targets not least to reduce the generation of waste and to increase source separation so as to promote recycling and reduce landfilling. Malta is obliged to reach the following targets:

recycle 50% of paper, plastics, metal and glass waste from households by 2020;

only 35% (based on 2002 levels) of biodegradable municipal waste will be

allowed to landfill by 2020;

recover 70% of C&D waste by 2020;

collection of 65% of the average weight of electrical and electronic equipment

placed on the national markets by 2021;

for electrical and electronic equipment placed on the national markets achieve

55%, 70%, 80% and 85% re-use and recycling 75%, 80% and 85% recovery by 2018;

collection rates for waste portable batteries to reach 45% by 2016;

to re-use and recover 95 % of an average weight per vehicle per year by 2014.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

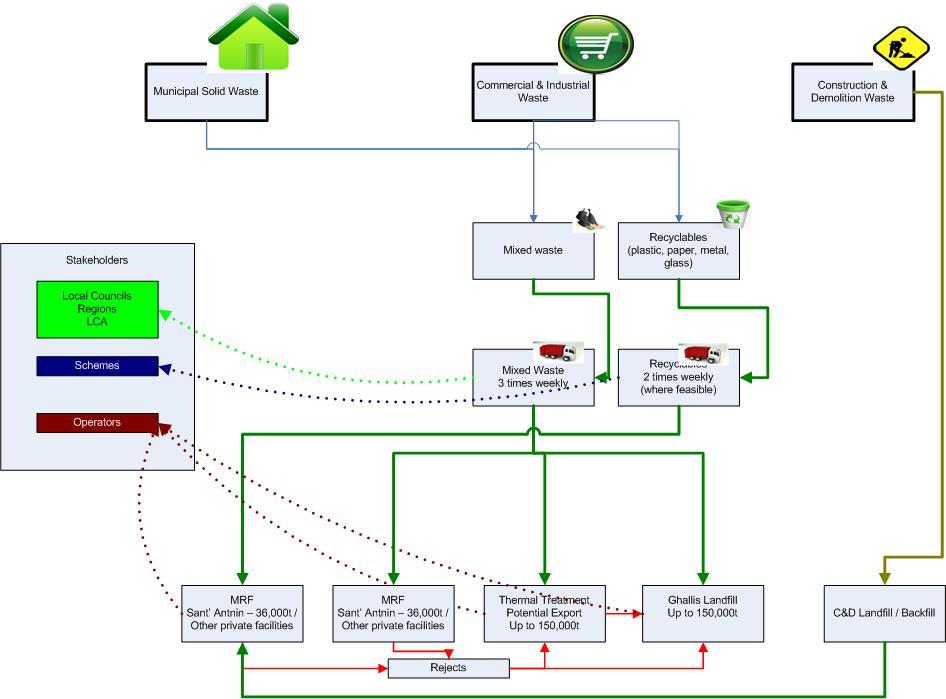

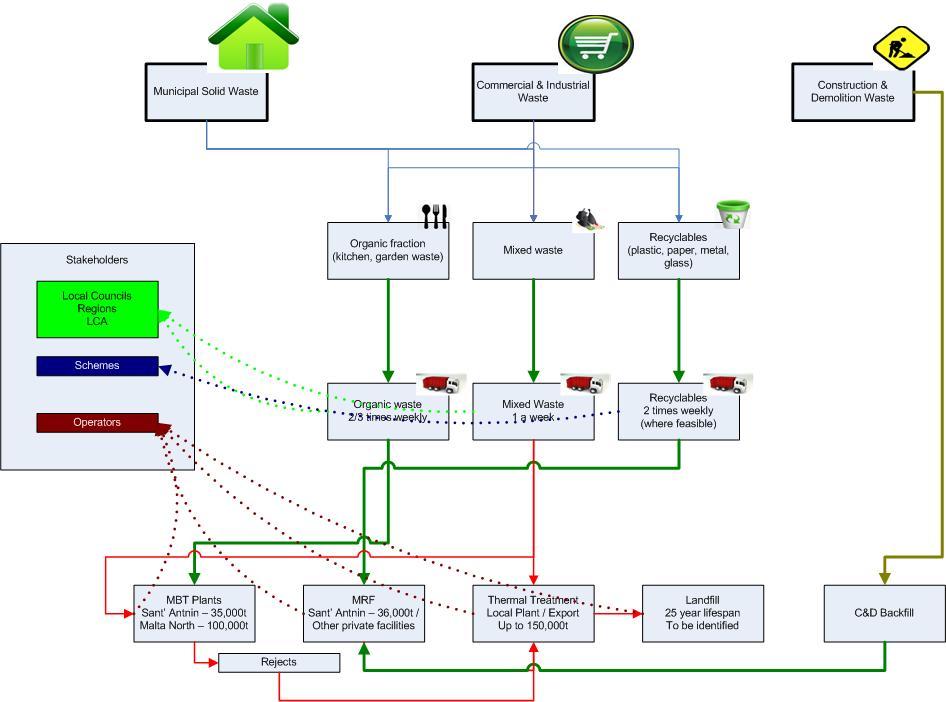

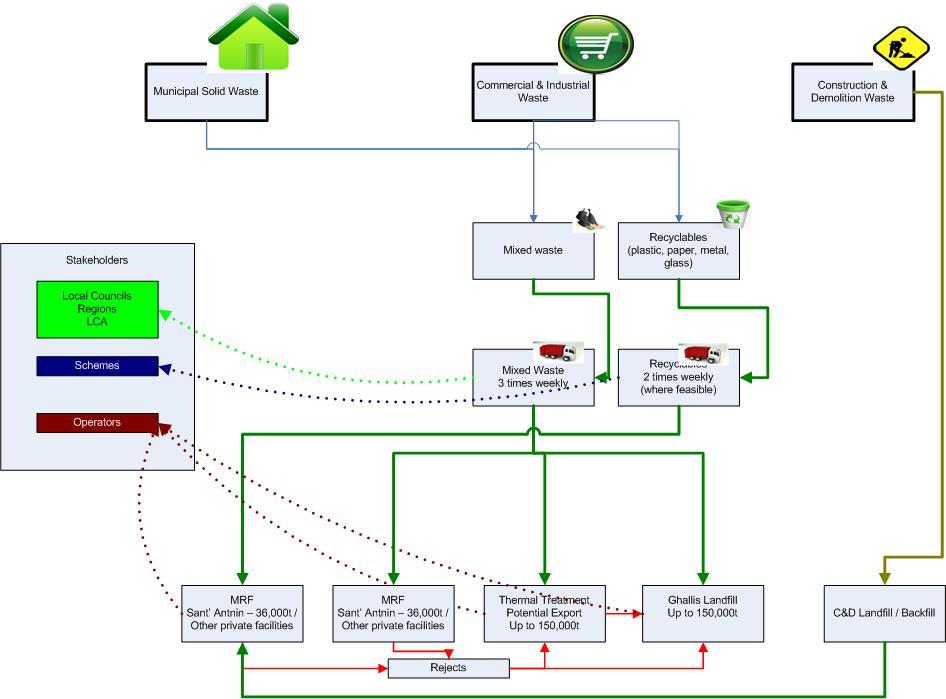

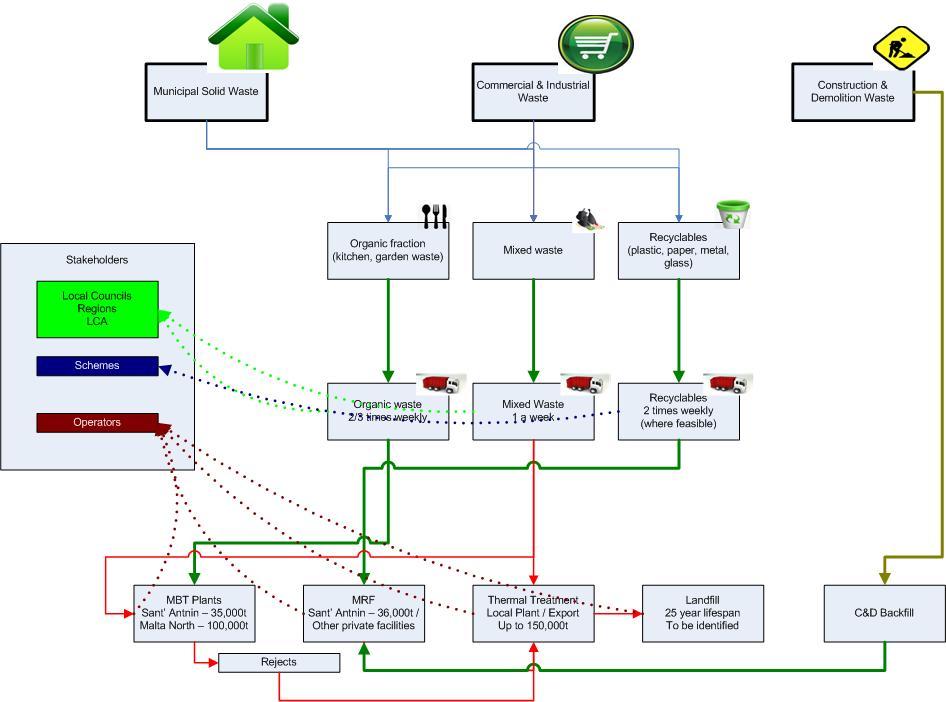

In order to address such obligations the Plan proposes the following initiatives:

undertake, in conjunction with the Secretariat for Local Government, a

wholesome review of the existing collection system so as to provide the existing and upcoming MBT plants with source separated organic waste, promote further recycling of plastic, paper, metal and glass at a household level and discourage the generation of mixed waste. This on the basis of the discussions held during the formulation of the Plan itself;

such restructuring needs to be completed by 2015 to coincide with the

completion of the Malta North MBT;

the introduction of a third collection of clear organic waste to improve the

performance of the MBT plants in Malta and in terms of Malta's obligation to reduce biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) going to landfill;

improve, at the earliest possible stage, the quality of waste to be directed to the

Sant' Antnin Waste Facility. This through piloting the separate collection of BMP in the south-eastern region;

piloting in various localities may serve to prepare us better for the post 2015

regularize the position of those commercial entities who are obliged to have their

own waste carrier but most of whom have, to date, rode on local council collection systems to the detriment of public finances;

develop potential solutions that will prevent the generation of C&D waste in

favour of maximizing the limestone resource;

revise the eco-contribution legislative framework in order to make it more

conducive to business, reduce administrative burden and encourage the setting up of more schemes;

replicate the success of producer responsibility schemes by encouraging the

development of new schemes in two other areas namely those related to waste from electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE and that related to batteries and accumulators;

undertake a cost benefit analysis to establish the most economically and

financially feasible option between local thermal treatment and the export of waste for energy recovery;

involve the private sector further in the waste management sector;

consider the setting up of a Waste Management Stakeholders Group in order for

Government to regularly engage interested stakeholders on the achievements and proposals being contemplated such that constant feedback may be sought from those directly involved in the sector;

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

accompany plan implementation with an ongoing national information and

awareness campaign;

beef up the enforcement capability;

independent auditing of schemes.

Sustainable waste management involves the identification of problem areas in the local waste management setup with a view to proposing a series of alternatives that would provide a net economic, social and environmental benefit. Compromising any of these three pillars of sustainable development would imply the compromising of sustainable waste management initiatives. The proposals being put forward in this Plan will prove futile unless society commits itself to investing some of its time to secure better waste management practices. This requires a collective effort that will make Malta more sustainable in its waste management practices. To this effect Government places a great deal of emphasis on the individual's need to alter existing behavioural patterns in order to reduce the amount of waste generated through more informed choices whilst separating the waste generated so as to maximize the amount of recyclables that are extracted therefrom. Government has tried to steer away from the introduction of new charges for waste management services on the basis of:

improved and more cost effective operations of waste management facilities;

the opportunity to recover additional value from the recycling of various waste

greater involvement of the private sector in waste management operations.

Government intends to review the progress achieved from economic, social and environmental standpoints within the first three years of implementation of this plan. It is therefore in the hands of society to make a success out of this Plan as befits the Maltese islands. This is our chance towards safeguarding the limited resources of our islands and leave behind a better environment to the younger and future generations.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Acronyms

AD – Anaerobic Digestion

BMW – Biodegradable Municipal Waste

CHP – Combined Heat and Power

EfW – Energy from Waste

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

MBT – Mechanical Biological Treatment

MEPA – Malta Environment and Planning Authority

MRF – Materials Recovery Facility

MSDEC – Ministry for Sustainable Development, the Environment and Climate Change

MFIN – Ministry for Finance

MSW – Municipal Solid Waste

MTP – Mechanical Treatment Plant

rBMW – residual Biodegradable Municipal Waste

RDF – Refuse Derived Fuel

rMSW – residual Municipal Solid Waste

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Terminology

Anaerobic digestion – the breakdown of organic material by bacteria in the absence of

oxygen, to generate combustible bio-gas and a digestate.

Biogas - a mixture of methane (50-75%) and carbon dioxide (50-25%) used to generate

heat and electricity.

Biodegradable Municipal Waste – Municipal waste that is capable of undergoing

anaerobic or aerobic decomposition, such as food and garden waste, and paper and

Combined Heat and Power – the use of heat energy to generate both electricity and

Composting - the biodegradation of organic matter, by microorganisms such as

bacteria, yeasts and fungi.

Digestate - a suspension of non biodegradable materials undigested organics, microbes

and microbial remains and decomposition by-products which is dewatered into a solid

and liquid fraction respectively known as digestate and liquor.

Energy from waste facilities - facilities that recover energy through thermal or

biological treatment of waste to generate heat and power. Thermal processes include:

incineration CHP, gasification and pyrolysis while biological processes include anaerobic

Gasification - Gasification involves the partial oxidation of waste at temperatures

typically above 750°C to recover energy and is considered as mid-way between

pyrolysis and incineration.

Landfilling – the disposal of waste onto or into land.

Municipal Solid Waste - Waste generated by households, as well as other waste which

because of its nature or composition is similar to household waste.

Materials Recovery Facility – Manual and/or mechanical separation of dry recyclables,

mainly paper, glass, plastics and metals collected separately or comingled, which are

bailed and sent for recycling.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Mechanical Biological Treatment - the mechanical separation of mixed waste and

biological treatment of the separated organic fraction.

Mechanical Treatment Plant – the mechanical separation of mixed waste.

Pyrolysis - Waste combusted in the absence of oxygen at temperatures of between

300°C to 800°C to recover energy.

Recycling – any recovery operation by which waste is reprocessed into products or

substances whether for the original or other purposes. It includes the reprocessing of

organic material but does not include energy recovery and the reprocessing of materials

that are to be used as a fuel.

Recovery – any operation the principle result of which is waste serving a useful purpose

by replacing other materials which would otherwise have been used to fulfil a particular

function, or waste being prepared to fulfil that function, in the plant or in the wider

Refuse Derived Fuel - organic components of municipal waste such as plastics and

biodegradable wastes that cannot be fermented are shredded and dehydrated to

produce a high calorific fuel.

residual Biodegradable Municipal Waste – that fraction of biodegradable waste

remaining following treatment.

residual Municipal Solid Waste – that fraction of municipal waste remaining following

Waste – any substance or object which the holder discards or intends of is required to

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

INTRODUCTION

Key Issues:

Low rates of recycling

High landfilling rates

Unsustainable waste management

Key Challenges:

To break the link between economic growth and waste

Moving waste up the waste hierarchy Moving towards sustainable waste management through waste

prevention, increased recycling and recovery

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

1. Introduction

Malta has for long relied on disposal as the main waste treatment operation. Moving

waste up the waste hierarchy through increased prevention, re-use, recycling and

recovery depends on a variety of factors mainly: population habits, waste volumes,

waste collection practices, waste infrastructure and output markets. Moreover Malta's

high population density, limited land space and lack of economies of scale coupled with

the effects of its climatic conditions, proves challenging to transform this small island

state into a competitive player within the waste sector.

Waste prevention is considered to be at the highest level of the waste hierarchy for

sustainable waste management. Through the minimisation of waste arisings as well as

the sustainable management of eventual waste generated, the Maltese government

aims to break the link between economic growth and waste production.

Although much more is yet to be done, to move away from excessive landfilling as well

as to enhance separation and recycling rates, the shift from unsustainable dumpsites

towards differentiated waste collection and treatment facilities clearly illustrates Malta's

initial efforts towards the achievement of sustainable waste management.

The Sant' Antnin waste treatment facility wil remain a pivot in Malta's waste

management infrastructure. Intentions to move waste up the hierarchy, towards

sustainable waste management practices, had prompted investment in a Mechanical

Biological Treatment / Anaerobic Digestion (MBT/AD) plant in the South of Malta with an

annual capacity of 36,000 tonnes of dry recyclables and 35,000 tonnes of organic waste

from the Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) stream. However certain plant inefficiencies

were not addressed and were the cause of certain operational deficiencies and

inconveniences. The new Government commissioned a report to analyse the operations

of the plant and which has pointed towards the importance of achieving greater

efficiencies as the plant had failed to generate the anticipated renewable energy. One of

the main causes for such was the quality of waste arriving from the ‘black bag' which

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

contains a heavy load of non-organic material. Notwithstanding the plant will remain a

pivot in Malta's waste management infrastructure. To this effect, improving the quality of

the throughout to this plant will be one of the crucial strategies to be adopted as it will

indirectly contribute to a better operation of the larger MBT plant at Ghallis which is

expected to come on stream during 2015.

Recovering energy from waste within existing and future facilities plays an important role

in sustainable waste management sector since it further values the concept of waste as

a resource. Waste contributes towards the European Union's Renewable Directive

targets, since, under this Directive, biodegradable waste qualifies as a renewable

Through public awareness campaigns and investing in the public and private sector,

Government is committed to continue addressing the challenge of moving waste

management options up the waste hierarchy.

1.1. Scope

Malta's first comprehensive waste strategy was that of 2001 which set out Government's

plans for upgrading the waste management sector. This plan was heavily influenced by

the gaps that prevailed at the time between the status quo and the expectations of Malta

as a future EU Member State. Thus the plan set out a roadmap which included

measures for the introduction of new legislation, development of new administrative

structures, economic measures, technical improvements and awareness raising

The first revision to this strategy occurred in 2009, five years after Malta's accession to

the EU. This revision was intended to be read in conjunction with the original strategy

for its aim was to fine tune Malta's way forward in the sector on the basis of the

experiences it had undergone to date. In addition Malta submitted its Waste

Management Plan 2008-2012 to the Commission in November 2009. In 2012, the

Commission had requested Malta to identify whether its Waste Management Plan was in

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

conformity with Article 28 of the Directive as part of its verification process. Malta

recognised that its Waste Management Plan:

addressed the analysis of the current waste management situation as well as the

measures to be taken to improve environmentally sound preparing for re-use,

recycling, recovery and disposal of waste and an evaluation of how the plan will

support the implementation of the objectives and provisions of the Directive;

addressed existing waste collection schemes and major disposal and recovery

installations, including any special arrangements for waste oils, hazardous waste

or waste streams;

did not provide an evaluation of the development of waste streams in the future;

required future work on future projections of MSW, C&D and C&I waste;

required revision to address new problems encountered since the adoption of the

plan in particular in respect of the need for new collection schemes, the closure

of existing waste installations and additional waste installation infrastructure;

did not include sufficient information on the location criteria for site identification

and on the capacity of future disposal or major recovery installations;

partially addressed general waste management policies, including planned waste

management technologies and methods, or policies for waste posing specific

management problems which were to be addressed in the revised plan;

partially addressed the fact that the Plan could have contained information about

the organisational aspects related to waste management including a description

of the allocation of responsibilities between public and private actors carrying out

waste management;

did not address the possibility of having the evaluation of the usefulness and

suitability of the use of economic instruments in tackling various waste problems;

partially addressed the possibility of including the use of awareness campaigns

and information provision directed at the general public or at a specific set of

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

did not address the possibility of addressing historical contaminated waste

disposal sites and measures for their rehabilitation.

Malta is obliged, under EU legislation, to submit a Waste Management Plan covering

different waste streams as well as a Waste Prevention Plan. In order to avoid having a

multitude of documents for the sector and to focus stakeholder attention, Government

has decided to merge the previous concept of separate documents, a Strategy, intended

for local policy guidance, and a Plan, intended for local policy guidance and compliance

to the Directive, within one National Waste Management Plan which is updated to reflect

the current scenario and project national interventions to achieve the 2020 targets.

Moreover, within this Plan, the Waste Prevention Plan is also being included to further

consolidate waste management policy within a single framework document.

This Plan represents government's planning document in respect of waste management.

It is intended to set out a holistic strategic direction in which Government envisaged the

sector to be taken forward. It is not the scope of this Plan to spell out each and every

detail associated with the Plan initiatives but to set a framework in which these initiatives

will be planned out in greater detail during the implementation phase and, during which,

the same collaborative approach will prevail. The Plan covers the different waste

streams in a holistic manner with a view to providing solutions which complement and

reinforce one another.

The structure of this document follows that of the document "Preparing a Waste

Management Plan" – A Methodological Guidance Note published by European

Commission, in 2012 and aims at addressing the gaps identified in the previous Plan.

It is envisaged that whilst the vision spelt out in this document is aimed at the 2020

scenario, regular updates, ideally at three year intervals, will be made to fine tune the

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

1.2. Disclaimer

The data presented in this document is based on that held by MEPA and the NSO. It is

recognised that further efforts are required to improve upon waste statistics not least in

ensuring that public and private stakeholders provide timely and accurate data which is

the foundation of robust waste statistics. Notwithstanding, the data available is

considered to be sufficient to enable the policy direction put forward in this document to

be properly motivated.

The National Plan for PCB/PCT which has already been approved and published shall

remain and shall be read in conjunction with this Plan.

1.3. EU policy and obligations

The European Union has a framework for regulating waste management within the

Community based upon the strategic objectives outlined in the Thematic Strategy1. The

Thematic Strategy was reviewed and on 19 January 2011 the Commission adopted a

Report on the Thematic Strategy on waste prevention and recycling (COM (2011) 13

Final). The report outlines the main forthcoming challenges and recommendations for

future actions which are mainly targeted to limit the generation of waste within the

Community as much as possible and particularly to decouple the increase in waste

generation from the increase in the economic prosperity of the Community. In this

context, EU waste management legislation is in the process of being updated to reflect

the findings of the report.

The EU issues legislation in the form of Directives, Regulations and Decisions aimed at

Member States, with the Waste Framework Directive 2008/98/EC being the most

important legal instrument. The EU has also a wide ranging body of other Directives that

address particular waste streams, such as packaging waste, end-of-life vehicles,

1 COM(2005) 666 final - Taking sustainable use of resources forward: A thematic Strategy on the prevention and recycling of waste.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

batteries, waste electrical and electronic goods, and also other Directives addressing

specific waste management options such as landfilling and incineration. The aim of

each and every single piece of legislation may be grouped as one, that is, to safeguard

human health and the environment for both present and future generations.

Compliance with such legislation led to:

several dump sites and incinerators being shut down across Europe, including

Malta, and subsequent cleaning of areas contaminated by such activities;

development of new techniques for the treatment of waste;

removal of hazardous substances from vehicles and electrical and electronic

equipment; reduction of dioxins and other emissions from incinerators; and

increased re-use, recycling and recovery of waste materials.

Moreover, European legislation led to a transition from waste being seen as a problem to

it being considered as a resource. Whether one agrees or not, sooner or later a culture

change needs to evolve where waste is not seen as a material intended primarily for

disposal but that waste is effectively managed using a resource based approach. Waste

has a value, as it can replace other materials which would have otherwise been used to

fulfil a particular function, from consumables to energy. Therefore, one's lack of

commitment and cooperation in separating his/her waste to recycle and recover

materials may be vital to future generations.

1.4. National policy

Malta's waste policy framework is guided by EU waste policy.

Malta's National Environment Policy (2012) states that in order to manage waste in an

environmentally sustainable manner, Government needs to ensure that the three pillars

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

of sustainable development (environmental, social and economic aspects) are taken into

consideration in decision-making in the waste sector.

The implementation of the EU waste Directives is in fact the principal aim for this sector

during the period covered by the NEP. National policy in the waste management sector

is based on four principles:

1. to reduce waste and to prevent waste occurring, with a view to achieving a zero-

waste society by 2050

2. to manage waste in accordance with the waste hierarchy, whereby it is recognised

that waste should be prevented or reduced, and that what is generated should be

recovered by means of re-use, recycling or other recovery options, in order to

reduce waste going to landfill, and to use the collection system to aid with

achieving these goals

3. to cause the least possible environmental impacts in the management of waste

4. to ensure that the polluter-pays principle is incorporated in all waste management

1.5. EU and National legislation

This section outlines the main legal instruments regulating waste applied both at

European and national level. Other applicable legislation emanating from the main

regulations is included together with a short description of the laws. This section is

divided into three sections as follows:

1. Framework Legislation (overarching all waste legislation)

2. Waste Treatment operations (legislation regulating waste treatment facilities)

3. Waste stream (legislation regulating specific waste streams)

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Framework Legislation

Waste Framework Directive

The Waste Regulations, 2011

(Directive 2008/98/EC)

(L.N. 184 of 2011)

Other applicable legislation:

Commission Decision 2000/532/EC establishing a European Waste List (EWC)

Commission Decision 2011/753/EU for verifying compliance with WFD targets

Council Regulation (EU) No 333/2011 on EoW scrap metal

Commission Regulation (EU) No 715/2013 on EoW copper scrap

The Directive establishes a framework for the management of waste across the

EU and incorporates provisions on the old directives on hazardous waste and on

waste oils. It lays down some basic waste management principles such as the

obligation to handle waste in a way that does not have a negative impact on the

environment and human health by managing waste sustainably in accordance with

the waste hierarchy.

A new concept which was introduced in the new Waste Framework Directive is the

‘end-of-waste' status which means that if a specific waste stream undergoes a

recovery operation, and fulfills specific criteria, it can cease to be waste, thus

obtaining the status as a product.

The Directive also introduces the ‘pol uter pays principle' and the ‘extended

producer responsibility' approaches, which involves the producer or that person

who put the product on the market to take care of the treatment of waste himself.

The Directive also stipulates a target of 50% re-use and recycling of household

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

waste and 70% recovery of C&D waste by 2020.

Furthermore, the new Waste Framework Directive integrated the provisions of the

former Hazardous Waste Directive (91/689/EEC) and Waste Oils Directive

(75/439/EEC) repealing them upon its entry into force.

The Waste Regulations of 2011, transposed from the Waste Framework Directive

2008/98/EC are the overarching national legislation on waste.

Waste Management

Waste Shipment Regulations

(Shipments of Waste) Regulations,

(EC No. 1013/2006)

(L.N. 285 of 2011)

Other applicable legislation:

Commission Regulation (EC) No 1418/2007 concerning the export for

recovery of certain waste to certain countries to which the OECD Decision on

the control of transboundary movements of wastes does not apply

Waste Shipments

Waste can have economic value and can be a useful source of raw materials.

Moreover, not all States can provide environmentally sound management of waste

within their territory. This is particularly true of Malta, a small State that does not

have the technical capacity and the necessary facilities, capacity or suitable

disposal sites in order to dispose of certain categories of waste in an

environmentally sound and efficient manner; hence the need to provide the

possibility for the shipment of waste from one State to another. This is called waste

shipment or transboundary movement of waste.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Waste shipment provides an option for valorising waste and for attaining

environmentally sound management of waste. Nevertheless, such transboundary

movements of waste from one State to another, often passing through other States

in the process, pose a potential threat to human health and the environment, and

therefore need to be controlled. There are many records of wastes being dumped

in States that were not capable to handle the wastes in an environmentally sound

For the purposes of shipment destined for recovery, waste is classified into two

categories: green, and red, the former being the least hazardous and the latter

referring to hazardous waste being the most hazardous. These two categories

correspond to two levels of controls. Green list waste is least controlled, while

hazardous waste is the most strictly controlled.

A basic requirement for waste shipment is a permit from the Competent Authority

of dispatch. In Malta this competency lies within the Malta Environment and

Planning Authority (MEPA). This permit is based on the prior notification, and in

most cases prior consent from the recipient State and all the States of transit with

respect to the particular waste entering their territory. Another requirement is for

the consignment to be covered by a financial guarantee or equivalent insurance

covering costs for shipment, including take-back where necessary, as well as costs

for disposal or recovery, in the case the shipment has not been completed as

planned or if it has been effected in violation of the EC Waste Shipment

Shipment of waste destined for disposal from Malta are only allowed to EU

Member States and EFTA countries which are also parties to the Basel Convention

(Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland).

Shipment of waste destined for disposal or recovery from Malta to ACP (Africa,

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Caribbean, Pacific) States are prohibited.

Shipment of hazardous waste destined for recovery from Malta are only allowed

to EU Member States and to countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Shipment of Green List waste destined for recovery from Malta are allowed to

EU Member States, OECD countries and certain non-OECD countries subject to

some restrictions for the latter.

Waste Treatment Operations

Industrial Emissions (Integrated

Pollution Prevention and Control)

Regulations, 2013

(L.N. 10 of 2013)

Industrial emissions Directive (IED)

Industrial Emissions (Waste

(Directive 2010/75/EU)

Incineration) Regulations, 2013

(L.N. 14 of 2013)

Industrial Emissions (Titanium Dioxide)

Regulations, 2013

(L.N. 13 of 2013)

Incineration Regulations

The aim of the incineration regulations is to prevent or reduce the pollution

generated by emissions into the air, soil, surface water and groundwater cause by

incineration and co-incineration of waste. This is to be achieved through the

application of operational conditions, technical requirements and emission limit

values for incineration and co-incineration plants within the EU dust, nitrogen

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2), hydrogen chloride (HCl), hydrogen fluoride

(HF), heavy metals and dioxins and furans.

Titanium Dioxide Regulations

These regulations are intended to regulate wastes arising from the titanium dioxide

industry. Even though there is no such industry locally, Malta as an EU Member

State was still required to transpose the provisions laid down the IED into national

Waste Management (Landfill)

Landfill Directive

Regulations, 2002

(Directive 99/31/EC)

(L.N. 168 of 2002)

Other applicable legislation:

Council Decision 2003/33/EC establishing waste acceptance criteria at

Landfill Regulations

The main objective of this regulation is to prevent landfilling, thus reducing the

adverse effect of the landfill of waste on the environment and human health. Local

regulations emanating from the EU Landfill Directive:

require that all waste should be treated prior to landfilling;

restrict the landfilling of certain waste streams;

require full cost recovery of landfill operations, waste acceptance procedures

and closure and after-care procedures.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

In addition to all of this, Member States are required to set a national strategy for

the diversion of biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) from landfills and sets the

following targets for the reduction of biodegradable municipal waste sent to landfill:

By 2010, 75% of the total amount (by weight) of biodegradable municipal

waste produced in 1995 or the latest year before 1995 for which

standardised Eurostat data is available.

By 2013, 50% of the total amount (by weight) of biodegradable municipal

waste produced in 1995 or the latest year before 1995 for which

standardised Eurostat data is available.

By 2020, 35% of the total amount (by weight) of biodegradable municipal

waste produced in 1995 or the latest year before 1995 for which

standardised Eurostat data is available.

Member States that landfilled more than 80% in 1995 or the latest year for which

standardised EUROSTAT data is available, of their collected municipal waste were

allowed to postpone the targets referred to above by a period not exceeding four

years. This was the case for Malta, and therefore the targets are to be achieved

by 2010, 2013 and 2020 respectively.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Waste Streams

Waste Batteries and Accumulators

Waste Management

Batteries Directive

(Waste Batteries and Accumulators)

(Directive 2006/66/EC)

Regulations, 2010

(L.N. 55 of 2010)

Other applicable legislation:

Directive 2008/12/EC, as regards the implementing powers conferred on the

Directive 2008/103/EC as regards placing batteries and accumulators on the

Commission Decision 2008/763/EC establishing, a common methodology for

the calculation of annual sales of portable batteries and accumulators to end-

Commission Decision 2009/603/EC establishing requirements for registration

of producers of batteries and accumulators

Commission Decision 2009/851/EC establishing a questionnaire on the

implementation of batteries and accumulators and waste batteries and

accumulators Directive

Commission Regulation (EU) No 1103/2010 establishing, rules as regards

capacity labelling of portable secondary (rechargeable) and automotive

batteries and accumulators

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Commission Regulation (EU) No 493/2012 of 11 June 2012 laying down,

detailed rules regarding the calculation of recycling efficiencies of the recycling

processes of waste batteries and accumulators

The batteries regulations

The Batteries Directive aims to improve the environmental performance of

batteries and accumulators, as well as the environmental performance of the

activities of economic operators involved in the life cycle of batteries and

accumulators. The Directive also sets limits to certain hazardous substances in

certain batteries and accumulators namely mercury, cadmium and lead.

Malta is to achieve the following minimum collection rates for waste portable

(a) 25 % by 26 September 2012;

(b) 45 % by 26 September 2016

based on the amount of portable batteries sales in the previous 2 years and the

Transitional arrangements could be laid down to postpone the targets if Member

States face difficulties in achieving these targets.

Furthermore, the Directive requires that facilities recycling waste batteries achieve

the following minimum recycling efficiencies:

a. recycling of 65 % by average weight of lead-acid batteries and accumulators,

including recycling of the lead content to the highest degree that is technically

feasible while avoiding excessive costs;

b. recycling of 75 % by average weight of nickel-cadmium batteries and

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

accumulators, including recycling of the cadmium content to the highest degree

that is technically feasible while avoiding excessive costs; and

c. recycling of 50 % by average weight of other waste batteries and accumulators.

Packaging and Packaging Waste

Waste Management

Packaging and Packaging waste

(Packaging and Packaging Waste)

Regulations, 2006

(Directive 94/62/EC )

(L.N. 277 of 2006)

Other applicable legislation:

Marking and identification

Commission Decision 97/129/EC on the identification system for packaging

Data and reporting

Directive 91/692/EEC standardizing and rationalizing reports

Commission Decision 97/622/EC on decisions relation to Directive

Commission Decision 2005/270/EC establishing the formats relating to the

Derogation for plastic crates and pallets from the heavy metal concentration

Commission Decision 1999/177/EC establishing the conditions for a

derogation for plastic crates and plastic pallets in relation to the heavy metal

concentration levels

Commission Decision 2009/292/EC establishing the conditions for a

derogation for plastic crates and plastic pallets in relation to the heavy metal

concentration levels

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Derogation for glass packaging from the heavy metal concentration limits

Commission Decision 2001/171/EC establishing the conditions for a

derogation for glass packaging in relation to the heavy metal concentration

levels (& corrections)

Derogation for glass packaging from the heavy metal concentration limits -

revision of deadline

Commission Decision 2006/340/EC amending Decision 2001/171/EC for the

purpose of prolonging the validity of the conditions for a derogation for glass

packaging in relation to the heavy metal concentration levels established in

Directive 94/62/EC

Harmonised standards for packaging

Commission communication 2005/C 44/13 in the framework of the

implementation of the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive

The Packaging and Packaging Waste regulations

The packaging and packaging waste directive transposed into national legislation

by L.N. 277 of 2006 aims primarily to reduce the volume of packaging waste and to

prevent the negative environmental impacts caused by improper disposal and

covers all the packaging placed on the market within the EU. The producer

responsibility approach results in accordance with this directive.

The following recycling and recovery targets were set.

Minimum overall recovery targets, overall recycling targets and material

specific recycling targets for the period 2004 – 2013

Recovery Recycling Recycling Recycling

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Notes:

(i) The overall recovery includes recovery and thermal treatment at waste thermal

treatment plants with energy recovery.

(ii) There is no maximum target for the overall recovery.

(iii) The maximum target for the overall recycling is 80%.

(iv) For the recycling targets for plastics, exclusively material that is recycled back

into plastics shall be counted.

End-of life vehicles

Waste Management

End-of life vehicles Directive

(End-of life vehicles) Regulations,

(Directive 2000/53/EC)

(L.N. 99 of 2004)

Other applicable legislation:

Commission Decision 2002/525/EC amending Annex II of Directive

2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life

Council Decision 2005/673/EC amending Annex II of Directive 2000/53/EC of

the European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life vehicles

Commission Decision 2008/689/EC amending Annex II of Directive

2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life

Commission Decision 2010/115/EU of 23 February 2010 amending Annex II

to Directive 2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on

end-of-life vehicles

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Commission Directive 2011/37/EU of 30 March 2011 amending Annex II to

Directive 2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-

of-life vehicles

Commission Decision 2005/63/EC amending Annex II of Directive

2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life

vehicles (spare parts)

Commission Decision 2005/438/EC amending Annex II to Directive

2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life

vehicles (spare parts)

Commission Decision 2003/138/EC establishing component and material

coding standards

Commission Decision 2001/753/EC concerning a questionnaire for Member

States reports on the implementation of Directive 2000/53/EC of the

European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life vehicles

Commission Decision 2002/151/EC on minimum requirements for the

certificate of destruction issued in accordance with Article 5(3) of

Directive 2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-

of-life vehicles

Commission Decision 2005/293/EC establishing detailed rules to monitor

compliance with the ELV targets

The End of Life Vehicles regulations

The provisions of the end-of life vehicles regulations aim at the prevention, reuse,

recycling and other forms of recovery of waste vehicles and their components. It

also aims to improve in the environmental performance of economic operators

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

involved in the life cycle of vehicles, especially those involved in the treatment of

an end-of life vehicle.

The regulations lay down provisions on the dismantling and recycling of waste

vehicles and set the following targets for reuse, recycling and recovery of waste

vehicles and their components:

No later than 1 January 2006, for all end-of life vehicles, the reuse and

recovery shall be increased to a minimum of 85 % by an average weight per

vehicle and year. Within the same time limit the reuse and recycling shall be

increased to a minimum of 80 % by an average weight per vehicle and year;

for vehicles produced before 1 January 1980, the Competent

Authority/Member State may lay down lower targets, but not lower than 75

% for reuse and recovery and not lower than 70 % for reuse and recycling.

No later than 1 January 2015, for all end-of life vehicles, the reuse and

recovery shall be increased to a minimum of 95 % by an average weight per

vehicle and year. Within the same time limit, the re-use and recycling shall

be increased to a minimum of 85 % by an average weight per vehicle and

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment

WEEE Directive

Waste Management (WEEE)

(Directive 2002/96/EC)

Regulations, 2004

(L.N. 63 of 2007)

to be repealed by

WEEE (recast) to be transposed by

WEEE Directive (recast)

14 February 2013

Directive 2012/19/EU

Other applicable legislation:

Commission Decision 2004/249/EC of 11 March 2004 concerning a

questionnaire on the implementation of the WEEE Directive

Commission Decision 2005/369/EC of 3 May 2005 laying down rules for

monitoring compliance of Member States and establishing data formats

Council Decision 2004/312/EC and Council Decision 2004/486/EC, as well as

acts related to the accession of new Member States, provide for some

derogations, limited in time, as concerns the targets set by Directive

2002/96/EC (WEEE)

The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment regulations

The Waste of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive set collection,

recycling and recovery targets for electrical and electronic equipment (EEE).

Together with the ROHS directive (2002/95/EC), it restricts the use of hazardous

substances in EEE. Currently, the WEEE Directive is in the process of its recast,

and is in its second reading.

The Directive is based on the principle of producer responsibility, which implies

that the costs of waste management are to be borne by the producer of the

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

product from which the waste came. It also obliges Member States to maintain a

registry of producers placing EEE on the market. The Directive also provides for

the creation of collection schemes where consumers return their used WEEE free

of charge. The objective of these schemes is to increase the recycling and/or re-

use of such products.

Member States shall ensure that, by 31 December 2006, producers meet the

following targets:

(a) a rate of separate collection of at least 4kg on average per inhabitant per year

of WEEE from private households.

(b) for WEEE falling under categories 1 and 10 of Annex IA,

the rate of recovery shall be increased to a minimum of 80 % by an average

weight per appliance, and

component, material and substance reuse and recycling shall be increased

to a minimum of 75 % by an average weight per appliance;

(c) for WEEE falling under categories 3 and 4 of Annex IA,

the rate of recovery shall be increased to a minimum of 75 % by an average

weight per appliance, and

component, material and substance reuse and recycling shall be increased

to a minimum of 65 % by an average weight per appliance;

(d) for WEEE falling under categories 2, 5, 6, 7 and 9 of Annex IA,

the rate of recovery shall be increased to a minimum of 70 % by an average

weight per appliance, and

component, material and substance reuse and recycling shall be increased

to a minimum of 50 % by an average weight per appliance;

(e) for gas discharge lamps, the rate of component, material and substance reuse

and recycling shall reach a minimum of 80 % by weight of the lamps.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Malta's derogation

In accordance with Council Decision 2004/486/EC granting Cyprus, Malta and

Poland certain temporary derogations from Directive 2002/96/EC on waste

electrical and electronic equipment, the above targets for Malta were postponed to

The WEEE recast has resulted in changes to the above targets together with the

collection rate of 4kg of WEEE per person every year. Through the WEEE recast

Malta is to achieve:

as from 14 August 2016, a collection rate that is lower than 45 % but higher

than 40 % of the average weight of EEE placed on the market in the three

preceding years; and

a collection rate of 65 % of the average weight of EEE placed on the market

in the three preceding years by not later than 14 August 2021.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Management of waste from Extractive Industries and Backfilling

Waste Management

(Management of waste from

Extractive Waste Directive

Extractive Industries and Backfilling)

(Directive 2006/21/EC)

Regulations, 2009

(L.N. 22 of 2009)

Other applicable legislation:

Commission Decision 2009/337/EC on the criteria for the classification of

waste facilities in accordance with Annex III

Commission Decision 2009/335/EC on the technical guidelines for the

establishment of the financial guarantee

Commission Decision 2009/360/EC completing the technical requirements

for waste characterisation

Commission Decision 2009/359/EC on the Definition of inert waste in

implementation of Article 22 (1)(f)

Commission Decision 2009/358/EC on the harmonisation, the regular

transmission of the information and the questionnaire referred to in

Articles 22(1) (a) and 18

Mining waste regulation

This Directive deals with waste coming from extraction and processing of mineral

resources and gives measures, procedures and guidance to prevent or reduce any

possible effects on the environment and any risks to human health. In Malta this

Directive was transposed by The Waste Management (Management of Waste from

Extractive Industries and Backfilling) Regulations, 2009 (L.N. 22 of 2009). These

Regulations address waste generated from the extraction of limestone from

quarries for the construction industry and the backfilling of the waste into spent

quarries for rehabilitation purposes.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Polychlorinated Terphenyls

(PCBs/PCTs)

Waste Management

(Polychlorinated Biphenyls and

PCB/PCT Directive

Polychlorinated Terphenyls)

Directive 96/59/EC

Regulations, 2002 (L.N. 166 of 2002)

PCB/PCT regulations

PCBs are regulated by Council Directive 96/59/EC of 16 September 1996 on the

disposal of polychlorinated biphenyls and polychlorinated terphenyls ("PCB

Directive"). The PCB Directive provides, inter alia, that Member States must take

the necessary measures to ensure that used PCBs are disposed of and PCBs and

equipment containing PCBs are decontaminated or disposed of. Equipment with

PCB volumes of more than 5 dm3 had to be decontaminated or disposed of by 31

December 2010 at the latest and a plan had to be prepared in this regards.

The national PCB/PCT Waste Management Plan was published in 2007 and was

intended for the decontamination and/or safe disposal of inventoried equipment

containing PCB/PCT and the PCB/PCT contained therein and for the collection

and subsequent disposal of equipment which is not subject to inventory. Limited

quantities of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) and polychlorinated terphenyls (PCT)

have been identified in the Maltese Islands. The volumes and storage locations of

equipment containing more than 5 dm3 of PCB/PCT contaminated oil became

known through an inventorisation process conducted in 2001. As there are no on

island facilities for the treatment and/or disposal of PCB/PCT, such waste had to

be exported for treatment. The last stock was exported to mainland Europe in

April 2010. In this context, there are no more PCB stocks in Malta.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Sewage Sludge

Sewage Sludge Directive

The Sludge (Use in Agriculture)

(Directive 86/278/EEC)

Regulations, 2001

(L.N. 212 of 2001)

Sewage sludge regulations

The purpose of this legislation is to regulate the use of sewage sludge in

agriculture in such a way as to prevent harmful effects on soil, vegetation,

animals and man, thereby encouraging the correct use of such sewage sludge.

The Regulation lays down limit values for concentrations of heavy metals in the

soil, in sludge and for the maximum annual quantities of heavy metals which

may be introduced into the soil. The use of sewage sludge is prohibited if the

concentration of one or more heavy metals in the soil exceeds the stipulated

The use of sludge is prohibited:

on grassland or forage crops if the grassland is to be grazed or the forage

crops to be harvested before a certain period has elapsed (this period, fixed

by the Member States, may not be less than three weeks);

on fruit and vegetable crops during the growing season, with the exception of

on ground intended for the cultivation of fruit and vegetable crops which are

normally in direct contact with the soil and normally eaten raw, for a period of

ten months preceding the harvest and during the harvest itself.

No spreading of sewage sludge on Maltese soils or any other application of

sludge on and in the soil is known to takes place at present.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

1.6. Guiding principles

The policy guiding principles set out in the 2001 Strategy remain valid and are being

reconfirmed hereunder. This is in addition to the overarching principle of sustainable

1.6.1. Sustainable development

According to the Brundtland Commission report of 1987, sustainable development is

"Development that meets the needs of the present generations without compromising

the ability of future generations to meet their own needs"

The principle of sustainable development implies that any development is sustainable

when positive SOCIAL, ECONOMIC and ENVIRONMENTAL outcomes are achieved.

Factors of sustainable development

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

The overarching principle of sustainable development was the backbone of this plan, by

addressing the social, economic and environmental impacts of the options proposed

towards improved waste management within the Maltese Islands.

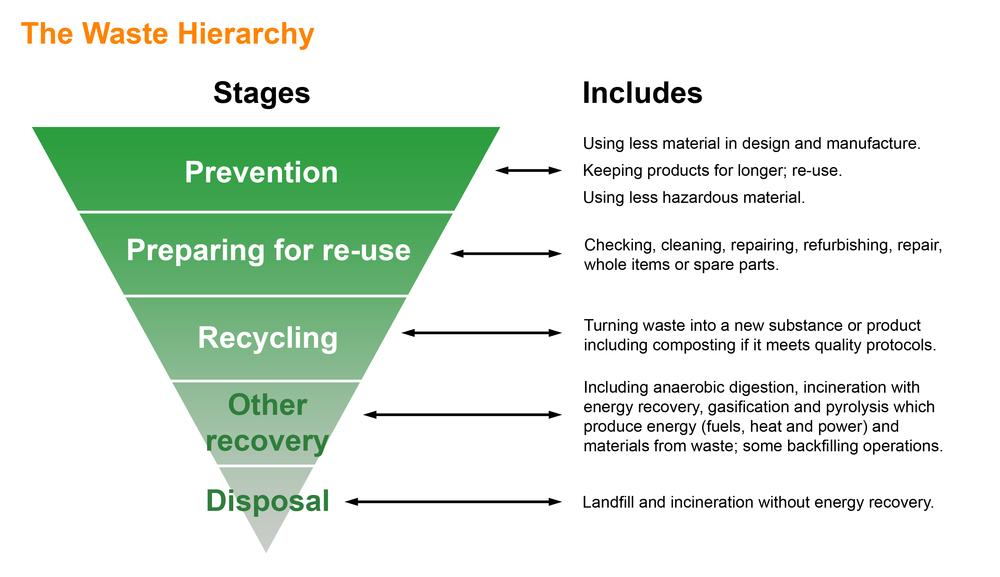

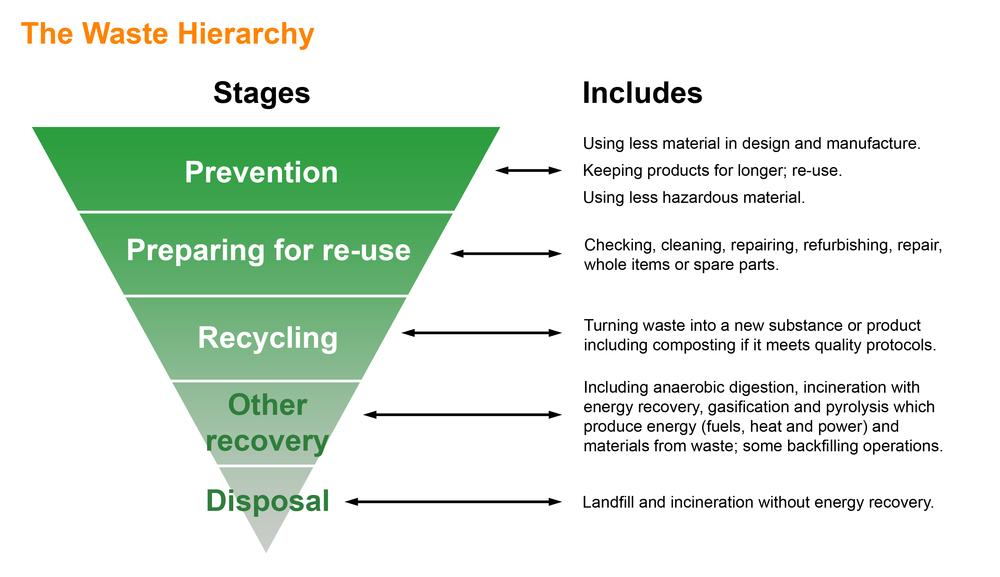

1.6.2. The waste hierarchy

The waste hierarchy is a concept laid down in the Waste Framework Directive which

ranks waste management options according to what its best for the environment.

Schedule 5 of the Waste Regulations gives waste prevention as the top priority. After

this, preparing for re-use, recycling and other recovery e.g. energy recovery are

preferred. Disposal is classified at the bottom of the hierarchy as it is the least preferred

waste management option.

Waste Prevention: includes those measures taken before a substance, material or a

product has become waste. These measures aim to reduce the quantity of waste, the

adverse impacts of the generated waste on the environment and human health or the

harmful substances in a product.

Preparing for re-use; includes checking, cleaning or repairing products that has

become waste so that they can be re-used without any other pre-processing.

Recycling: involves any recovery operation by which waste is reprocessed into

products, materials or substances for the original or other purposes.

Recovery: This involves any operation the principal result of which waste serving a

useful purpose by replacing other materials which would otherwise have been used to

fulfil a particular function, or waste being prepared to fulfil that function, in the plant or in

the wider economy.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

Disposal: any operation which is not recovery even where the operation has a

secondary consequence the reclamation of substances or energy.

Together with the life-cycle and ‘best available techniques approaches, this hierarchy

can significantly reduce negative impacts on the environment and human health. In

accordance with Article 4(2), laid down in the Waste Framework Directive, specific waste

streams may depart from the hierarchy, that is, may undergo recovery or disposal rather

than recycling, if it is proved by life-cycle thinking that the overall impacts of the

generation and management of such waste would be less than that for recycling or any

other higher ranked option.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

1.6.3. Subsidiarity and Proximity

This principle requires that waste should be treated or disposed of as close as possible

to the point at which it is generated. This creates a more responsible and hence

sustainable approach to the management of wastes by limiting the adverse

environmental effects from transporting waste over long distances. The distance that

waste should travel will vary according to the particular circumstances. Although it

should normally be practicable to dispose of municipal waste reasonably close to the

source of arisings, longer distances may be justified for other wastes, such as healthcare

wastes, for which specialised facilities may be required.

Malta is highly self-sufficient when it comes to waste disposal, with over 99% of the total

waste requiring disposal being disposed locally. Less than 1%, which due to its

hazardous nature, cannot be disposed locally, as there are no hazardous waste landfills,

is disposed of outside of Malta.

Data for year 2011

Total waste requiring disposal generated in Malta: 759,818 tonnes

Total waste disposed of in Malta: 757,612 tonnes (99.7%)

Total waste disposed of outside Malta: 2,206 tonnes (0.3%)

Data for year 20122

Total waste requiring disposal generated in Malta: 1,500,777 tonnes3

Total waste disposed of in Malta: 1,147,230 tonnes (99.8%)

Total waste disposed of outside Malta: 3,547 tonnes (0.2%)

2 Preliminary estimate as data for 2012 was still being compiled at the time of writing. 3 The increase is due to an increase in C&D waste only.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

The overall objective of the proximity principle is for waste to be disposed of within the

area of its generation. The proximity principle suggests that local solutions should be

sought wherever possible. However, this principle strongly advocated by the EU is of

more relevance to larger countries than island states, such as Malta. On account of the

quantities of waste generated and the size and land availability on the Maltese Islands it

is recognised that the provision of a large number of local waste management facilities

for the handling, treatment and safe disposal of waste close to where it arises may not

Malta, with an area of approximately 316km2 and a population of around 417,617, is the

smallest EU Member State both geographically and population-wise. Furthermore, Malta

has an inflow of approximately one million tourists a year. For such a small country, we

generate large volumes of waste. In 2010, 595.5kg of municipal waste were generated

per capita, which is 50.8kg less municipal waste per capita than in 2009 but still

relatively high in comparison with the EU average, which was 505kg per capita in 20104.

Waste is composed of a wide variety of materials. Construction and demolition waste

accounted for 68% of the total waste generated in Malta in 2011, while municipal solid

waste, which is composed of a variety of materials many of which are recyclable,

constituted only 22% of the total waste in that year. Although the generation of 1 million

tonnes of waste might seem to point towards the feasibility of the setting up of recycling

facilities, the amount of recyclable glass, plastics, paper/cardboard, metals collected

from all waste streams is relatively low (approximately 80,911 tonnes collected in 2011),

rendering it less economically viable to undertake recycling at a local scale.

A recent study carried out by the Malta National Statistics Office in 2011 provides a

breakdown of the composition of household waste, which is a good indicator for MSW

composition as municipal solid waste is composed of household waste and other similar

4 The Environment Report, Indicators 2010-2011, MEPA, 2011. The per capita figure was calculated by

dividing total municipal solid waste generated (including that generated by tourists) over the Maltese

population. The Maltese population does not include annual number of tourists visiting Malta.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

waste. This study suggests that mixed municipal waste consists of 40.7% recyclable

materials such as plastics, paper and cardboard, glass, metal and textiles. As at 2011,

this would translate to some 70,000 tonnes of recyclable materials in mixed municipal

waste which in addition to 15,000 tonnes of separately collected glass, plastic, metal,

paper and cardboard, the total potential recyclable materials generated by households

would total 85,000 tonnes.

Recyclable materials, including paper and cardboard, metals, glass and plastics

generated from the C&D and C&I sectors amounted to 10,775 and 55,625 tonnes

respectively in 2011. In this context, the generation of these waste materials does not

exceed 200,000 tonnes5. That is, the total waste paper/cardboard, metal, glass and

plastic generated in Malta as at 2011 does exceed 20% of the total waste generated.

Although EU waste legislation promotes principles of self-sufficiency and proximity, the

above explains Malta's existing waste management practices of landfil ing, disposal at

sea of inert wastes6 and recovery of dry recyclables for export towards recycling into

new products abroad. In this context, recycling Maltese waste comes at a high price as

the distances between Malta and mainland Europe and other countries make waste

transport relatively expensive.

In this context, Malta's specificities call for subsidiarity in those areas not governed by

EU legislation, that is, tailored made policies and measures not addressed at EU level

taking into consideration local challenges.

5 85,000 tonnes of recyclables in MSW, 55,625 tonnes in C&I and 10,775 tonnes in C&D – total 151,400

6 The following waste streams are disposed of at sea: inert geological material, inert C& D waste and

dredged material.

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

1.6.4. Polluter pays

The polluter pays-principle (PPP) is legally established in the EU in Article 191(2) of the

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which stipulates that:

"2. Union policy on the environment shall aim at a high level of protection taking into

account the diversity of situations in the various regions of the Union. It shall be based

on the precautionary principle and on the principles that preventive action should be

taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source and that the

polluter should pay."

This principle is enshrined iof the European Parliament and of

the Council of 21 April 2004 on environmental liability with regard to the prevention and

remedying of environmental damage (ELD), which establishes a framework based on

the polluter pays principle to prevent and remedy environmental damage. The Directive

defines "environmental damage" as damage to protected species and natural habitats,

damage to water and damage to soil. Operators carrying out dangerous activities listed

in Annex III of the Directive fall under strict liability (no need to proof fault). Such

activities include waste management operations, including the collection, transport,

recovery and disposal of waste and hazardous waste, including the supervision of such

operations and after-care of disposal sites.

Specifically on waste management, Article 14 of the Waste Framework Directive

(2008/98/EC) stipulates that in accordance with the polluter-pays principle (hereafter

referred to as PPP) the costs of waste management shall be borne by the:

original waste producer, or

current waste holder, or

previous waste holder.

Furthermore, the said article also established the ‘extended producer responsibility'

principle by stating that Member States may decide that the costs of waste management

are to be borne partly or wholly by the

producer of the product from which the waste came, and

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

distributors of such products may share these costs.

In order to better understand who is responsible for the costs of waste management in

accordance with Article 14 one is to refer to the definitions of "waste producer" and

"waste holder" laid down in Article 3 of the Waste Framework Directive. A waste

producer is defined as:

"anyone whose activities produce waste (original waste producer) or anyone who carries

out pre-processing, mixing or other operations resulting in a change in the nature or

composition of this waste;",

whereas a waste holder is defined as:

"the waste producer or the natural or legal person who is in possession of the waste;"

The current situation in Malta

Translating the PPP to waste management, the implementation of this principle implies

that producers of products and producers or holders of waste are liable to pay the full

costs for the management of the particular waste stream that they are generating. This

payment is usually implemented by means of a gate-fee charged at authorised waste

management facilities.

In fact, Article 10 of the Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC) states that:

"Member States shall take measures to ensure that all of the costs involved in the setting

up and operation of a landfill site, including as far as possible the cost of the financial

security or its equivalent referred to in Article 8(a)(iv), and the estimated costs of the

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

closure and after-care of the site for a period of at least 30 years shall be covered by the

price to be charged by the operator for the disposal of any type of waste in that site."

Malta has already introduced a gate fee at the Ghallis landfill to, as far as possible, be

representative of the actual cost of the operation itself.

Producers obliged under producer responsibility directives:

Directives that require the application of Producer Responsibility allow the Member

States to place the obligation of payment for the management of waste on the original

producer of a particular product rather than on the end consumer. There are four main

Directives that are implemented in Malta using this extended producer responsibility

principle. These are the Directives regulating, Packaging, Waste Electrical and

Electronic Equipment (WEEE), Batteries and Accumulators and End-of-life Vehicles

The PPP is well implemented in Malta from a legal perspective by means of the

enactment of legal notices that transpose the respective Directives. However it is

recognised that increased efforts, over and above those made to date, are required to

implement these legal provisions on the ground. Government also recognises that eco-

contribution legislation required review, and is currently being reviewed to take into

account the experiences registered by the operations of schemes in the packaging and

packaging waste sector. This review is at an advanced stage.

As regards to household and municipal solid waste, it is the Local Councils who manage

the costs for waste management through public funds allocated by Government. In this

context, such a system is indirectly funded by the general public through the income tax

regime. Local Councils set up agreements with contractors for the collection of solid

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

waste from their locality and also pay the gate fees stipulated by private waste facilities

and those stipulate by The Deposit of Wastes and Rubble (Fees) Regulations (L.N. 128

of 1997 as amended) for public facilities.

Currently it is not the producer of household waste who bears the direct cost for waste

collection and management but Local Councils. This with the exception of the collection

and management of dry recyclables which is funded by packaging producers and for

which, one may argue, that households are indirectly financing such an operation. In

this context, one is to determine whether local councils classify as the current holder of

the waste once the waste is collected from the kerb. The definition of waste holder laid

down in Article 3 of the Waste Framework Directive provides that s/he must be in

possession of the waste; however the Directive fails to define possession. There is no

legal definition in national waste regulations that defines possession of waste, nor do

they identify local councils as the legal possessor of waste once collected.

1.7. Situation analysis

1.7.1. Current waste facilities

Government through WasteServ Malta Limited (WSM) has throughout these years

developed basic infrastructure to deal with the various waste streams generated in the

Maltese Islands with the main emphasis on MSW. These public facilities are coupled

with additional infrastructure and services developed and operated by the private sector.

Details of existing public facilities which have been developed by WasteServ are as

Bring-in sites: Some 400 bring-in sites have been established in public areas and in

schools. These are intended for the deposit of at source segregated recyclables namely

plastic, paper, metal and glass. Recyclables collected through these facilities are

transported to the Materials Recovery Facility at Marsascala for further sorting, baling

and export. There are around another 430 bring-in sites managed by private operators,

making a total number of 830 bring-in sites across Malta and Gozo. In order to improve

Waste Management Plan for the Maltese Islands 2014 – 2020 – Final Document

upon separation rates achieved solely through bring-in-sites, producer responsibility

schemes have also accompanied this measure by a kerb side collection of dry

recyclables which has yielded a better return.

Civic amenity sites: WSM developed five civic amenity sites, four in Malta and one in

Gozo. These are supervised facilities where members of the public can bring and

discard a variety of household bulky waste. These sites cater for separate disposal of

domestic bulky waste such as tyres, refrigerators, electronic products, waste from DIY

activities and garden waste. The purpose of these centres is to establish service facilities

to optimise the collection of certain types of waste and increase the recovery of

secondary materials. These facilities are manned by a trained workforce and have

particular opening hours where people can enter with their car to deposit wastes

separately in specific containers.

Materials Recovery Facility, Sant Antnin Plant, Marsascala: This facility was

commissioned in February 2008 and is intended for the sorting of dry recyclable waste

recovered through the various initiatives currently implemented including the kerb-side

collection of recyclables, bring-in sites and other at source segregation initiatives. The

facility has a permitted capacity to treat 36,000 tonnes of incoming material. Products

from this facility are sold to registered brokers/authorised facilities for further

processing/export. Efforts to identify how the operations of this plant may be improved

have been published in a recent report7.

Mechanical Biological Treatment Plant, Sant Antnin Plant, Marsascala: This facility